The data you give away when using dating apps might seem like a small price to pay for the possibility of meeting someone new . But are you aware of what’s happening in the background? The systems by which data is collected, analysed, sold, traded and reused might be more complicated than you think.

Personal data is the goose that lays the golden egg in our modern economy. The industry of data brokers—the ones who buy and sell our data to third parties—is facilitated by the companies that organise our lives with operating systems, apps and hardware. Their business is to sell us gadgets and software, or provide a “free” service while forcing us to watch some ads. But this field is a growing and lucrative business model that in the case of the dating game can include information you probably originally intended to reach very few people. 1

Tinder, for example, collects and stores the sensitive data of its 50 million users worldwide. This includes: all chat conversations (time of day, length, and with whom), as well as information that is mandatory or that we decide to provide to enrich our profile, such as sexual preference, the age range we like to match with as well as the ethnic origin, educational level, political views, music and food tastes, pictures, videos and user location (or various locations). Tinder also knows which kind of people are interested in you.2 If you pay for any additional services or click on ads that appear in the app, you are also giving away your financial information, which is collected by tracking technologies. If you log in with your Facebook account, another chunk of data is taken from there, like your public profile, email address, “likes”, birthday, relationship interests, current city, photos, personal description, friend list, and information about your Facebook friends who might be common Facebook friends with other Tinder users (that’s why you may sometimes find that Facebook suggests friends who are people you’ve met in dating platforms).3

All the information you give dating apps is shared with Match Group, Inc. (the parent company of OurTime.com, BlackPeopleMeet.com, OkCupid, Twoo, POF, Meetic, LoveScout24, Match.com, ParPerfeito and Tinder), third-parties (a very big list of companies that are not listed in most of the Terms of Use and can change and grow according to the companies’ interests) and data brokers. The data is retained on the company servers for months, or in the case of Tinder, “as long as we need it for legitimate business purposes”. 4 In October 2011, an investigation run by Jonathan Mayer, a Ph.D. candidate in computer science at Stanford University, revealed that OkCupid was selling users’ information about drug and alcohol abuse. After the allegations, OKCupid said they ceased to do it.5

Now think about Grindr, a majority gay men dating app with 3.3 million users, that also includes trans, bisexual and queer people. The information requested, or that you deliver voluntarily to build up your profile, includes: HIV status or “last tested date”, unprotected sex choices and sexual preferences (top, bottom, etc), personal picture, display name, relationship status, ethnicity, age or date of birth, geo-location data (this feature has been turned off in order to protect users in some extremely homophobic countries like Russia 6, but other apps like Tinder or Happn still use it and may endanger the LGBTQ community7 ), email address, height, weight, social network links, “Looking For”, “About Me”, “Favorites”, “Blocks”, “Tribes” and more.

Regardless of whether a user quits or deletes the app, all this sensitive information could still be retained by Match Group and any affiliates they’ve already shared it with. If the data was released to partners, it may have been used as direct marketing or sold as a package of information to a data broker. Any information you provided to create your profile also exists in the form of a record held by a number of third parties. Paul-Oliver Dehaye, together with human rights lawyer Ravi Naik and journalist Judith Duportail, analysed the personal data from Duportail’s Tinder profile after asking the company to send it to her. They got 800 pages of all her activity in the app, as well as apps connected to her social media profiles such as Facebook) 8. According to Dehaye, the data collected by the app and shared with third parties is used for profiling and can affect your life when asking for a loan, applying for a job, a scholarship, or medical insurance. In the case of Grindr, or other LGBT apps like Her, Gayromeo, etc, it could also be very dangerous if you end up trapped in an airport in one of the 10 countries that punish homosexuality with a death sentence.

Data promiscuity via social networks

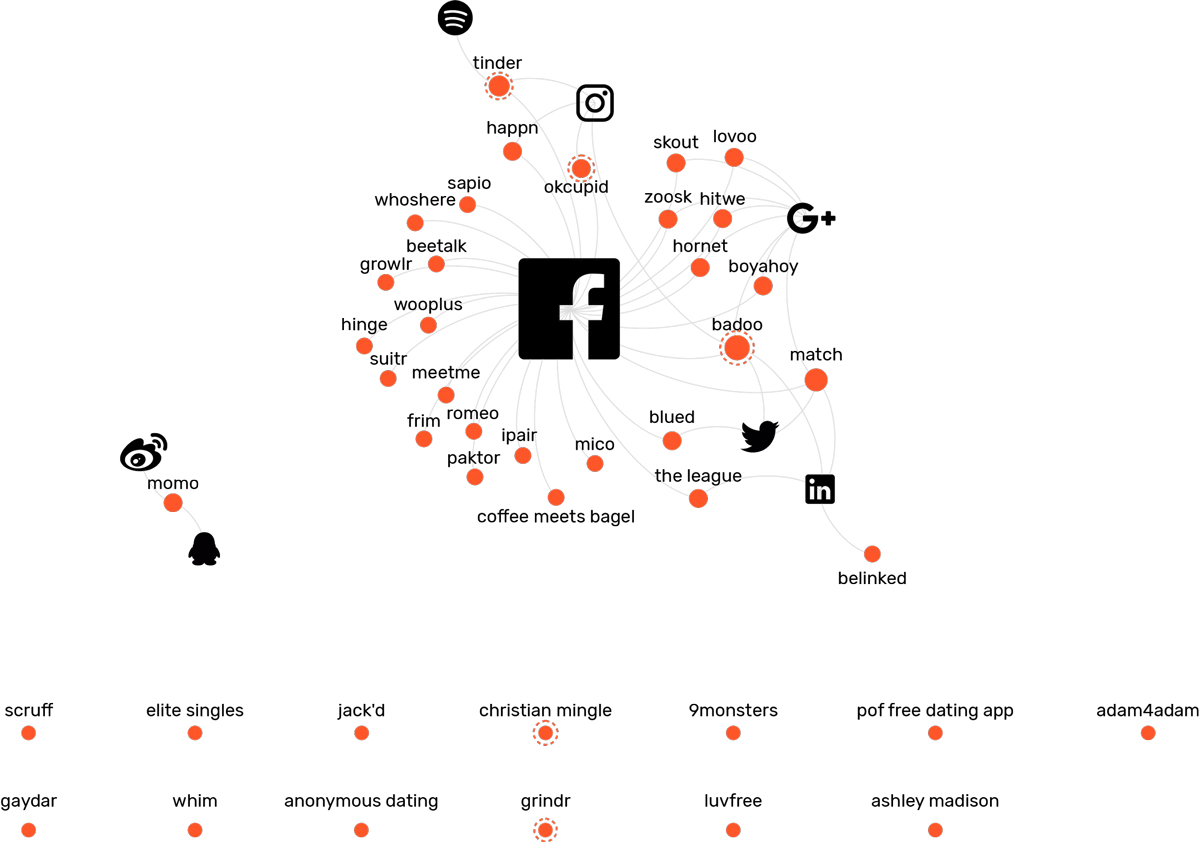

Facebook, which has 2 billion users, is the most ‘central’ social media platform, used by many of the dating apps to enable connections, as we can clearly see in the network map below. Aside from Facebook however, different dating apps allow connections to other social media platforms, specifically: LinkedIn (500 million users), Twitter (330 million users), Google+ (2.2 billion registered profiles), Instagram (800 million users) and Spotify (210 million users). Looking closely at this cluster of dating apps and social media platforms, we see that all the dating apps that connect to either Twitter, Google+, Instagram or Spotify also allow connections to Facebook. Only one dating app, Belinked, relies on connection to LinkedIn without also connecting to Facebook. In the bottom part of the map there are several dating apps – from Scruff to Elite Singles to Ashley Madison – that apparently do not connect to any social media platform at all. Instead, these dating apps seem to be quite isolated in the app ecology. To the left side of the map, there is a small cluster of Chinese dating apps, including Momo, that only connects to two Chinese social media platforms. Seeing that Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and other common platforms are not used in China, it makes sense that the Chinese dating app exists in an isolated ecology when it comes to social media connections.

Image by Andrea Benedetti, Beatrice Gobbo, Giacomo Flaim from Density Design

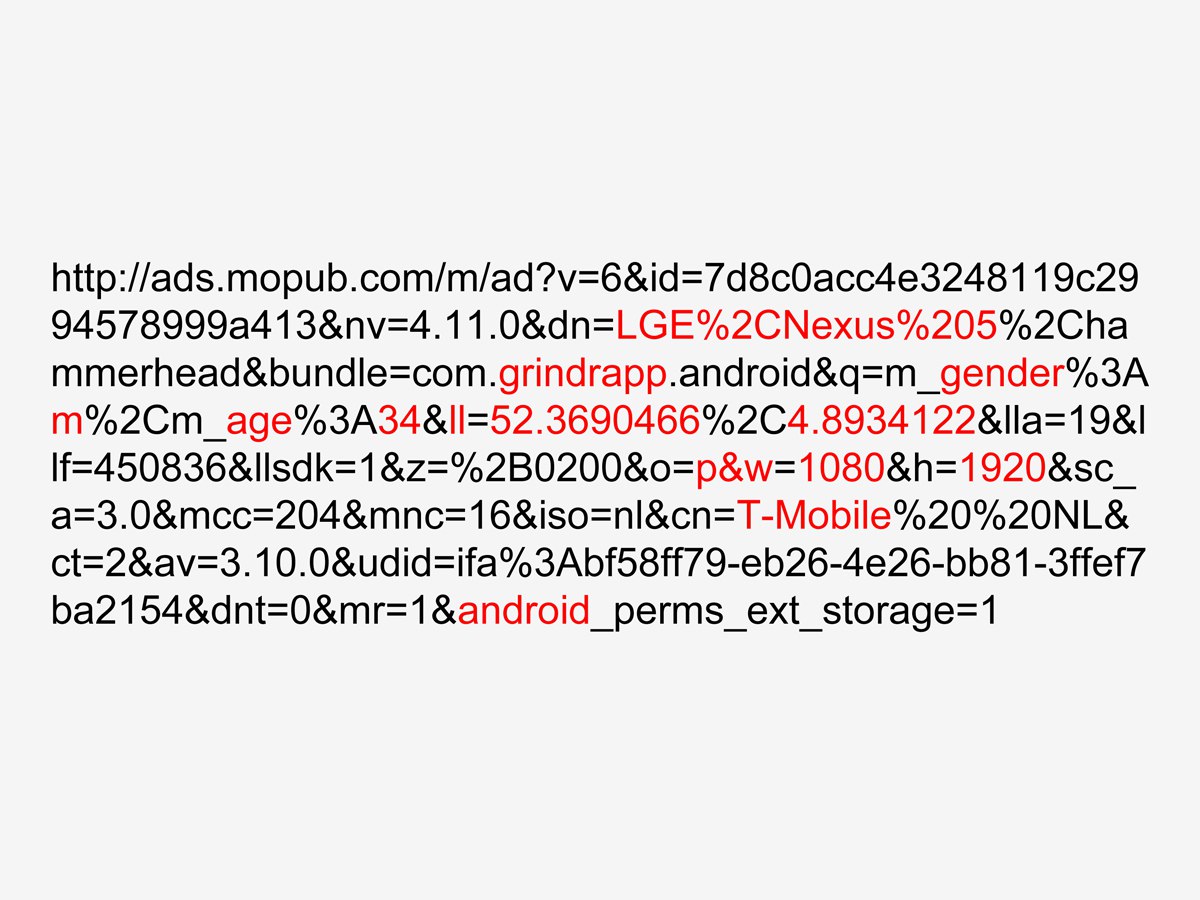

By viewing network traffic we can identify which third parties the dating app connects to. In addition, if the connection is insecure, we can also capture which data points are being shared. For example, Tinder makes all encrypted requests over HTTPS, except to serve images. This means that someone monitoring network traffic can see the photos of all the Tinder profiles someone is viewing on the network or even introduce false pictures to the user’s feed. The Grindr app communicates with 13 different advertising hostnames, some of which are unencrypted HTTP requests that include plain text user info such as GPS coordinates and type of phone. It is not easy to determine what accounts are fake or real, for users and app administrators alike. On the other hand, real name policies can discriminate against trans* individuals and decrease the privacy of people who want to remain anonymous to people they are not connecting with; not revealing their real names or last name is a common safety measure among users.10

In the example below, from an account created for testing purposes, you can see a typical unsecured HTTP connection to a third party advertiser. Here, the phone's brand and model, operating system, mobile carrier, device, screen dimensions, Grindr app, gender, age and gps coordinates, are all identifiable:

As part of an in-depth research project from which much of the information in this article was derived, Tactical Tech carried out 50 in-depth, qualitative interviews distributed around the Middle East and North Africa, Europe, the US and Latin American regions to users of dating apps from various genders, ages, and sexual orientations, some of which translated excerpts are presented below. In general, women and LGBT individuals were concerned about data being shared that could lead to a breach of personal information that the user didn’t want to expose:

“I have been creeped out on Happn even when I did my best to hide my identity to people, especially because there is a lot more information online that you can find about me if you know my last name or what I look like. I try to not reveal my last name or photos so users won’t find my articles that reveal my opinions about certain issues. However, one time, while being very conscious of not revealing any extra information, one guy was able to know my name, where I worked and the conferences at which I spoke , just by googling keywords of my first name and the college I went to. It turns out that there I am the only person with that name who graduated from that college.” (Lebanon, female, 34years-old, straight)

“Tinder connects to Facebook and Instagram, and it's often a little off-putting to see someone on there with mutual friends, especially if the mutual friends are ones to whom I'm not out. I'd be nervous to swipe right ("like") someone if we had mutual friends because I feel like it would risk them finding out about my sexuality or knowing too many details about my dating life. This isn't strictly related to social media, but Tinder also allows you to choose whether you are interested in men or women, and if you've chosen men it'll only show you other men who are interested in men. This lead to Tinder effectively "outing" a few men I knew in real life, since seeing them on Tinder meant they'd stated they were interested in men.” (Jordan, male, 21 years-old, gay)

“I found out that someone I blocked on OKCupid was still able to look at my profile.”(Germany, female, 37 years-old, straight)

Almost all respondents in the participating regions mentioned that Facebook was suggesting friends that were contacted via Whatsapp after a match. Actually, as Facebook owns Whatsapp, they do share by default a user’s telephone number, which enables Facebook to suggest mutual friends (but you can opt out in the privacy settings)11 Frequently, Facebook was suggesting people that were not even matched in the apps. This could lead to the outing of members of the LGBT community or making sexual behavior public that should not be known by co-workers, family or other people outside the apps.

“Some people that I haven´t even given a “like” on their picture added me on LinkedIn or Facebook.” (Argentina, female, 37 years-old, straight)

“Facebook is connected with Grindr and Whatsapp. If I´ve talked to someone on Grindr or Whatsapp and I don´t have this person on Facebook, it suggests me as a friend.” (Colombia, male, 35 years-old, bisexual)

What if my data is hacked?

“Life is short. Have an affair", was Ashley Madison’s claim to attract married people, or people in a relationship. The site claimed to grant privacy, and people believed it, or wanted to. But in November of 2016, a hacker attack revealed 33 million customers’ account details. As a result of the data breach, there were suicides and many suffered online harassment.12 Over a year after this data breach disaster, the most popular dating apps haven’t become much safer in general. An investigation carried out by Wired magazine revealed serious security problems in the most popular dating site services used in the UK.13 In 2016, two Danish researchers, Emil Kirkegaard and Julius Daugbjerg Bjerrekær, released the profile information of 70,000 OkCupid users without the permission of customers, or the company. Kirkegaard and Bjerrekær revealed sensitive information like sexual habits, politics, fidelity, feelings on homosexuality, location, demographics and user name, making it extremely possible to identify the person behind the profile.14 In Autumn of 2017, a group of researchers at the Moscow-based Kaspersky Lab studied the Android and iOS versions of Tinder, Bumble, OKCupid, Badoo, Mamba, Zoosk, Happn, WeChat and Paktor, and found that personal data such as email, name and location were sent with no encryption and could be easily accessed by cybercriminals.15

The risks and bad experiences that someone might encounter in the dating app environment is directly connected to what happens in the offline world. Sextortion, stalking, impersonation for revenge or extortion, rape and other sex crimes are problems where the rights of women and others in the LGBT community are not guaranteed.16 Some specific issues, such as unrequested charges on credit cards (in most cases managed by Google Pay) and “premium” user subscriptions not being able to be cancelled 17, are also common18.

Some hope on the horizon

Not everything is lost when it comes to the digital dating game. The idea of social trust, which is promoted in the app Gayromeo, allows users to confirm “trust” in other users through the feature “I Know This Person”. The feature enables people to highlight who they know personally and this is shown on the profile of the “trusted” person. This can be more relevant in countries where dating apps are used to entrap users of various taboo proclivites by either security forces (for example in Egypt), or right wing homophobic groups (for example in Russia). Although this could create additional problems related to social mapping, it could also solve problems like users creating fake profiles to target the gay community.

Last spring, Norway Consumer's Association let Tinder to change its terms and conditions, so now all files generated by Norwegian users will be deleted when the account is canceled (which differs from the general aforementioned rule of thumb of data being stored “as long as we need it for legitimate business purposes”); the terms and conditions are written in Norwegian in a simpler and shorter way, so that if needed, users will be entitled to solve disputes with Tinder in Norway19.

On July 2017, Tinder was valued at US$3 billion. It is estimated that its owner, Match Group, is worth US$4.8 billion, where Tinder represents more than 60% of the market20. It is a big business and companies should take users’ needs and safety into consideration. It is up to regulators – but also up to the public – to put pressure on companies and require a change in the game of “anything goes”. The “online privacy time is over”21 is announced by tech company directors, but when it comes to social media and dating apps, we have to go beyond the idea of if it is free, you are the product, and understand that if there are no users, there is no business.

Mitigation strategies

Historically dating companies have done very little in terms of user safety, which means that the care and protection of your data is in your hands. There is still no hard data about crimes linked to dating apps, and the majority of research on dating apps is being driven by the dating companies, instead of by governmental organizations tasked with prioritizing the safety of citizens.22 A year ago, a survey commissioned by Match.com among 2,000 users of dating apps found that 37% of them had been worried about their safety when dating somebody they met through one of these platforms. What is more concerning is that more than half of them didn’t report it to the company23.

What we can be assured of is that online dating is growing fast because it provides an alternative method of connecting, which can be more comfortable than the traditional bar flirting scenario. No more dealing with drunk people or waiting for men to make the first move; the chance to be clear from the start about what you expect from an encounter – a one night stand, just to meet new people, or a long-term relationship. Some respondents in our research said that one of their safety strategies is not to meet the person on the first date in their home:

“I have in the app that I work as a teacher but I don't say where I work.” (Jordan, female, 29 years-old, straight)

“I don’t answer questions about where I live or give away my Whatsapp number. I also tell friends where I’m going and keep them updated. I also don’t meet them near my home.” (Colombia, female, 40 years-old, straight)

“I meet people in a public space and never give my personal address on the first date.” (Brazil, male, 31 years-old, gay)

Nevertheless, as mentioned before, it is easy to get information on your location via the app24 . Just by activating the location, or choosing if you are looking for men or women, already reveals more to the contacts than the person is willing to tell. There are other good safety strategies mentioned by the users from the research, like for example telling friends where you are going, sending them notifications that everything is going well, and avoiding the connection with other apps through the profile.

“If I´m going to meet somebody new, I give all the info about this person to somebody I know and tell them how long they should wait to get some info or message from me. If I don´t contact them after this period there is a series of actions they will take.” (Colombia, female 36 years-old, bisexual)

“I don't give my social media account details, for hookups I don’t give my number, so the only contact is through the app. If I feel uncomfortable I can just block them on the app and they can't reach me in any way." (Italy, male, 23 years-old, gay)

“When I used it for threesomes we had a common profile as a couple that was fake. Nowadays I have my own profile but I don’t have any personal info in the description. I don’t connect with other platforms such as Instagram or Spotify either.” (Chile, male, 28 years-old, straight)

In order to enjoy the experience of dating apps and get the most out of it (without giving more of yourself than you want to give) here you’ll find a Decalogue of strategies that can be used to be safer when dating online25:

- If you create an account, don’t give all your personal information, don’t use your full name and don’t specify where you live or work

- Never give away your mobile phone number

- Never access a dating app through a public wifi. It can give anyone with little technical skills and enough bad intentions access to your data. If connecting is unavoidable, use a VPN

- Try not to connect with other accounts that may give away more personal information about you. If Facebook login is mandatory check your privacy settings and the information you’ve set as public. Do the same with Instagram

- Create an alternative email account for login

- It's recommended to use different pictures from the ones you use in your social networks; it’s not unusual to upload “mysterious pictures” which can guarantee you pseudo-anonymity

- Protect your mobile phone with passwords

- Install software that scans your phone for malware. Never open links sent by strangers because they can contain viruses or malware that can steal your data

- If the conversation is getting exciting, leave the chat and invite your crush to move to a safer platform like Wire (https://wire.com/en/), where you can create an account on the desktop without using your phone number, then later use the mobile version with your username. If you feel like sharing nude pictures, please visit Coding Rights’ Sexy Guide to Safer Nudes https://www.codingrights.org/safernudes/

- Before you go on a first date, tell a close friend who you are meeting and where. If you can, keep that person updated about how things are going.

There is no strategy that will give you total safety when using a dating app. However, this is also true for meeting people offline. If you want to play it safe, you don’t have to ditch the digital dating game completely, but knowing what’s at stake and how to protect yourself will allow you to have a much better date.

Article written by Raquel Rennó. We would like to thank Fieke Jensen, Joana Moll, Reem of 7iber, Nicole Shephard and Angela Precht. Part of this research for this article was produced at the DMI summer school at the UvA with the collaboration of Amanda Greene, Andrea Benedetti, Beatrice Gobbo, Cindy Krassen, Esther Weltevrede, Giacomo Flaim, Iulia Coanda, Laetitia Della Bianca, Lauren Teeling, Liping Liu, Mace Ojala, Mace Ojala, Philip Hutchison Barry, Rebekka Stoffel, Simon Boas, Sofie Thorsen.

Endnotes

4 https://www.gotinder.com/privacy

5 http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/blog/2011/10/tracking-trackers-where-everybody-knows-your-username

9 https://www.wired.com/story/tinder-lack-of-encryption-lets-strangers-spy-on-swipes/

10 https://antivigilancia.org/es/2016/09/colonialismo-censura-fin-del-anonimato/

12 http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-34044506

13 http://www.wired.co.uk/article/the-dating-apps-exposing-your-personal-life-to-hackers

14 https://www.vox.com/2016/5/12/11666116/70000-okcupid-users-data-release

15 https://securelist.com/dangerous-liaisons/82803/

16

https://www.genderit.org/feminist-talk/architectures-online-harassment-part-1

http://peru21.pe/actualidad/policia-capturo-anfitriona-acusada-pepear-8-jovenes-2255104

http://peru21.pe/redes-sociales/tinder-grinder-manhunt-cama-muerte-control-manos-2277199

https://actualidad.rt.com/actualidad/223937-inteligencia-brasil-usa-tinder-redes-arresta-jovenes

18 https://www.reclameaqui.com.br/busca/?q=tinder https://www.complaintsboard.com/complaints/tinder-unauthorized-credit-card-charges-c904202.html

19 https://www.forbrukertilsynet.no/eng-articles/tinder-changes-its-terms-and-conditions

21 https://www.cnbc.com/id/100354774

24 http://geoawesomeness.com/how-stalkers-can-use-dating-apps-to-track-your-current-location/

25https://gendersec.tacticaltech.org/wiki/index.php/Dating_platforms https://chupadados.codingrights.org/en/suruba-de-dados/

Published 15 February 2018