Booking a flight is so common nowadays that for many of us it has become an almost automated series of actions: go online, compare prices, decide on an airline, read some reviews, choose a good connection and a decent travel time. Fill in the form. Choose our seat. Pay. Print the ticket or add it to our smartphone.

But when privacy concerns are thrown into the mix, things can get turbulent. No matter where we purchase a ticket (whether from a travel agency, an online travel agency like Kayak, or directly from an airline) all these companies request a lot of our personal data. Though that may seem like normal procedure, it is less straightforward when you consider that the data we give up travels between companies, governments and hidden third-parties. It's even more troubling when this data becomes a factor in our ability to travel or not to travel; or worse, when it is used to profile entire communities or movements.

Flight-booking data is the cornerstone of an intricate migration and counter-terrorism security system put in place by many countries, either independently or through bilateral or multilateral agreements between governments. In an era of mass surveillance, this raises serious questions about how these systems are being applied to the general population – in particular, if they are targeting groups and communities that have historically been subjected to profiling or have recently entered the political spotlight, such as people from Muslim-majority countries. In addition, journalists, politically-engaged artists and Human Rights Defenders are similarly at risk.

PNR: The Dataset that Everyone Wants

Every time you book a flight, you generate personal data that is ripe for harvesting: information like the details on an ID card, your address, your passport information and your travel itinerary, as well as your frequent-flyer number, method of payment and travel preferences (dietary restrictions, mobility restrictions, etc.). All that data becomes part of a registry, in the form of a Passenger Name Record (PNR) – a generic name given to records created by aircraft operators or their authorised agents for each journey booked by or on behalf of any passenger.

When we book a flight or travel itinerary, the travel agent or booking website creates our PNR. Most airlines or travel agents choose to host their PNR databases on a specialised computer reservation system (CRS) or a Global Distribution System (GDS), which coordinates the information from all the travel agents and airlines worldwide, to avoid things like duplicated flight reservations. This means that CRSs/GDSs centralise and store vast amounts of data about travellers. Though we are focusing on air travel here, it is important to note that the PNR is not only flight-related. It can also include other services such as car rentals, hotel reservations and train trips.

Originally, PNRs were used internally by transportation services for their own commercial and operational purposes. But after the 9/11 attacks, the US government began demanding passengers' PNR data before an aircraft's arrival at a port of entry in the country. Several other countries quickly followed suit, including the EU nations, Canada, Australia, Mexico, Japan, New Zealand and Argentina, among others. In the EU, the PNR directive was approved in 2016, obliging all airlines to collect their passengers' data and hand it over to the EU member states.

“Perhaps the best way to conceptualize PNR data is as 'metadata about the movements of our bodies.' As such, PNR data can be even more intimate than the metadata about the movement of our messages that governments can obtain through Internet or telephone surveillance, or the metadata about the movements of our money obtained from banks and other financial institutions.” Edward Hasbrouck

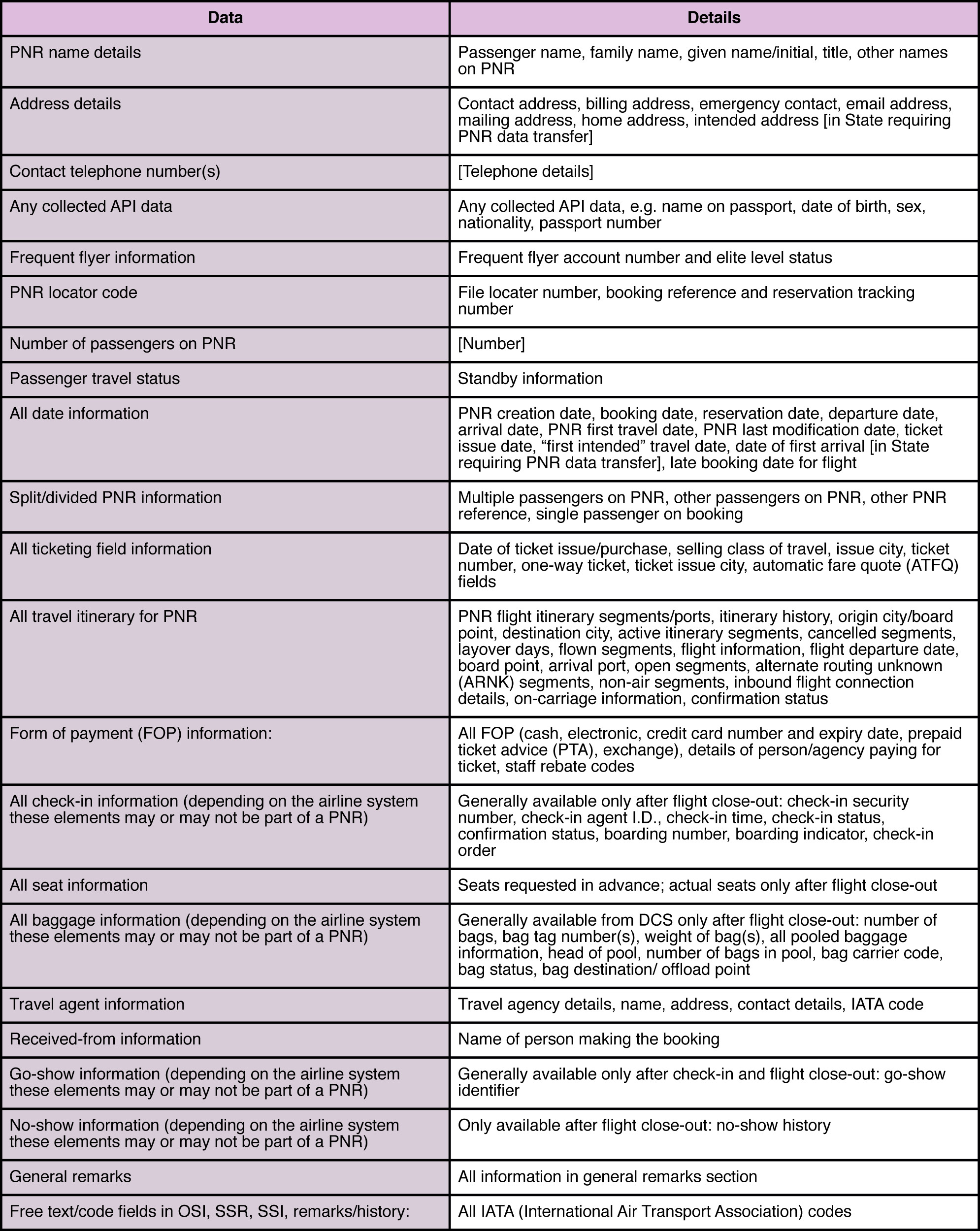

But what exactly makes this PNR data so attractive to governments? The following table, based on the 'Guidelines on Passenger Name Record Data' written in 2010 by the International Civil Aviation organisation, reveals just how much personal data is contained in this registry. Source: IATA

A PNR isn't necessarily created all at once. If we use the same agency or airline to book our flight and other services, like a hotel, the agency will use the same PNR. Therefore, information from many different sources will be gradually added to our PNR through different channels over time. That means the dataset is much larger than just the flight info: a PNR can contain data as important as our exact whereabouts at specific points in time.

What are the implications of all this for our privacy? The journalist and travel advocate Edward Hasbrouck has been researching and denouncing the PNR’s effects on privacy in the US for decades. In Europe, organisations like European Digital Rights (EDRi) have also criticised PNRs extensively through their advocacy and awareness campaigns. According to Hasbrouck:

PNR data reveals our associations, our activities, and our tastes and preferences. It shows where we went, when, with whom, for how long, and at whose expense. Through departmental and project billing codes, business travel PNR's reveal confidential internal corporate and other organisation structures and lines of authority and show which people were involved in work together, even if they travelled separately. PNRs typically contain credit card numbers, telephone numbers, email addresses, and IP addresses, allowing them to be easily merged with financial and communications metadata

Your individual PNR also contains a section for free-text "remarks" that can be entered by the airline, the travel agency, a tour operator, a third-party call centre or the staff of the ground-handling contractor. Such texts might include sensitive and private information, like special meal requests and particular medical needs. This may seem innocuous, but information like special meal requests can indicate our religious or political affiliations, especially when it is cross-referenced with other details included in our PNR. Regardless of whether the profile assigned to us is accurate, the repercussions and implications of that profiling are concerning – especially in the absence of public awareness about them.

As part of an investigation for her 2014 book Dragnet Nation, Julia Angwin, an award-winning investigative journalist from the US, requested the information about her that was being held by US Customs and Border Protection. She received 31 pages regarding her PNRs. When Hasbrouck reviewed that database, he discovered that the corporate travel agency Angwin worked with had routinely included notes in her PNRs describing the journalistic purpose of her trips; based on a form that reporters needed to send to their bosses for approval. In Dragnet Nation, Angwin explains that it is not at all far-fetched to imagine that her colleagues must have included more details in the “purpose of travel” field – information the travel agent would have entered in the PNR and subsequently into the government's hands. It is not uncommon for civil society organisations, think tanks, or media outlets to have a similar protocol with a travel agent. In countries with poor human rights records, this could expose these individuals to multiple risks.

At a border security conference in 2016, the facilitation and security manager for Swiss International Airlines, Marina Ripa-Braescu, was reported as saying: “For example, if they [the passenger] order a Muslim or kosher or vegetarian meal, you already start to know a little bit about that person.” After a social media backlash expressing concerns over possible “Muslim profiling” and many questioning the erroneous term “Muslim meal,” Swiss Air responded: "Airlines are not allowed and will never transmit data which may convey religion, health, political opinion to authorities."1 Although companies are not allowed to directly provide this information to the authorities, we still don't know whether airlines are proactively abiding by this regulation, or whether they have measures in place to ensure that non-security-related details embedded in our PNRs are protected and not shared. At the very least, Ripa-Braescu's comment exposed the problematic reality of collecting personal data from which other information about us can be inferred.

Disproportionate Data Retention

In the United States, PNRs are stored in the Automated Targeting System-Passenger (ATS-P), where they become part of an active database for up to five years (after the first six months, they are de-personalised and masked). After five years, the data is transferred to a dormant database for up to ten more years, where it remains available for counter-terrorism purposes for the full duration of its 15-year retention.

According to Edward Hasbrouck, PNRs cannot be deleted: once created, they are archived and retained in the Computer Reservation Data and You and/or Global Distribution Data and You (CRS/GDS), and can still be viewed, even if we never bought a ticket and cancelled our reservations:

“CRS's retain flown, archived, purged, and deleted PNR's indefinitely. It doesn't really matter whether governments store copies of entire PNR's or only portions of them, whether they filter out certain especially "sensitive" data from their copies of PNR's, or for how long they retain them. As long as a government agency has the record locator or the airline name, flight number, and date, they can retrieve the complete PNR from the CRS. That's especially true for the U.S. government, since even PNR's created by airlines, travel agencies, tour operators, or airline offices in other countries, for flights within and between other countries that don't touch the USA, are routinely stored in CRS's based in the USA. ((While this is routine, I've never heard of a travel agency or tour operator in Canada, the EU, or anywhere else that tells its customers that it has outsourced its customer database of PNR's to the USA, or asks potential customers for permission to create and store their PNR's and profiles in a system hosted in the USA.) Even Amadeus, the one major CRS based outside the USA, has offices in the USA with access to the full Amadeus PNR database.” from Hasbrouk

Under EU regulations, governments can retain PNR data for a maximum of five years, to allow law-enforcement officials to access it if necessary. The regulations state that after six months, the data is masked out or anonymised. But according to research by the EDRi, records are not necessarily anonymised or encrypted, and, in fact, the data can be easily re-personalised. In their document on the draft of the EU Data Protection Regulation, EDRi explained:

EDRi advocates a clear understanding of the term ‘identifiable’. Data are often presumed non-identifiable, or anonymous while it in fact still traces back to an individual. Personal data should not be regarded anonymous if the data can still be de-anonymized. ‘Masking out’ or depersonalisation of personal data are valuable security measures, but such measures should not be used to determine whether data are personal data or not. Recitals 23 and 24 should reflect this view point more clearly. Source: EDRI

No Security, No Control

PNR is a relatively old system, pre-dating the internet as we know it today. Airlines have built their own systems on top of this, allowing passengers to make adjustments to their reservations using a six-character booking confirmation number or PNR locator. But although the PNR system was originally designed to facilitate the sharing of information rather than the protection of it, in the current digital environment and with the cyber-threats facing our data online, this system needs to be updated to keep up with the existing risks. PNRs are information-rich files are not only of interest for governments; they are also valuable to third parties – whether corporations or adversaries. Potential uses of the data could include anything from marketing research to hacks aimed at obtaining our personal information for financial scams or even doxxing or inflicting harm on activists.

According to Hasbrouck, the controls over who can access PNR data are insufficient, and there are no limitations on how CRS/GDS users (whether governments or travel agents) can access it. Furthermore, there are no records of when a CRS/GDS user has retrieved a PNR, from where they retrieved the record, or for what purpose. This means that any travel agent or any government can retrieve our PNR and access all the data it contains, no questions asked and without leaving a trace.

To add a twist to the story, researchers Karsten Nohl and Nemanja Nikodijevic investigated the protection of passenger information in CRS/GDS. At the core of many of the weaknesses they discovered was the standard use of just two pieces of information to authenticate a booking: the six-character PNR and the user’s last name. _ The following video of Nohl and Nikodijevic's presentation at CCC Congress 2016 gives further insight on this_

Video: 2016 CCC Congress / Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? Becoming a secret travel agent. Karsten Nohl and Nemanja NikodijevicEven though our PNR contains so much personal and potentially sensitive data, instead of being treated as private, this number is actually printed on every piece of our luggage. It used to be printed on boarding passes, until it was replaced with a barcode that can be easily read using a number of apps and online platforms. The PNR is not treated with the same sensitivity as medical information, for example, even though as we've seen, it can carry very personal indicators.

Another concerning factor about a PNR is the weak formula that is used to generate it. The PNR is a simple six-character code, and in some cases, the formula is even more simplified: some providers, for example, iterate the first two characters sequentially, meaning all the PNRs generated in one day will have the same opening characters. Others reserve some codes for specific airlines, again narrowing the range of guesses an adversary has to make to access all the information registered there.

The PNR in the Wrong Hands

The travel agents, airlines and governments who continue to have access to our data are only part of the risk. Besides the threat of surveillance by governments and data corporations, many activists face surveillance risks from the targets of their work, which can include companies and public figures; individuals and entities ideologically opposed to their goals; and sometimes even other activists or people in their personal lives.

Because the PNR system is relatively antiquated, it makes it fairly easy to access records using very little information. Security researchers Nohl and Nikodijevic examined the system in 2016 and presented their research at the 33rd Chaos Communication Congress in Hamburg. There, they showed how they were able to go to Instagram, search for boardingpass" take a screen shot of the barcode from a ticket, and use that to access a PNR record through websites aimed at assisting travellers. This showed exactly how the personal data of a Human Rights Defender, a journalist, or even a lawyer invested in political struggle could be exposed to adversaries who might have interests in harming them or their work. The same researchers previously used PNR locators to determine that their users followed predictable patterns, and with that information they were able to brute-force their location records. Brute-forcing in this context means that they used easy-to-write automation scripts to test enough of the possible options to allow them to find individual records without knowing the exact code initially. Because of this research, and their responsible disclosure to the entities facilitating access to the PRN database, the brute force approach is no longer as easy, but the information in the database is still far from inaccessible to the general public.

Travel Data in Instagram Photos

Photos of our tickets or luggage tags pose particular risks because of the sensitive information printed on them. In addition to our name and flight information, they also include our PNR locator, though sometimes only inside the barcode. Even if we cannot "see" information in the barcodes or sequences of letters and numbers on our tickets, other people may be able to derive meaning from them. If we take and share photos on social media that include our tickets or tags, we need to make sure to edit the image before sharing it, to ensure we have removed not only clearly sensitive information like our name, but also any barcode or code sequence. If our travel is sensitive at all, we shouldn't share those photos. The same applies when sharing scans of our boarding passes or booked tickets with our organisations, political groups or even funders. The sharing of this information, unencrypted and unprotected, can expose PNR numbers and the data embedded in them – especially if there are adversaries interested in the personal data to use it against us or against our work. If we need to send a boarding pass or a booked ticket without editing it, in the case of grants and funding for example, using encrypted and safe communication is a good practice (while keeping in mind that the subject line is not encrypted).

Many of us share information about our travel plans both online and offline. In some situations, it may be important to inform only people we trust that we will be travelling and to keep the details of our travel sparse or vague. Even if we are only concerned about digital surveillance, it is important to consider what we share with people offline, since they can still make a digital record of it, like adding our travel dates to their online calendar. The only way to truly prevent our information from being entered into PNR and CRS/GDS is to abstain from using modes of travel that utilise them. But that may not be an option for those of us who attend conferences abroad, for example, or who have to travel for work or for our activism. In that case, taking certain measures is important to limit the diffusion of our personal data, at least within our points of control. Until the PNR system is reformed and more data-security measures are put in place, we need to be aware of exactly what kind of information these codes contain, and take common-sense measures to protect that information.

_ This article was written and researched by Paz Pena, Leil-Zahra Mortada and Rose Regina Lawrence._

Endnotes

1 "An Airline Exec Said In-Flight ‘Muslim’ Meals Could Be Used to Profile Travellers" 2016 Vice ↩

Shrinking Civil Space: A Digital Perspective

Data and Activism

Last-Minute GDPR Checklist for Civil Society Organisations

Data Baggage, Travel and Activism

What the Facebook?! To Leave or not to Leave

I Just Can't Quit You! Your Privacy Guide to Facebook

Activism on Social Media: A Curated Guide

Will You Be Attending? How Event Apps Collect Your Data

Applying for a Visa

What's in Your Police File?