When we travel, the visa application process is probably the stage when we have to relinquish the most data about ourselves, and yet it is also the point at which we have the least control over that data and how it is used. Whether or not an embassy decides to grant us a visa is fundamentally based on the information we are obliged by law to provide them – which can range from information about our intimate relationships to our personal health. Once we submit the long list of details we are required to provide, all we can do is await further instructions or the embassy's final decision.

Behind the scenes, embassies manage and analyse the large reserves of data from visa applicants, cross-referencing it from different sources, and categorising individuals into profiles upon which their visa is granted or denied. The profiles or categories can differ according to each country, and they are usually designated with codes for internal use only. Categories and profiles range from one embassy to the other, and this data is not usually made available. If a visa is not granted, embassies rarely provide a reason for the rejection. Even people who have been granted a visa before can be denied on further attempts, without explanation.

Visa applications are no longer just a matter of “official documents”: in today's digitised world, governments require new, technology-based data sources, which inevitably leads to more exposure for the applicants, and, in some cases, their social and personal networks as well. Some countries, like the United States or Russia, can require applicants to submit their social media profiles. Such invasive techniques are commonly justified under the pretext of “security,” “counter-terrorism,” or to counter “fraud.” Though governments are entitled and expected to protect their countries from these threats, mass collection of data to support visa applications has also become a threat to civil liberties and freedoms of expression and affiliation. Human Rights Defenders (HRDs), journalists, civil society workers, and politically-engaged artists are subjected to increased risk as a consequence of invasive data collection. It's essential for us to travel to support the causes we are working on – often to conflict zones or countries under increased government scrutiny. In some cases, we have to travel for our own safety if we have to leave our country of origin or residence. Yet visiting a certain country can also affect our ability to visit other countries in the future, especially because previous travels (as far back as five years or more) are included in most visa applications.

There are several concerns about the collection of data from visa applications that are particularly relevant for politically-engaged individuals. In addition to those mentioned above, political profiling is a primary concern. When the decision of whether or not we can travel is based on inferred or automated conclusions, it can give way to unfairness and discriminatory environments. This system of profiling, particularly in the case of visa applications, lacks transparency. In most countries and in most cases, an individual can't access the profiles created about them, let alone access it in the necessary time frame. This makes it nearly impossible for someone to rectify mistakes in the data, or, for example, have any knowledge or input on how something like a social media statement may have been interpreted.

Though some countries have data retention laws, most lack the necessary resources and infrastructure to enforce them or audit data collection departments. Others lack clear legal standings on data retention of foreign nationals. There are also concerns over the lack of independent reviewers to oversee if the data retention laws are respected. Even when such a review is possible, governments can always cite security concerns as grounds for keeping records on individuals or certain groups and communities. This can and has been challenged in the court of law when it was made public regarding communities (for example Muslims or people from predominantly Muslim countries), but it is not as easy when it concerns an individual, such as a Human Rights Defender or a journalist.

The countries in the Schengen Area of the EU have more advanced privacy and data retention laws compared to other geo-political areas, where data is kept “in the VIS [Visa Information System] for five years. This retention period begins on the expiry date of the issued visa, the date a negative decision is taken, or the date a decision to modify an issued visa is taken.”.1 And although “any person has the right to be informed about his/her data in the VIS" and "any person may request that inaccurate data about him/her is corrected and unlawfully recorded data is deleted,” it's rarely obvious how to access or remain informed about this information, or how to correct or delete inaccurate and unlawfully recorded data.

Another layer of complication arises when governments have bilateral or multilateral agreements on data sharing. These kinds of agreements are usually part of a wider security cooperation between or among countries. They form the basis of immigration policies and the enforcement of such policies to control immigration influx or detect possible border-crossing fraud. For individual visa applicants, it is no longer a matter of sharing their information with the corresponding embassy; now, an applicant's data can be shared with other governments without our knowledge. The US and the UK, for example, share immigration, visa and nationality information through bilateral agreements and platforms like the US Department of Homeland Security's Secure Real-Time Platform (SRTP) Implementing Agreement. 2 The SRTP allows foreign governments to submit biometric data on migrants for comparison against the US agency's own biometric data for border screening. A similar process happens between Canada and the US.

An example of multilateral cooperation agreements around data sharing is Five Eyes (FVEY), an intelligence alliance between the US, the UK, Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Though FVEY is not strictly about immigration and visa information, biometric data of arriving individuals and immigration data like personal details, fingerprints, flight history and credit card details, are all shared across borders within this alliance. Australia for example, runs a Border Intelligence Fusion Centre in Canberra, which often hosts permanent domestic and international representatives from other members of FVEY.

Though these agreements tend to be publicised under interests of national and border security, leaks (like the one by Edward Snowden) and statements by officials at FVEY have demonstrated that they are being used beyond their publicised capacity.

It is key to look at what kind of data is collected through the visa process, and how this data can or is used. In the following text, we will examine possible impacts and threats facing politically-engaged citizens.

Disclaimer: Our investigation into visa applications to the US took place outside the parameters of the Muslim Ban attempted by US president Donald Trump.

a) Visa Forms: Filling in our profile

In general, the visa application process differs depending on our country of origin. Some countries have agreements amongst each other that allow access to their respective citizens with only a passport or an ID. But for many, a visa is still a prerequisite to visit a particular country.

Visa applications can range in length, level of detail, and the amount of documentation we are asked to provide. Governments want to know who we are before giving us permission to enter their countries and we are legally obliged to provide this information accurately and completely. Even when the question is not applicable to us, we are still required to acknowledge reading it with a N/A (not applicable) answer. Failure to complete the application as required could yield rejection, further questions during an interview, or the application not being processed.

But what kind of data do they request, and what happens to this data once we've submitted it? Looking more closely at visa applications, we can see the extent to which we are expected to expose not only ourselves as the visitors to a country, but also to reveal information about our family members and even our current and past relationships. This type of exposure is more consequential when the concerned individual is a Human Rights Defender or a civil society worker of a certain affiliation that is of political interest to the country of destination. Not only will they be listed as part of a profiling system with all the provided data, but their contacts and family members risk being listed as contacts of a person of interest. The same thing could happen if the applicant has an extended family member who has been flagged as someone of interest due to their work or activism.

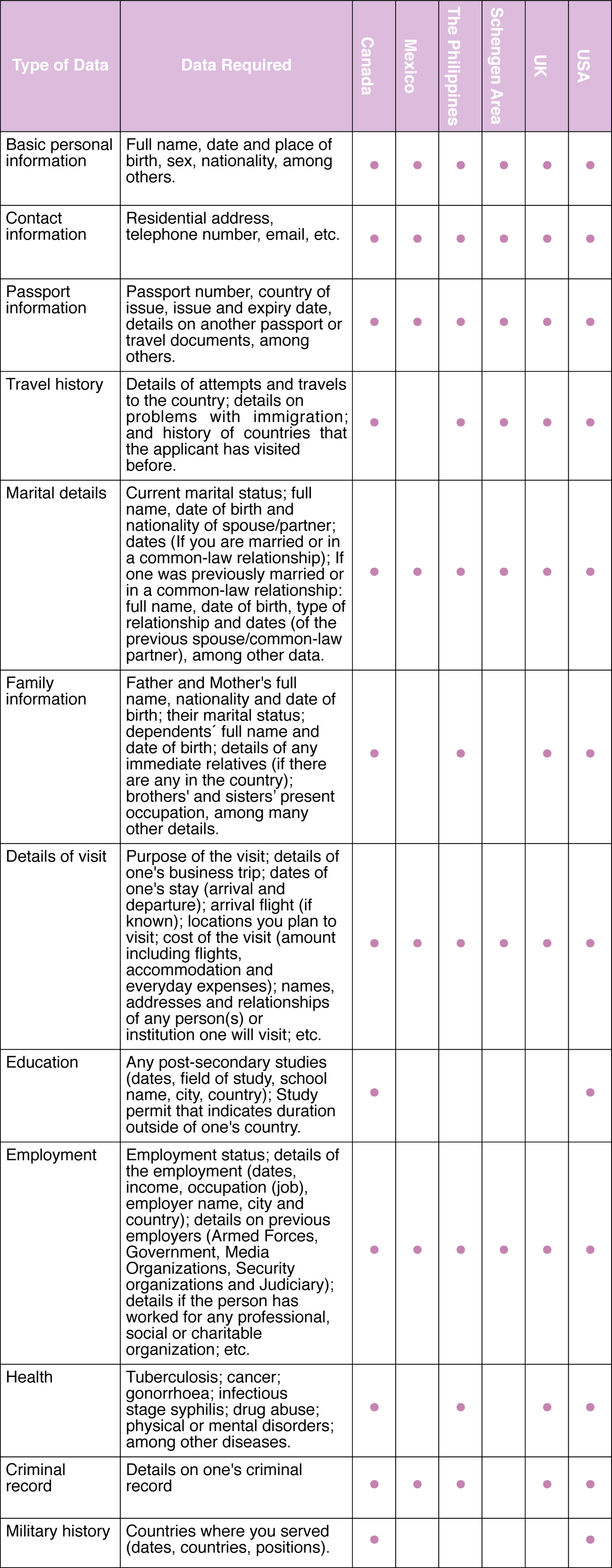

In this context, we have focused on popular destinations for international conferences, such as Mexico, the United States(US), the United Kingdom (UK), Canada, the Philippines and the Schengen Area countries. After examining visa applications and the associated documentation required by those countries, we were able to identify and categorise the types of data they require.

Let's take a closer look at the types of data that is required to obtain a short-stay visa. In most cases, a long-duration visa could require more exposure and more data.

In addition to the information above, governments will often ask for corresponding legal and official documents to back that information up. These documents usually contain additional data that is not necessarily included in the visa form, but nevertheless those details will be made available indirectly to the embassies. Some governments will even ask for our biometric data. Both the US and Russia have been known to ask for social media profiles, which in the US can require all social media handles for as far back as five years.

Only us and everyone else

When individual data is processed and analysed as collective data, it may reveal particular details about a certain community. That data, in turn, can allow for inferring other data, predictive analysis, and the examination of patterns and networks. The visa process is a chance for governments to do just that. Governments tend to harvest information about people, institutions and other entities that have a direct relationship with the visa applicant. In other words, every time they collect data on us, they are also collecting data about others around us.

Marital Details. The government of Canada, as an example, will potentially not only want to know the name, address or duration of our relationship with our spouse or partner (among other details), but they could also ask for the same amount of data about our previous relationships.

Family information. In visa applications for Canada, the government can request thorough data about our parents, siblings and dependents, such as their full names, their relationship with us, their date and country of birth, marital status, present address and occupation. Ah! And if they are dead, we have to provide the date and city of their death.

Details on your visit. Most countries ask for details of the visa applicant's visit, which may include documentation of the applicant’s financial situation. But some countries want to know more about who is economically involved in supporting our visit. For example, the US, UK and Schengen Area countries will request details about the person(s) or entity(ies) paying for the trip. In Canada, for instance, the applicant may be asked to provide a letter of invitation from the person inviting her or him, which must include specific information about both the invitee and the host.

Sensitive Data is a Fundamental Part of Our Profiling

Sensitive Data is considered 'sensitive' because of its consequences for our privacy, fundamental rights and civil liberties; for that reason, greater protection for such data was always required, and at times, certain types of it was not allowed to be collected. Traditionally, this category of data contained information that could reveal an individual's political ideology, union affiliation, religious and spiritual beliefs, racial origin, health records or sexual information, and data related to criminal or administrative offences. In the context of the 'war on terrorism', this is no longer the case. New laws have been passed that allow embassies to collect sensitive data under the auspices of national security. Bilateral and multilateral agreements on surveillance have given governments much more power and access to collect this data and share it among them.

Health. The US asks for the most details related to a person's health. If an HRD wants a visa to attend a conference in the US, the embassy could require them to fill out a form with an extensive list of illnesses or behaviours as specific as Gonorrhoea or drug abuse. The US, Canada and the Philippines could also ask individuals for information on their physical or mental disorders.

Other sensitive data. Sensitive data related to ideology, union affiliation, and religious and spiritual beliefs could also be inferred from data required by governments. For example, the UK can request a letter from the applicant's employer outlining the reason for his or her visit, whom the applicant will be meeting with and details of any payments or expenses involved. Meanwhile, Mexico can ask for a letter from the public or private organization or institution that is inviting the foreign person to participate in any unpaid work in the country, including the purpose of the visit and an estimated time of stay.

Sensitive Data can be critical for everyone, but especially for HRDs: first, because that kind of information can be used by third parties to interfere with their work and safety. The access to this information can facilitate a variety of threats: slander campaigns, cyber harassment, and even physical threats in certain countries.

All of the factors listed above could expose a wider network of individuals and entities in the visa applicant's network to profiling, even if they are no longer interacting. If people in that network apply for visas in the future, their data will be cross-referenced with ours and we will be forever linked to each other, for better or for worse.

The Plot Thickens

Let's thicken the plot by throwing in a twist: the introduction of third-party contractors.

In certain countries, embassies contract a third-party company to handle visa appointments and/or communication with the applicant, mostly in the first phase of the application.This could be for a variety of reasons, but it is commonly tied to security concerns over embassy personnel in that country.

Many of these companies work with embassies of various countries based in their country of operation, and thus have access to a wider range of data over the citizens. A contractor like Gerry's Pakistan, for example, connects a lot of the dots we would like to highlight.

According to Gerry's website, they not only handle visa applications for “18 countries including the UK and the entire Schengen area”, they also work on:

- Handling 11 International Airline companies in Pakistan from marketing to ticket sales and human resources

- Officially representing and handling FedEx in Pakistan since 1989

- Operating an Internet Service Provider and a Big Data centre in Pakistan

Following the good practice of looking at the Data Use Policy, we checked Gerry's privacy policy on the visa application website.

As seen in the image above, the text, which is still posted at the time of publication, doesn't say much about Gerry's use of data – a point of concern, considering the amount of data that Gerry's has access to and their ability to cross-reference it via the other services they provide. In the case of travel, Gerry's can cover the whole process of an individual's trip to a conference – from using the internet to communicate with the organisers, to the visa application, to any post he or she receives, and even the flight booking itself.

The absence of a data policy doesn't necessarily mean that Gerry's handles the data irresponsibly or for ends other than what is stated in their mission. More often than not, companies' Data Policies are vague and loaded with open-ended language. Let's take an example of Facebook's Data Policy by looking at a summarised version from Tactical Tech's Lost in Small Print.

As we can see, though this policy is much more detailed than Gerry's, as users we still can't fully understand what happens to our data. Who are those “third party companies,” for example, that Facebook shares our data with? And to what extent are they sharing it?

The issue is no longer just the invasive and extensive nature of the information that embassies worldwide are collecting and sharing across different governments; it is also about the third-party contractors who are dealing with this data. As citizens, we have very little control over how our data is shared and stored; let alone the almost non-existent channels for accountability and review. But if we are at least aware of the risks and better understand what is happening with our data when we apply for a visa, we can make more informed choices. Our safety and the work we do is increasingly linked to the our personal data, especially as people who are engaged politically through activism in journalism, art or as members of civil society. It is also important to stay informed about the processes behind-the-scenes and, for those who choose to, join the ongoing work on data privacy that multiple organisations are leading.

_ This article was written and researched by Paz Pena and Leil-Zahra Mortada _

Endnotes

1https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/borders-and-visas/visa-information-system_en

Shrinking Civil Space: A Digital Perspective

Data and Activism

Last-Minute GDPR Checklist for Civil Society Organisations

Data Baggage, Travel and Activism

What the Facebook?! To Leave or not to Leave

I Just Can't Quit You! Your Privacy Guide to Facebook

Activism on Social Media: A Curated Guide

Will You Be Attending? How Event Apps Collect Your Data

Booking Flights: Our Data Flies with Us

What's in Your Police File?