The Influence Industry Long List has been updated to include 500 companies available here.

In early 2017, when Tactical Tech began investigating how personal data is used in political campaigns, we knew it would be important to understand the companies, the people and the practices of the various organisations working with personal data for political influence. Who collects the data? Who uses it? How do they decide what to do with the information? Are there a few organisations engaged in data-driven campaigning or many? Do they work locally or across national borders? What are their motivations? What services are they offering and who owns them?

We started our research by examining a few news articles that profiled data brokers and data analytics companies. From there, we began a series of in-depth investigations into the context of these companies – the work they do, their outreach and how they fit into a landscape of other organisations and actors. We reviewed the websites and promotional materials they produced, we conducted open-ended interviews with some of their staff members, and we attended industry events. Our findings helped us map a digital campaigning industry whose breadth and depth far surpassed our expectations.

In the following series of posts, we will unpack our findings to reveal the partnerships we discovered, a few powerful consultants, and the ways political partisanship can affect political data. In documenting our efforts and methods, we also show how difficult it can be to understand the industry and how many revealing gaps there are in the publicly available information about it.

In 2018, Cambridge Analytica, the data mining and analytics company, dominated the news about political campaigning and data. But Cambridge Analytica is one actor among many. Our overview of organisations working with political data can also help map where their work fits within a broader industry, to understand which parts of their work were relatively normalised in modern political campaigning and which parts of their work were highly unusual and not representative of the broader personal data and political campaigning industry.

This context can also help us see the differences between Cambridge Analytica and other companies that have come under the spotlight for working with personal data in elections in the past. In 2007, for example, John Aristotle Phillips, the founder of a political data mining company called Aristotle, was profiled in depth by Vanity Fair about his “Orwellian database of voter records,” after having already come under scrutiny in 2000 when The New York Times examined Aristotle and the privacy issues of selling profiles. In 2014, Harris Media was in the public eye after Bloomberg published an article about its co-founder, Vincent Harris, called “The Man Who Invented the Republican Internet.” Harris founded the company in 2008, when he perceived a need for a Republican, data-driven campaigning company to rival the tools available to the Democratic party. Harris Media also received critical attention in 2017 after revelations that the company was running an attack campaign on behalf of President Uhuru Kenyatta in Kenya and working with the far-right German party AfD (Alternative für Deutschland).

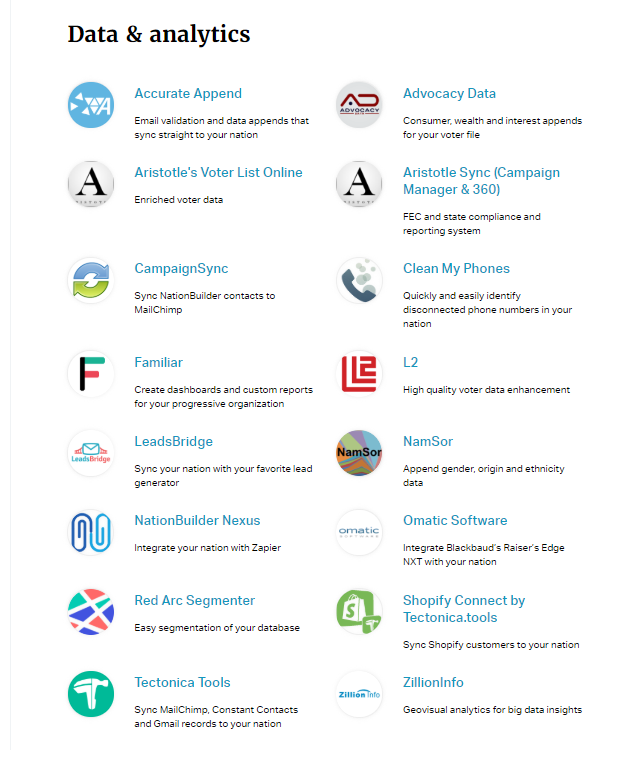

Our research began with these scattered investigations profiling a few companies. However, we discovered that the lack of consistent and regular reporting belied a richer and more complex web of organisations, which was easily found as soon as we started looking. From each entity, several threads would lead to others. For example, as shown below, the software platform NationBuilder’s website lists 16 other data companies they work with who either provide them with data, analytics or identity resolution practices. Within only a few weeks, we had a list of 60 agencies, companies or organisations who either sold data or relied on it for data-driven campaigning techniques, which they offered to political campaigns. At this point it was clear that within the larger data industry, there existed a distinct political data industry.

Since we began actively documenting this industry, and after examining job-listing websites, industry awards and events, and listings of organisations surrounding political campaigns, our list of industry actors has expanded to more than 300 organisations, and it is still growing. Most of the organisations we have identified so far are English-speaking and publish their work publicly or have been previously reported on. There are undoubtedly so many more to be discovered and documented. This beginning, however, is an indication of the breadth of the industry.

There are two features of these entities that are important to their impact on democratic processes. Firstly, most of them are for-profit companies, with the primary aim of generating, maintaining and growing revenue, a business model that inevitably guides their decisions – rather than traditional political metrics such as voter participation. Secondly, the organisations are, for the most part, hired for their expertise in data technologies rather than their knowledge or engagement in politics. Consequently, political campaigning is now often largely mediated by data-driven technology organisations.

In many cases, these organisations act as intermediaries, conduits or sub-contractors for campaigns. By collecting, aggregating and analysing data, these organisations represent voters’ profiles and opinions, which political campaigners in turn use to formulate their positions and design their communication strategies. Understanding these agencies and companies and how they work is essential to understanding how digital political campaigns work today.

The long list

The Influence Industry Long List has been updated to include 500 companies available here.

Who are they?

Current Total: 329

(See the full list here)

To date, Tactical Tech has identified more than 300 organisations around the world working with political parties through data-driven campaigning.

We included organisations on this list based on two criteria:

Firstly, they must have political clients. In some cases this is explicit on their websites, either because their work is explicitly aimed at political parties or because they list political parties as one of their clients. In other cases it was less obvious. Some do not openly list political clients but were found on lists of politically oriented organisations, including the nominees and winners of the Campaign Tech Awards and the Campaigns & Elections Political Pages. A few have been linked to political parties in news reports or based on our own investigations, though not explicitly on their websites. In this sense, this overview is a snapshot of what can be publicly found on the internet about the data industry that services political campaigning.

Secondly, their work must rely on techniques driven by personal data: either by collecting, selling or analysing data, or relying on data collection or analysis for their tools, techniques and strategies. We chose these categories based on the methods we have previously identified as relevant: using data as an asset, as intelligence or as influence. The section below shows how these criteria are mapped to the actors.

What do they do?

The organisations we identified here provide a wide spectrum of services, ranging from big tech companies providing off-the-shelf tools for hosting and analysing data, to communications specialists who design advertisements and websites for parties or candidates. They sometimes specialise in one method, but many engage in several techniques at once.

As an organisation focused on mapping the work of the Influence Industry, our aim is to have an open and constructive dialogue with the industry, to better understand their practices and to ensure a fuller and more accurate picture that aids understanding of the use of digital technologies and personal data in the political campaigning process. This is a crucial step in better understanding which practices within the industry are business as usual; which aspects create challenges for the democratic process and for voters; and what to expect from digital political campaigning in the future. Tactical Tech has interviewed staff members at a number of the organisations to ensure they had an opportunity to comment and that their opinions are included as part of this research.

We've categorised the list based on the following methods:

- Using data as an asset: data harvesting from various places including from collating database records, polling, ‘social listening’ and importantly, buying and selling this personal data.

Example: The data broker and analytics company i360, owned by the Koch brothers, gathers data from a variety of sources, including subscriptions, purchases and tracking cookies, for example. This data is used to identify and create detailed profiles of individuals, such as what parties they vote for, what websites they browse and what electronics they own. i360 sells lists of these profiles to political parties.

- Using data as intelligence: analytics, metrics, profiling, segmentation, as well as hosting data on databases such as customer relationship management systems.

Example: HaystaqDNA specialises in using data analysis to predict further information about individuals to add to their profiles. This information is usually about their potential political ideologies, such as their likelihood to support Donald Trump's views on the border wall with Mexico, Black Lives Matter or transgender bathroom use, amongst others.

- Using data as influence, campaigns: campaign strategy and planning, activism, fundraising, mobilisation*

Example: 270 strategies specialises in mobilising people. They use data to understand what types of communication are most effective at encouraging people to either turn out to vote or to invest their time and money in political campaigns such as recruiting volunteers for campaigns.

- Using data as influence, communications: public affairs, marketing, advertising*

Example: eXelate, owned by Nielsen, is a marketing company that specialises in using data for creating personalised advertisements that will reach people both in the right location and through a targeted channel (such as phone, TV or face to face).

This research relied on public information. Many organisations do not list their clients so we have identified and categorised them through secondary sources such as news reports or their inclusion on a list of political organisations, which is not always reliable or up-to-date. The gaps in the publicly available information is a significant indicator of both the lack of transparency the organisations have in declaring that they work for political parties and how difficult it is to track down current information. If you see anything you think is incorrect, or anything we have missed, please get in touch with ttc [at] tacticaltech.org. This is a living list and we will modify it as and when we find new or more up to date information.

*We have divided ‘Data as Influence’ into two categories: ‘campaigns’ and ‘communications’. This is a distinction based on how the organisations describe their own activities. ‘Communications’ are understood as advertising, marketing and communication strategies; while ‘Campaigns’ encompass politically focused activities such as mobilisation, fundraising and campaign strategies.

Where are they?

Some of the organisations on this list are small and work locally in a specific country or region; some are based in one country but have international clients; and some are large companies that have multiple offices worldwide. While we can generically say that there are various forms of organisations, due to a lack of publicly available information, it is difficult to pinpoint a specific set of locations where the organisations work. There are many possible reasons for this lack of clarity:

- It may be intentional: many agencies and companies don’t publicly list all the countries they work in or with whom they work. For example, in Tactical Tech’s interview with Thomas Peters, founder and CEO of uCampaign,1 he revealed that the company operates with or in some countries that are not represented on uCampaign's public client list, as they had signed contracts or otherwise had agreements not to talk about that work publicly.

- It can also be difficult to gain transparency due to the nature of this kind of work. There are companies who work as subsidiaries or sub-contractors to other companies. For example, the data broker Matchbox does not publicly state that they work with political parties, but they partnered with Aristotle, who in turn work with political parties. This makes it difficult to track which, if any, political clients benefit from Matchbox's work.

- Further, choosing whether we look at the company's headquarters, location of their offices or location of their clients changes the answer to ‘where they work’.

- Finally, our research is for the most part limited to publicly available and English-language-based information, so it represents only a particular portion of the industry. We plan to expand this list in the future to make it more international.

How long have they been around?

Some of the organisations we identified were founded in the last ten years, which coincides with a period in which the data industry has expanded exponentially. Some of them were established based on interest from a growing client base after Barack Obama’s successful 2008 presidential campaign was heralded for its effective use of data for targeting and mobilising voters. The company 270 Strategies for example, was launched “after years of leading key pieces of the Obama organisation.” We identified at least a dozen other companies or organisations founded or staffed by people who previously worked on the Obama campaign.

On the other end of the spectrum, some of the firms that are leveraging data are actually older companies adapting to new technologies. Experian, for example, is a large data firm that has sold data to the UK's Conservative and Labour parties. Its history can be traced back to a company called The Ramo-Wooldridge Corporation, founded in the US in 1953, which used technology in different commercial sectors, and began focusing on the credit industry in the late 1960s, when it bought the Credit Data Corporation. By the 1980s, they were already using names, addresses and public information to target specific demographic groups in the US. In 1996 the company was sold under the name Experian. The company continues to collect data using available resources for both credit scores and marketing techniques. This company too, is one of many, and there are numerous others in between.

Who do they work for?

There are various ways to categorise how organisations choose their clients: by location, by partisan identity, for purely political or commercial reasons, or if they're hired directly by parties or by other companies.

- Where are the clients? Organisations may work for local, national or international campaigns. Some work on all aspects and others choose only one.

- Is the organisation partisan? Some organisations choose to be partisan; others don’t. In our interview with Peters from uCampaign, for example, he said there was no option but to be partisan because “if you're a smaller company like us you, kind of, get black balled once you choose one side.”2

In another case, the French digital campaign strategy company Liegey Muller Pons declared in an 2017 interview in Le Monde, that they are non-partisan, to a point: “We work for all political parties except for the National Front. Economically, if we could sell our software to all candidates, even rivals, it would be ideal.”

- Do they work for commercial clients, too? Some organisations work for commercial clients and others are purely political. For example, when Tactical Tech interviewed Ken Strasma, co-founder and CEO of HaystaqDNA, he said: “After our success with the Obama campaign in 2008 is when this whole suite of technology really caught the attention of the press, and at that point, we were strictly political. But commercial clients started seeking us out.”3

The company then began taking on commercial clients. On the other hand, as seen above, Experian moved from being a commercial credit company to selling to political clients. Other organisations, like 270 Strategies, were founded to work solely on political causes.4

- Do they work directly for the client or for another company? Some companies don’t work for political parties but as contractors for other companies. For example, DataXpand is a company that provides services to other data and advertising companies. And there are companies who are owned by larger companies and report to them: for example, from the long list, Blue State Digital, Kanter and Xasis are all owned by WPP, a multinational advertising and marketing company working across many sectors.5

There are multiple ways to categorise the organisations to understand them: by the contents of their work, their clients or their staff. In the following series, we will publish more in-depth profiles of selected organisations from the list to provide more detail on each of the trends. The series will also examine the gaps in the list, including how online platforms interact with politics and the role of individual strategists. This investigation begins to map out the vast industry and to answer the questions on who collects data, how they decide what to collect and what they choose to do with it, as well as whom these organisations work with and the structure of their operations. Only by answering these questions can we understand the full impact – both the challenges and the opportunities – of the data industry on our political processes.

1 Telephone interview with Thomas Peters, uCampaign, 7 May 2017. ↩

2 Ibid. ↩

3 Telephone interview with Ken Strasma, HaystaqDNA. 2 May 2017. ↩

4 See ‘Our Story’ on the 270 strategy website at https://www.270strategies.com/who-we-are/ ↩

5 See full list of WPP companies at https://www.wpp.com/Contacts#tab-companies ↩

Amber Macintyre is a freelance researcher in campaigning and technology. She is currently working on the Our Data Our Selves project at Tactical Tech. The rest of the time she is carrying out research for her PhD at Royal Holloway, University of London, on the use of personal data by charities and NGOs.

Thank you to Stephanie Hankey for her ideas and feedback, Christy Lange for her attention to detail and editorial support and to Safa Ghnaim for posting it online. Thank you also to the Our Data Our Selves team, especially Varoon Bashyakarla, and our partners whose research helped populate this list.

Published November 29, 2018