The most commonly used social media platforms are powerful tools for communication, organisation, mobilisation, and access to information. Their business model is based on centralised data accumulation, processing and analysis. They can only be as good as the data given to them. A side effect of this unprecedented data aggregation that enables all the above mentioned benefits, is the creation of numerous opportunities for, surveillance, manipulation and cyber violence. The benefits and costs of using these platforms are far from balanced and very far from justified.

Data that we produce is often extremely personal - imagine the searches we do, question we ask, things we say or look at - these all generate data. But data is also when we do things, with whom we do them, in what context. All that brought together constitutes very powerful and insightful image of who we are and where we belong to, socially, culturally and politically.

Data is also something that can be easily amassed, duplicated, shared and manipulated. Often for profit or other benefits such as influence, control and harassment.

Social Media platforms have taken centre stage in the outreach and mobilisation efforts for civil society organisations (CSOs), grassroots groups, activists and concerned individuals1. In this piece we focus on four facets and actors of how the data genertated by users of social media platforms can be used.

Platforms and Personal Data: Concerns over privacy of both individual activists and entire networks, and over the collection and sharing of personal data. In addition to online censorship be it the take down of posts or suspension of accounts triggered by government requests or the judgement of the platform at hand.

Authorities and Personal Data: The targeting of activists and organisations based on what they share on social media; slander campaigns; legal action through obtaining personal information from the platforms via legal requests, and in some cases using force to obtain passwords to access information about the users and their social circles.

Adversaries and Personal Data: Through slander campaigns, the spread of false information, leaking personal photos and through attacks like doxxing which can have very serious ramifications.

Personal Context and Personal Data: Impacts on one's personal relations due to disaccords between the family or the employers and the political views or work of the HRD.

To start thinking more strategically about your data, and to respond to existing concerns, it is important to identify the threats and the vulnerabilities which could be different according to one's surroundings and the political context around. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) has a guide on Assessing your risks that is handy in mapping threats, the possible consequences and the available responses. Security in a Box, a project by Tactical Tech and Front Line Defenders, also has a chapter on how to asses your digital security risk

This guide from Security in a Box explains the basics of how to protect yourself and your data when using social networks

Good people can get hacked, too

Even if you trust the people you are sharing with, if you are using social media that creates user-accessible records (like when you can see past activity or message history), if someone else gains access to that person's device or account, the unauthorised person may look at messages and images that you thought would stay private

We are all in this together. The good part of this is that we have each other. The bad part of this is that it means that things that happen to one person, like having an account hacked, affects all of us. We can be responsible to ourselves and our communities by using strong passwords on our accounts and setting up 2 factor authentication, which is an additional level of protection that some services allow you to turn on. Talk to your friends and community about how this effects all of us and what they can do.

Having an account hacked can be an upsetting and scary experience. It can happen even if you are very responsible. Be kind to yourself and anyone else if an account is hacked and focus on recovering instead of blaming. If your account is hacked: try to regain access and immediately change your password and the password to anything else where you may have used the same password; and let people in your network know that your account was hacked and that information may have been exposed and that messages from your account may not have come from you.

Here are some links to resources that can help you protect your devices and protect you from hacking:

- Create and maintain a strong password

- Protect sensitive files on your computer

- Securing your devices against malware is key in protecting your data and the data of those you communicate with.

Protecting your device from physical threat:

In some countries, and in certain contexts, adversaries might resort to physical attacks to obtain data. This can range from theft, to police raids, and even physical violence to gain access to the devices. In this guide you can learn _how to protect your information from physical threats_

Identity: Who are you online vs. what you want others to know about you

The profiles created about us are not only based on the posts we publish or content we share or photos we upload. Let's start first by mapping your digital shadow, learning more about the digital traces you leave behind. This will help in assessing how much is out there about you, and give you an idea of where to start to have better control over your data.

The _Data Detox Kit_ is an 8-day data detox program. "In just half an hour or less per day, you'll be well on your way to a healthier and more in-control digital self."

The Zen Manual has an extensive section that explains how you can _map your digital traces_ and explains various strategies and steps you can do to regain control over your data.

Sharing Images, Videos and Documents on Social Media

When you use social media platforms, sometimes you share much more than you think. It is not only about the data you share, but it is also about the attached metadata. Metadata can be understood as a modern version of traditional book cataloguing. The small cards stacked in library drawers provide the title of the book, publication date, author(s) and location on the library shelves. Similarly in the digital sphere, a digital image may contain information about the camera that took the image, the date and time of the image, and often the geographic coordinates of where it was taken. Such multimedia-related metadata is also known as EXIF data, which stands for Exchangeable Image File Format. Exposing the Invisible has an extensive chapter on metadata part of the guide Decoding Data on how images and the metadata attached in them can pose a serious risk.

To better understand how to work with and around metadata, it is important to know in practical terms what is generally meant when metadata is mentioned. Below is a list of the metadata that may be stored along with different types of data:

Images

- The location (latitude and longitude coordinates) where the photo was taken if a GPS-enabled device, such as a smartphone, is used.

- Camera settings, such as ISO speed, shutter speed, focal length, aperture, white balance, lens type…etc. (please note that some cameras do include the location coordinates)

- Make and model of the camera or smartphone.

- Date and time the photo was taken.

- Name of the program used to edit the photo.

PDF files

- Author’s name, usually the name assigned when the program used to create the file was first installed.

- Version and name of the program used to create the file

- Title of the document

- Certain keywords

- Date and time of file creation / last modification

Text files

Depending on the program used to create the document, the data may include:

- The names of all the different authors

- Lines of text and comments that have been deleted in previous versions of the document

- Creation and modification dates.

Videos

Metadata in video files can be divided in two sections

- Automatically generated metadata: creation date, size, format, CODECS, duration, location.

- Manually added metadata: information about the footage, text transcriptions, tags, further information and notes to editors..etc.

- Recommended reading: A thorough overview on video metadata and working with it from WITNESS.

Audio

Audio metadata is similar to video but more widely used especially to register property of the file. In addition to that it can include:

Creation date, size, format, CODECS, duration and a set of manually added data like tags, artist information, art work, comments, track number on albums, genre..etc.

Communication

Metadata in communication depends on the type of communication used (i.e. email, mobile phone, smartphone..etc). But in general it can reveal the following (if no tools to hide the metadata are used):

- Ids of the sender and the receiver

- Date and time of communication

- Location

- Mode of communication..etc

The Zen Manual recommends the following general steps that could be very helpful to adapt as a general privacy-protecting practice.

You can switch off the GPS tracker in your phone or camera. You can also limit various apps’ access to your location data, contacts, and pictures in your phone settings. You can also read more about alternative tools that offer encrypted mobile communication on mobiles such as Signal.

When registering a device or software such as Microsoft Office, Libre Office, Adobe Acrobat and others, you don't need to use your real name. This prevents the metadata created when using this device or software from being connected to your name.

When publishing content online you can change files from ones that contain a lot of metadata (such as .doc and .jpeg) to ones that use less metadata (such as .txt and .png), or you can use plain text.

You can use tools to remove metadata from certain files. For images there is Metanull for Windows.

For PDFs, Windows or MAC OSX users can use programs such as Adobe Acrobat XI Pro (for which a trial version is available). GNU/Linux users can use PDF MOD, a free and open source tool. (Note: this tool doesn’t remove the creation or modification timestamp, and it also doesn’t remove the information about the type of device used to create the PDF.) You can also review MAT (Metadata Anonymisation Toolkit), a toolbox to anonymise/remove metadata used by TAILS for instance. For a full guide to removing metadata from different file formats, see Tactical Tech's resource on how to remove metadata.

In the guide Decoding Data from Exposing the Invisible you can deepen your knowledge about working with metadata, controlling what shows and removing it from where you don't want to be.

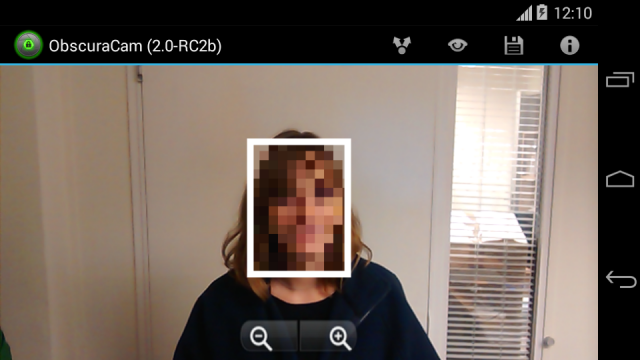

Alternatives for Sharing Images

ObscuraCam from the Guardian Project is a photo and video app for Android that keeps certain information private. It allows you to pixelate, redact (blackout) or protect with funny nose and glasses. You can also invert pixelate, so that only the person you select is visible, and no one in the background can be recognised. This app will also remove all identifying data stored in photos including GPS location data and phone make & model. You can save the protected photo back to the Gallery, or share it directly to Facebook, Twitter or any other “Share” enabled app.

The Double Life of a Human Rights Defender: Anonymity on Social Media

Threats from family and professional circles are quite context specific and their impacts vary. The restrictions in the country due to repressive laws, or social impositions, or the beliefs held in the social or professional networks of the activist can play an important role.

In certain contexts the exposure of an activist's work to family members can result in tension and alarming consequences. In the research paper "Women's Bodies on Digital Battlefields" published by Tactical Tech, and based on the analysis of 14 pro-choice websites and 55 testimonies from activists, technologists, and volunteers; the internet was named as a strategic tool in continuing to provide support for women when face to face outreach and support is too risky. But also concerns were raised regarding the possible threats.

There are two factors which prompt activists’ attention to perceived risks. First, adversaries might intercept confidential data about pro-choice activists and the women they support, which can lead to criminalisation or ideological persecution.

Second, the unexpected consequences of trails. The information that is associated with our digital activities can become, for data brokers and governments, pathways to surveillance, or ’data—veillance’, and targeted discrimination. This means activists need to be careful about the data traces they leave while organising because metadata that may seem harmless today, might put them at risk for exposure under future legislation, regulation, or business models.

Regarding attacks, we can see that in countries where the right to abortion is restricted or completely forbidden, pro-choice activists face a wide array of threats and attacks from governments and fundamentalist groups. Some attacks take place without sophisticated technical skills and only require coordinated actions among people; this is how pro-choice activists face online harassment, smear campaigns, reporting of their contents and profiles, doxxing, stealing of social media accounts, identity theft, and censoring websites.

Certain kinds of attacks require more technical or human infrastructure: malware infection and the use of targeted spyware, disinformation tactics in internet search engines, and cloning online services to redirect women seeking information about safe abortion towards anti—choice materials.

Considering how potential online identities can improve your safety (and the safety of those connected to you personally and professionally), is crucial to accurately assessing your risks, as well as the technical skills and abilities you would need to use various types of online identities safely. You also need to think about which kind of identity you’d use in a given context. The following questions illustrate elements you should be considering when evaluating alternate online identities:

- Would my safety, job or livelihood be at risk if my real identity were known?

- Would my mental health or stability be affected if my participation in certain activities were known?

- Would my family or other loved ones be harmed in any way if my real identity became known?

- Am I able and willing to maintain separate identities safely?

But having anonymity on social media is not always a binary question of anonymous vs. exposed. There are various options that could be suitable for people according to their context. The Zen Manual has a good overview of the various options with risks and efforts involved:

Real name

Risk: Using your "real world" identity online means you are easily identifiable by family members, colleagues, and others, and your activities can be linked back to your identity.

Reputation: Others can easily identify you, thus gaining reputation and trust is easier.

Effort: It requires little effort.

Anonymity

Risk: It can be beneficial at times, but also be very difficult to maintain. Choose this option carefully.

Reputation: There are few opportunities to network with others thus to gain trust and reputation.

Effort: Intensive as it requires considerable caution and knowledge. It will probably require the use of anonymisation tools (for example Tor or TAILS)

Pseudonymity

Risk: Pseudonyms could be linked to your real world identity.

Reputation: A persistent pseudonym that others can use to identify you across platforms is a good way to gain reputation and trust.

Effort: Maintenance requires some effort, particularly if you are also using your real name elsewhere.

Collective Identity

Risk: Possible exposure of your real world identity by other people's actions in the group.

Reputation: While not a way to gain individual reputation, you can still benefit from the reputation of the collective.

Effort: Although secure communications are still important, it requires less effort than anonymity.

Logistics of Social Media

Though social media platforms have multiple and varied uses for activists and HRDs. The most common reasons behind the use of those platforms are sharing information, creating events, coordinating and organising, and engaging in discussion.

Your identity

It is worth considering using a collective profile/identity if you want to protect your privacy. Sharing the same account with different people under a pseudonym could be a good way to confuse the algorithm and create noise in the data collected about you. Everyone has a different pattern and habits of their own that can be used to identify them. Sharing a profile is a good way to obfuscate those patterns.

Sharing information with a wider public

If your reason to use social media is to share information with a wider public, consider the following:

Do you want everyone to see what you share? If not, you can use Friend Lists if you are on Facebook. Lists allows you to curate who can see what but this doesn't stop Facebook from accessing and storing your data.

Once you are logged in to your Facebook account, you will find "Friend Lists" under the left hand column.

- Click Friend Lists under Explore on the left side of your News Feed.

- Click Create List.

- Enter a name for your list and the names you'd like to add. You can add or remove contacts from your lists at any time.

- Click Create.

Be creative in the names you give your groups. Avoid using “Family” for your family members, and “Work” for work contacts. Also avoid using Facebook's "smart lists" which are based on data collected from your profile. Categories include your hometown, city of residence, family..etc. These lists expose your contacts even if they have chosen not to share their information with Facebook. For example, if you add someone to the _smart list under your city, and this person hasn't included this information in their profile; Facebook will ask them to add the city on their profile and will also profile them under it.

From now on, when you publish something, you can have much more control on who can see your posts. But it is important to remember that if any of the people on your lists have their accounts or devices compromised, what you share will also be visible to them. Using social media is a series of trade-offs, and you should always assess the pros and cons accordingly.

Activist Alternatives to Facebook

There are various options to substitute Facebook, but one of the common things you'd hear when you suggest those alternatives is that "not everyone is on them". But not everyone was on Facebook when it first started and it could be worthwhile to invest in inviting contacts within your network to join you on one of the alternative platforms - even if it was only for the sake of the activist or sensitive work you are doing while maintaining a Facebook account for personal matters. In general it is important to be strategic about what tool you use for what means. Using different platforms for various tasks will help decentralise the possible collection of your personal data.

Platforms like Diaspora are open-source and oriented towards user-control. They are decentralised, meaning no single company can own your data nor the data of all the users. No centralised registry on all users can be sold, and users can come together to set their own 'pods' on the platform.

Twitter has much less privacy settings than Facebook, but it is still easier to protect one's privacy there. With using a trusted VPN, being careful about what personal information you share about yourself when creating your account and during use, and by avoiding conversations with personal contacts sharing information that can be easily tracked back to you or your network, it is easier to protect your privacy.

But if you are a politically engaged individual or part of a network that is doing sensitive work, surveillance could be a serious threat especially in countries of risk. For example, hashtags and those who use them are vulnerable to surveillance and social graphing. You can learn more about that in Disclosures of a Hashtag

Activist Alternatives to Twitter

Mastodon is the Twitter-alternative that echoes Diaspora. It is open-source, decentralised, and allows users to create their own 'communities' that can interact among each other or not.

Creating events & publicising them

Many people say they are on Facebook to know about Events and many groups find this tool helpful to organise gatherings and invite people. Many find it a helpful way to track attendance and share updates with participants. But the way you as an organiser can have all this data about your attendees, Facebook and adversaries who might access your event will be able to collect all this data. If you are planning a sensitive event, or a political gathering that might attract adversaries it is better to refrain from using Facebook.

If your objective outweighs Facebook knowing about the events and who is attending it, consider using private events that are invite-only making sure to mark that only the host can issue invitations.

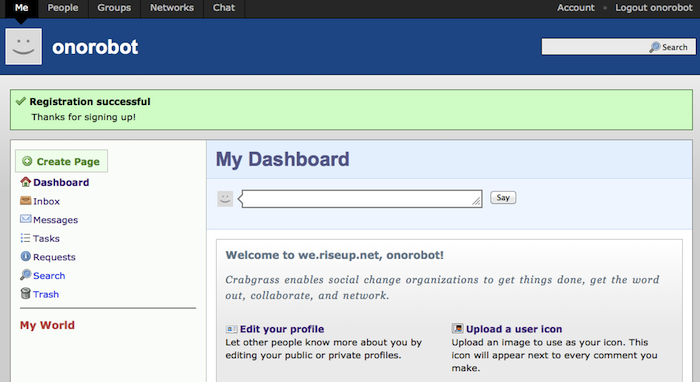

As an alternative, consider using "traditional" ways like posters, emails, flyers, and text message invites. If you are a group or an activist who frequently organises events for a closed group or a determined network, consider investing the time in starting an account on Crabgrass . Crabgrass is a secure web-based organising tool specifically designed for activists. It can function as a social platform where you can discuss with other people, as well as organising tasks in private groups. This guide will give an overview of the options available when using Crabgrass. This is a social networking tool tailored specifically to meet the needs of bottom-up grassroot organising as it has the ability to collaborate online, share files, tasks and projects.

Groups

Many grassroot groups and activist networks use Facebook groups to discuss, pool links and information, and organise upcoming events. This is especially helpful when meeting face-to-face is not easy or possible. But though Facebook groups can be "closed" it is still a question of wanting your data and all the information shared by your contacts stored on the servers of a for-profit corporation. ُ

For this, Crabgrass is a very good alternative. It allows everything a Facebook group allows you to do with the additional layer of privacy and security.

Messenger

Facebook Messenger is commonly used to communicate and chat with contacts and groups. Years of research into privacy and surveillance on Facebook, in addition to the recent news around Cambridge Analytica and Facebook's harvesting of personal data including phone records and text message metadata have raised further concerns over the security and privacy of the Messenger app.

Messenger is the easiest Facebook service to replace, there exists a variety of secure, open-source, encrypted and efficient alternatives. Unlike other services provided by Facbeook, Messenger actually has multiple alternatives that are competition worthy. You can consider Signal , Riot , and Jitsi .

_ This article was written and compiled by Leil-Zahra Mortada and Rose Regina Lawrence with contributions from Marek Tuszynski _

Shrinking Civil Space: A Digital Perspective

Data and Activism

Last-Minute GDPR Checklist for Civil Society Organisations

Data Baggage, Travel and Activism

What the Facebook?! To Leave or not to Leave

I Just Can't Quit You! Your Privacy Guide to Facebook

Will You Be Attending? How Event Apps Collect Your Data

Applying for a Visa

Booking Flights: Our Data Flies with Us

What's in Your Police File?