Ame Elliot critically reflects on political consequences of UX design.

User experience (UX) design is concerned with making technology easier and more pleasurable to use by creating interfaces that respond to user behaviour. The field has received increased attention from business and technology communities, in line with the rising economic power of smartphone apps. Funding has poured into improving apps' UX to simplify once complex online interactions, like registering for new services and making purchases. Beyond the business realm, UX design has become an important part of improving access to government services. Both the UK and US have new offices dedicated to upgrading their citizen-facing UX.

UX improvements that simplify complex actions are often described in tech jargon as “seamless” and “one-touch”, to convey how effectively they conceal background processes from the user. Seamlessness has benefits in making some services more accessible to a mass audience—for instance, opening a bank account. There are, however, situations where hiding complexity with seamlessness is harmful.

UX is the interface, the digital layer that obscures complex processes of data gathering and sharing. Design can thus obscure this clandestine collection of information, which can in turn be used to infringe individuals' privacy in dangerous ways. By the same token, UX design can shape a more ethical future, by revealing such violations and empowering users, giving them transparent access to information about how their data is being used—and abused.

This article takes the case of smartphone spyware to examine the disastrous consequences of seamlessness and the role of user design in it. Such software surreptitiously gathers information about how a device is used, and sends it to another party without the user's consent. In hiding complex system interactions from end users, the UX community actively contributes to making spyware difficult to detect. Even domestic abusers without the financial resources of powerful governments are able to install spyware to monitor their victims' phones.

That's why examining the role of UX design decisions in consumer-grade spyware is so important. First, it raises awareness of the capabilities of surveillance software. Second, it exposes opportunities to disrupt the socio-technical systems that make spyware possible. And finally, it helps identify new privacy-enhancing UX decisions.

Though consumer-grade spyware will always be difficult to overcome, UX design decisions can limit its reach and protect more people from increasing types of surveillance.

What is Spyware?

Historically, spyware has been developed by governments to monitor their enemies. Twentieth-century strategies of wiretapping landline phones and putting physical microphones in private spaces have given way to monitoring victims' cell phones. Trade shows, such as Intelligence Support Systems for Electronic Surveillance—also known as the Wiretappers' Ball—take place around the world to sell surveillance products to governments. Sales of this technology often skirt the law. According to a report by the Washington Post, for example, countries under US sanctions are not excluded from participating in the Wiretappers' Ball. In general, it is difficult to obtain information about the products and customers of companies that produce surveillance software for governments. Israel-based NSO Group is one such company—Forbes reported only basic information about its headquarters and Silicon Valley funding.

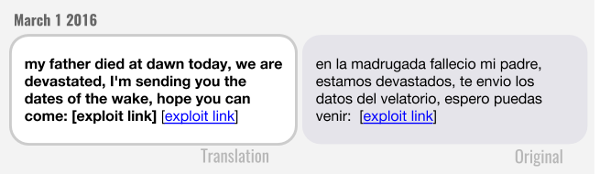

The University of Toronto's Citizen Lab reported that NSO spyware is being used beyond the context of governments' lawful intercept provision—that is, authorities legally collecting communications data for analysis or evidence. The report documents 21 cases of NSO spyware targeting human rights defenders, journalists and activists in the UAE, Mexico and Panama. In the case of Mexican journalists and lawyers who were targeted, victims phones were infected when they followed a link in a text message. Clicking the link silently installed spyware that not only took over their microphone and camera, but also collected messages, location and contacts.

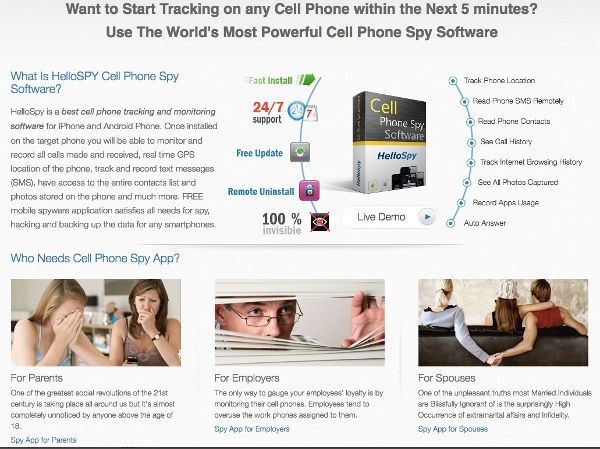

This type of spyware, capable of taking over a phone at distance, is extremely sophisticated and expensive, with Citizen Lab estimating prices of up to a million dollars. At a much lower price, companies such as HelloSpy sell spyware for US $170, making it accessible to a mass audience and allowing users to install it easily onto any phone in their possession. HelloSpy tracks the infected phone's location, reads all SMS messages, shares the contact list, accesses photos and captures its user's browsing history.

While detailing his experience being tracked with HelloSpy, security researcher and journalist Joseph Cox draws attention to how the software can be used as a tool for domestic abuse, through control of the victim's phone. Part of Vice's Motherboard series, When Spies Come Home, the investigation's focus on domestic violence is a notable exception in information security research, which tends to address surveillance by governments and corporations.

On its website, HelloSpy claims to have 850,000 customers. Although the software may be unsophisticated in comparison to the NSO Group's, its accessibility has potentially devastating consequences. The relatively low price point and ease of installation put this tool within reach of a broad swathe of people—well beyond the upper echelons of governments and powerful corporations. The democratisation of spyware means companies like HelloSpy can easily promote their spyware to anyone with $170 to spare. Instead of targeting political dissidents, HelloSpy targets three groups: parents wanting to spy on their children, employers wanting to spy on employees, and partners wanting to spy on each other.

UX Design Decisions to Limit Spyware

The app ecosystem has legal, economic, social and cultural dimensions that make it possible to install spyware. Information security has historically focused on preventing remote attacks with the kinds of technology showcased at the Wiretappers' Ball, rather than low-cost attacks by people like domestic abusers with access to their victims' phones. When unsophisticated but readily available spyware enters the market, domestic abusers have more powerful tools at their disposal to harm their victims.

There are, however, also specific UX design decisions that can limit the use of spyware by domestic abusers, by making it more difficult to install and easier to detect. UX design has three major opportunity areas for limiting spyware: rethinking authentication, communicating data use, and giving control panels more visibility.

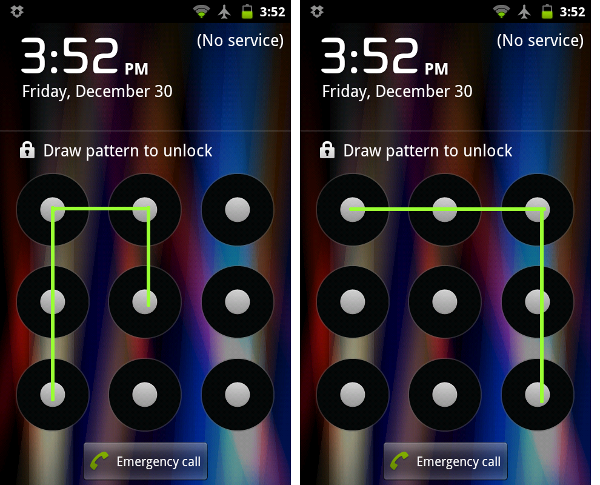

Authentication is the process of confirming your identity to a system, for example by entering a username and password. Although both Android and iPhones have screen lock capabilities, neither system is designed to handle threats such a domestic abuser knowing their victim's unlock code or forcing them to reveal it. While the banking industry has given much thought to ways in which victims might be forced to divulge their PIN to attackers, in the smartphone industry, such considerations remain peripheral. Relatively little time has been spent on the problem of how to thwart an in-person attack if the victim voluntarily unlocks their phone.

The secretive installation of HelloSpy on a victim's phone by a domestic attacker could be limited if the device contained hidden partitions protected by unique unlocking codes. For example, entering a fake unlock code, or none at all, would give the attacker access to only part of the phone.

Technically, Android already has the capabilities to partition a device, but there are significant UX barriers to configuring and accessing multiple parts of a phone. Making it simple to associate different unlock patterns or PINs with different sections could protect victims from spyware, so that even if an attacker had access to the phone, they could not access all its partitions. The UX could offer the opportunity to set different lock codes leading to different home screens.

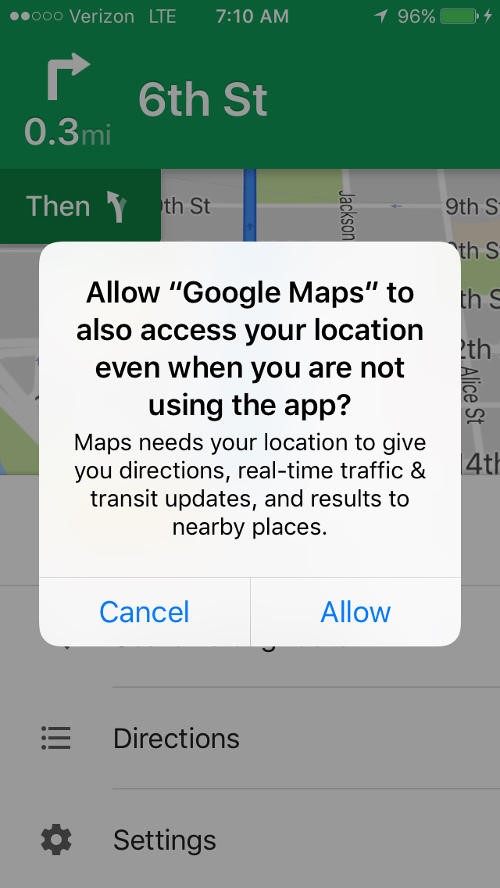

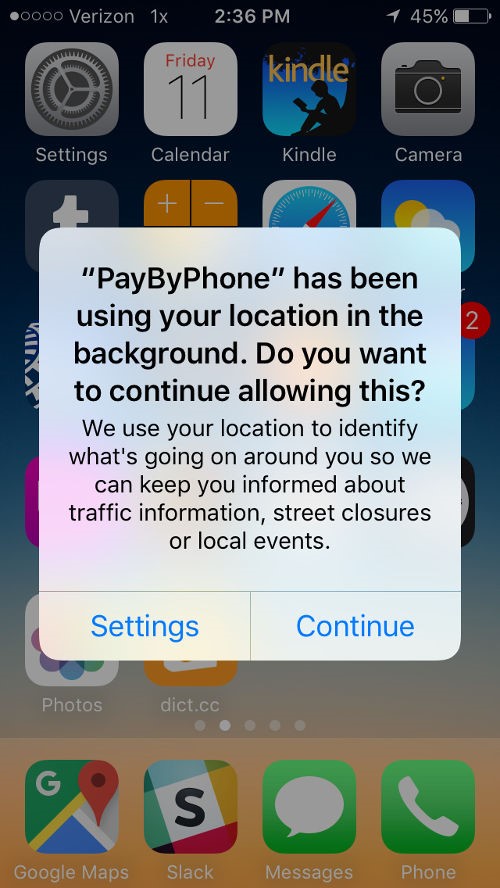

A second UX opportunity for limiting spyware is to more clearly communicate what data the phone is sharing with others. Spyware is insidious in part because it is silent, and the victim may not know that their phone is sharing information, such as their location. iPhones display location tracking information much more prominently than Android devices, with a flashing bar on the home screen naming apps that use the phone's location.

The next release of the iPhone operating system, iOS 11—scheduled for release at the end of 2017—will make information about which apps access location data even more prominent, and include background sharing. TechCrunch speculates this feature will change app development by “shaming apps that overzealously access location.”

Even if future releases of Android do not dedicate space on the home screen to displaying which apps track location, there are still opportunities to create new alerts that communicate when apps share data. For example, the current iPhone has three levels of location sharing for every app: never use location, use location while the app is active, and always use location. Alerts pop up when apps ask for additional permission—but more interestingly, if an app is constantly tracking a user's location, periodic alerts pop up telling users and giving them an opportunity to change the settings. Using an alert to resurface hidden behaviour is a powerful UX decision that to alerts victims of spyware that their location is being shared without their knowledge.

Alerts and home screen displays could be expanded to address more than location sharing. For example, letting people know when their photos or media are shared, or when messages are read. Instead of concealing these interactions in the name of seamlessness or ease of use, this kind of UX can let victims know that spyware has been installed on their phone, if they see an unfamiliar app is using their data.

As a protection measure, security expert Elle Armageddon recommends that if domestic violence victims do discover they are being tracked with spyware, that they use their phone as they normally would, since it could be dangerous to alert their abuser. Instead, Armageddon advises that victims initially seek opportunities to engage in private conversations and activities away from their phone.

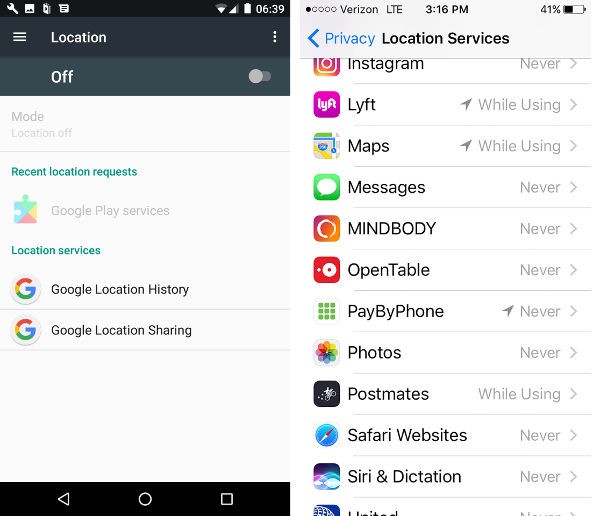

A third area for UX design to restrict the reach of spyware is to redesign settings and control panels to more clearly communicate what information apps share, and give people the opportunity to limit unwanted sharing. When iPhones send alerts that an app is using or requesting background access to location, the user gets the chance to view their privacy settings.

Settings are an underutilised educational opportunity. Potentially relevant information about location sharing is buried too deeply for the casual user to find. For example, on the iPhone's iOS 10.3.2, it takes seven clicks and considerable scrolling to get the setting that controls the display of location services icons on the home screen menu bar. Even though that feature is available, the UX decisions limit its use.

Bringing privacy-protecting settings and control panels into the foreground has the potential to empower people to protect their privacy and limit spyware.

How Can Spyware Be Stopped?

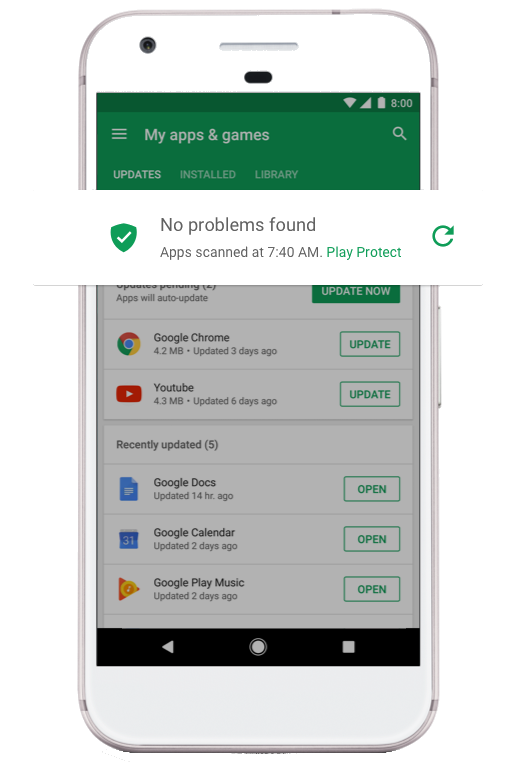

Google and Apple also work to keep spyware and other forms of malware out of their app stores. Google's Verify Apps program, for example, explicitly aims to keep spyware out, and its Play Store recently blocked spyware called Lipizzan— distributed as innocuous looking apps with names like Cleaner that infect a phone once installed.

Although admirable, the Verify Apps program does not stop spyware like HelloSpy for two reasons. First, the Verify App focuses on remote attacks and is not helpful if the attacker, for example a domestic abuser, has physical access to the victim's phone. Second, HelloSpy is not distributed through an app store.

The central feature of Google's Verify App program is called Google Play Protect, and requires clicking a button on the phone within the Play Store app to turn the service on or off. To disable anti-spyware protection, an attacker with the phone only needs to click the button to turn it off.

Another way to limit spyware would be to give greater attention to physical security, and create systems that are resistant to tampering by an attacker with access to the phone. There is a cultural blindspot in Silicon Valley that considers phones to be a personal rather than a shared resource, and many design decisions assume that people have total control over who accesses their phone. However, there are design opportunities, such as new forms of authentication, that could offer protection against spyware installed by someone with access to the phone.

These new UX design decisions could also limit the success of spyware like HelloSpy that is not distributed through app stores. According to Cox's report, HelloSpy sends customers an email with a link to download the app. It only takes a few seconds of access to someone's phone to turn off the warning, follow the link, and install the silent spyware.

UX Design Can Protect Privacy

UX design, both at an operating system level, such as iPhone location-tracking settings, and at the individual app level, holds the key to transparency into how data collection works in practice. Extending existing UX practices with privacy in mind can help nontechnical people understand how their phones can be used to surveil their behaviour, and build the awareness that is a precursor for greater privacy protections.

Although UX design alone is insufficient to stand up against spyware, it has an important role to play in making spyware more difficult for attackers to install and easier for victims to detect. The role of UX design in defending against spyware is even more critical now that spyware's potential targets have spread beyond political dissidents to potentially anyone with a suspicious partner. Considering the needs of domestic violence victims, we can begin creating a future where more people are better protected from surveillance. We can start by exposing how legitimate apps, such as retail or smart city applications, collect and share data. The key to making that information accessible to nontechnical users is through user experience design.

Ame Elliott is Design Director at nonprofit Simply Secure, where she cultivates a community of professional designers, developers, and researchers working on privacy, security, and ethical technology. Previously, Ame spent 15 years working in Silicon Valley, as Design Research Lead for IDEO San Francisco, and as a research scientist for Xerox PARC and Ricoh Innovations. She has delivered technology strategy for global clients including Acer, AT&T, Ericsson, Fuji-Xerox, Gannett, HP, and Samsung. Her design work has been included in the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum and recognized with awards from the AIGA, IDSA/IDEA, the Edison Awards, and the Webby Awards. She earned a Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley and a Bachelor of Environmental Design from the University Colorado, Boulder.