Civil society organisations and grass-roots activist groups are increasingly using online platforms and apps for event planning and organising. Some of them use free services offered by third parties, while others outsource app development or develop their own apps mostly with the support of third-party companies. These websites and apps, however, will inevitably collect data about the organisers and the attendees, which is then aggregated and deployed in marketing and even political profiling. The data from organisers’ accounts can then be used by the platform and third parties – and sometimes the authorities – to compile a history of the organisations’ activities.

This poses an important question about the responsibility of event organisers to be transparent in informing their participants about their data-use policies in clear and accessible terms. What data is collected, by whom and who has access to it? How is it being used, stored and analysed? How long is it kept and what are our options for opting out?

Planning, hosting or attending an event, whether a conference or a fundraising concert, can present potential risks in our data-driven society, particularly for human rights defenders, journalists and activists. In certain countries, merely attending an event, be it a workshop or a conference, can put a human rights defender at risk. In Egypt, for example, the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies canceled its annual training program on human rights, which it had held for the past twenty-two years. Explaining the decision in a published statement, the institute wrote, 'It has become impossible to find a safe space for youth for learning and creativity. Prisons have become the fate of all those who care about public matters.' Smear campaigns against NGOs in pro-government media outlets have made public outreach more difficult and dangerous: activists report threats of violence from ordinary Egyptian citizens during public activities." This is just one example of the way, for multiple reasons, states and corporations alike are interested in obtaining your information. From security to marketing, we are reduced to data that is used beyond your control and your knowledge. This makes attending an event yet another threat vector, especially when your data is not secured by those who plan the event or the platforms it is outsourced to.

In September 2011, two iPads were stolen from an Eventbrite employee which contained data collected at one of their customer’s events. Eventbrite describes itself as the “world’s largest event technology platform,” building “technology to allow anyone to create, share, find and attend new things to do that fuel their passions and enrich their lives.” Kevin Hartz, Eventbrite’s co-founder and CEO at the time, wrote in a blog post on the company’s website that the “potentially compromised data included full credit card information for 28 people who bought tickets for the event; names and email addresses for some customers who bought tickets online for the event; and the names, email addresses and last four digits of credit cards for some fans who bought tickets at the event. The full credit card information was erroneously stored due to a glitch in the iPad app that has since been fixed.” Though the company notified the attendees whose email addresses were potentially exposed, and immediately alerted authorities and initiated a remote password-lock and a wipe of the data on both devices, Hartz went on to say that he knows that having one’s personal data compromised is a violation of the trust put in Eventbrite, and expressed his apologies to the people affected.

Though this case resulted in relatively minimal harm to the people whose data was compromised, it does highlight an alarming vulnerability when it comes to the collection of personal data in the context of political events and conferences.

Controversy arose more recently, in 2017, when those who had registered for a talk by far-right commentator and writer Milo Yiannopoulos at the University of Colorado at Boulder received an email prior to the event reading: “We know who you are, tonight we will know your faces. The identities of attendees will be released to the public on a list of known Neo-Nazi sympathisers. We do not tolerate fascists.” Eventbrite again came under the spotlight for an alleged hack behind the leak of the email addresses; though a further police investigation found that the responsible party was rather the organisers, who had sent info to the attendees using the “To” field instead of “Bcc.”

In this article, we take Eventbrite as a case study not as an attempt to single it out, but rather as a high-profile example of what is becoming common practice across the most-used event organising platforms.

When you register at a conference, who gets your data?

"Recently, I was browsing the website of a conference at which I’m presenting and saw a link to a list of registrants. One click later, I possessed a nice Excel spreadsheet containing the names, companies, and “badge type” for the seven hundred attendees. Hmmm. At the bottom of the spreadsheet, I noticed a second tab: “Sheet1”. Clicking on that showed a smaller list of a hotel chains' participants that included emails. Yikes! This got me thinking about who gets our conference information when we register."

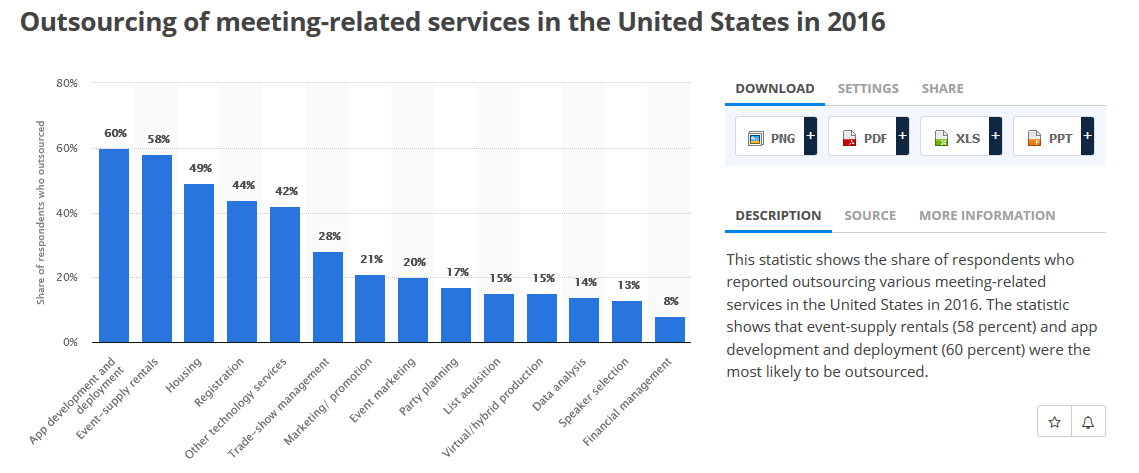

So wrote Adrian Segar, the author of Conferences That Work (2009), in 2013 about the discussion in the industry around attendees’ personal data: how it is collected, managed and stored. That conversation is only becoming more relevant. According to Statista, conference and event organisers in the US are increasingly outsourcing everything from app development to technology services like registration and data analysis to specialised companies.

With the use of these services, conference organisers can easily access and analyse your information to make data-driven decisions that have a direct impact on the success of their events, whether they’re looking to enhance attendee experiences, improve registration rates or provide measurable ROI (return on investment) to other parts of the business, like sales or marketing.

Nevertheless, we need to assess the impact of these data-driven services, especially when activists, human rights defenders and journalists are among those attending. The data traces of their attendance – as well as their activities at the event itself – may be used by local and national authorities to crack down on them. For example, in 2007 Algerian police broke up a conference aimed at reconciling a longtime political conflict. In 2015, Lithuanian authorities imposed a five-year ban on Latvian human rights activist Aleksandrs Kuzmins, just as he arrived in the country to take part in an international conference. In 2016 a Chinese activist was charged with “subversion” due to his attendance at the 2014 Interethnic/Interfaith Leadership Conference in Taiwan, organised by the US-based non-profit group Initiatives for China. In December 2017, the Argentinian government blocked entry to 60 activists ahead of hosting a World Trade Organization conference (which is not uncommon for these kind of events).

Conference organisers and attendees should be aware of the data traces that are produced before and during these events and take measures to minimise the effects. To understand how, let's look at the ways different conference platforms work and the extent to which personal data is their main asset.

How Conference Apps Track Your Data

It is not cheap to develop and run your own app for an event. It is rather expensive, time consuming and piles work on top of the strenuous workload involved in organising events. Funds are also not always accessible for organisations to develop their own app especially when it is needed like in the case of large-scale events. CSOs need to find a developer, provide a briefing, have an understanding of tech, needs and requirements for their event, and see it through.

With the lack of viable alternatives – secure, open source, & user-friendly options; organisations are left with a yes or no question: to use corporate platforms or not to have an app for the event. Deciding to use an off-the-shelf app for your event is a matter of trade-offs and compromises when it comes to user privacy and the collection of data. Most of these services offered at an affordable price or for free, are built on monetising user data - be it an organiser or a participant. Collecting data for marketing, ad targeting, profiling and often the sale of data to other parties.

Should you as an organiser opt for using a third-party app for your event, there are certain things that can help better control the use of your data and that of your participants.

Looking into the third-party app you are planning to use: what data they collect, who they share this data with, how long they store it and how it is stored. It is important to also look at the location of their servers as this will determine what data protection jurisdiction they fall under and who has access to it. Being transparent with your network about what platforms you are using and the data use policy on those platforms; and most importantly, giving the participants the option to opt out from sharing their data, and providing them with an alternative to the app is a good practice to deal with some of the trade-offs made when choosing to use a conference organising app.

Here we take a closer look at a selection of commonly used apps for conference organising and we examine the data they collect to show a set of vulnerabilities and responses from organisers to inform their participants. We do this not to cast judgement on the organisers but to pinpoint important issues around privacy and data that are key to civil society organisations and HRDs. If this highlights anything beyond the vulnerabilities, it is the need for secure privacy-oriented open-source apps for organising events.

Conference organising apps that collect your data!

Sched.com is one of the commonly used apps for conference-scheduling and conference-planning that comes with multiple services, like a customised website for the event, social network features, a print-ready programme, session reports and survey integration. Sched.com's app is used by various organisations and key annual events with sensitive personal information outside of the CSO sector. Sched.com hosted the app for ICANN Hyderabad57, RightsCon organised by Access Now, and even medical conferences which tend to include sensitive data on attendees such as the US-based annual OCD Conference attended by medical practitioners and people with OCD and their families. This app tends to have access to:

Location

- Approximate location (network-based)

- Precise location (GPS and network-based)

Photos/Media/Files

- Read the contents of your USB storage

- Modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Storage

- Read the contents of your USB storage

- Modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Other

- View network connections

- Full network access

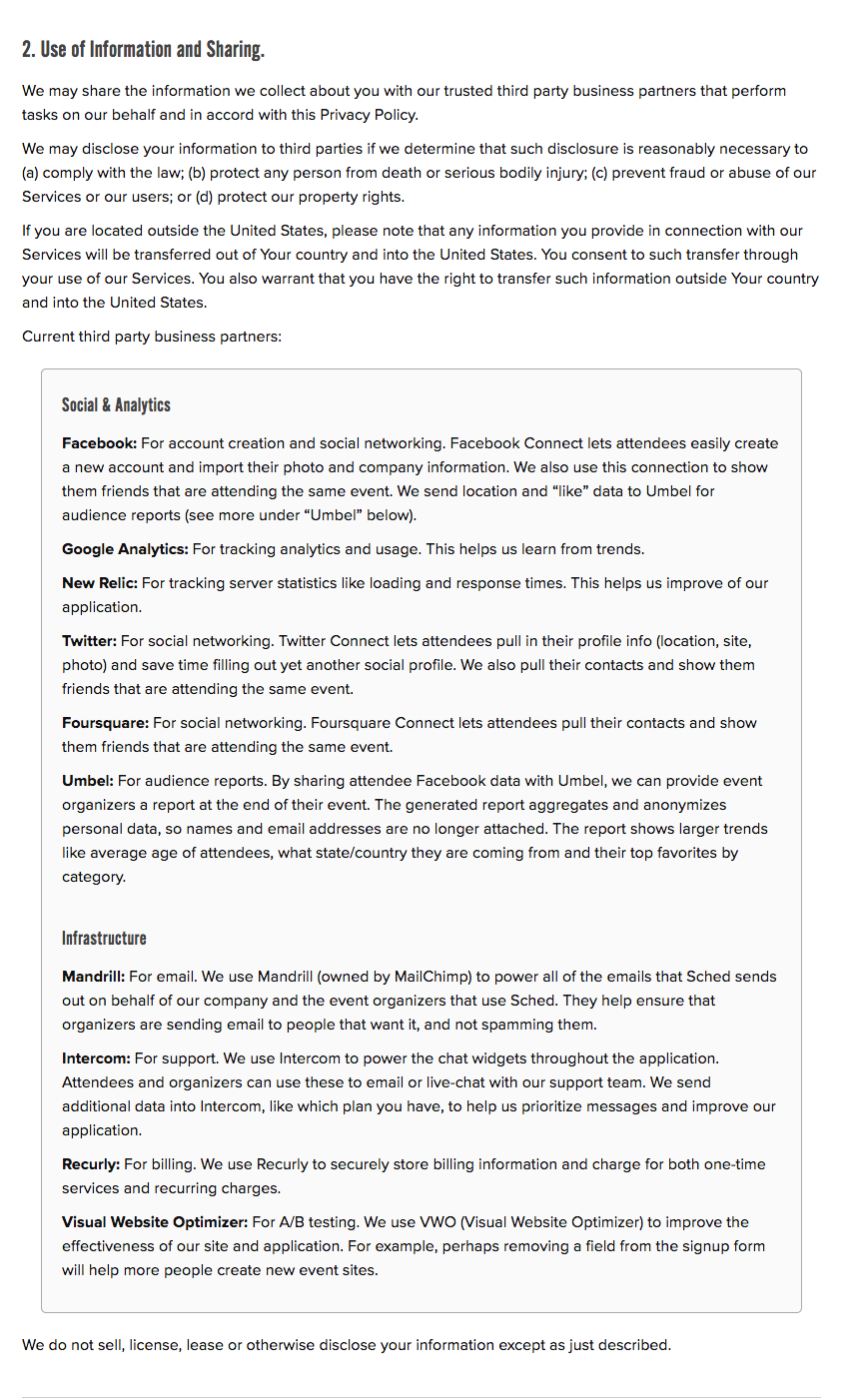

It is worth taking a look at the data-use policy of Sched.com, which we have documented with a screen-capture below on April 16, 2018.

RightsCon explicitly explains what data is collected when the participants attend their event and use the designated platforms like Eventbrite and Google in addition to Sched.com: "When you submit information on our site using third party forms, like the registration form powered by Eventbrite, the schedule by Sched, or the Google Forms to propose program sessions, data may be collected by those vendors and processed subject to their terms of service."

Participants are also advised to reconsider registering if they deem the share of their data risky:“If you believe that you may be at risk by putting your name or other personally identifying information to a form on the Site, we would encourage you to consider the implications before doing so.”

CrowdCompass is another popular app that have been used by various organisations like the NAACP National Convention (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), the Women and Girls Foundation, the World Health Organisation – South-East Asia, the International Civil Society Week 2017 (ICSW) among others. The app is also used by events like the Global Terrorism Risk Insurance Conference organised by the Australian Reinsurance Pool Corporation (ARPC) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD); and also in CyCon – the International Conference on Cyber Conflict organised by the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence.

Despite the sensitive nature of the events that use CrowdCompass, the app tends to have access to:

Identity

- Find accounts on the device

Calendar

- read calendar events plus confidential information

- add or modify calendar events and send email to guests without owners' knowledge

Contacts

- find accounts on the device

- read your contacts

- modify your contacts

Photos/Media/Files

- read the contents of your USB storage

- modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Storage

- read the contents of your USB storage

- modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Wi-Fi connection information

- view Wi-Fi connections

Other

- receive data from Internet

- view network connections

- pair with Bluetooth devices

- access Bluetooth settings

- full network access

- run at startup

- use accounts on the device

- control vibration

- prevent device from sleeping

- read Google service configuration

Zerista, which “gives your events an intuitive, interactive digital space to guide your customers through all the most important content, personalized for their needs,” has been used in various conferences and events. The platform comes handy when the event has a massive attendance list which can render other forms of communication rather tedious and impractical. This leaves little option for organisations putting together large-scale events who opted for using this app, like the AWID Forum which brought together over 2000 women’s rights activists and allies; and other events of the same magnitude. Those events used the conference app Zerista developed by JackRabbit Systems, Inc. The app - according to its page - “delivers best in class SaaS technology, engaging users and producing data-driven results you can use to better your business in leisure, travel and event markets.” A look at various Zerista app profile pages for various organisations on Google Play shows that it tends to have access to:

Identity

- Find accounts on the device

- Add or remove accounts

Calendar

- Read calendar events plus confidential information

- Add or modify calendar events and send email to guests without owners' knowledge

Contacts

- Find accounts on the device

Location

- Approximate location (network-based)

- Precise location (GPS and network-based)

Photos/Media/Files

- Read the contents of your USB storage

- Modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Storage

- Read the contents of your USB storage

- Modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Camera

- Take pictures and videos

Wi-Fi connection information

- View Wi-Fi connections

Other

- Read sync statistics

- Receive data from Internet

- View network connections

- Create accounts and set passwords

- Pair with Bluetooth devices

- Access Bluetooth settings

- Full network access

- Read sync settings

- Run at startup

- Use accounts on the device

- Prevent device from sleeping

- Toggle sync on and off

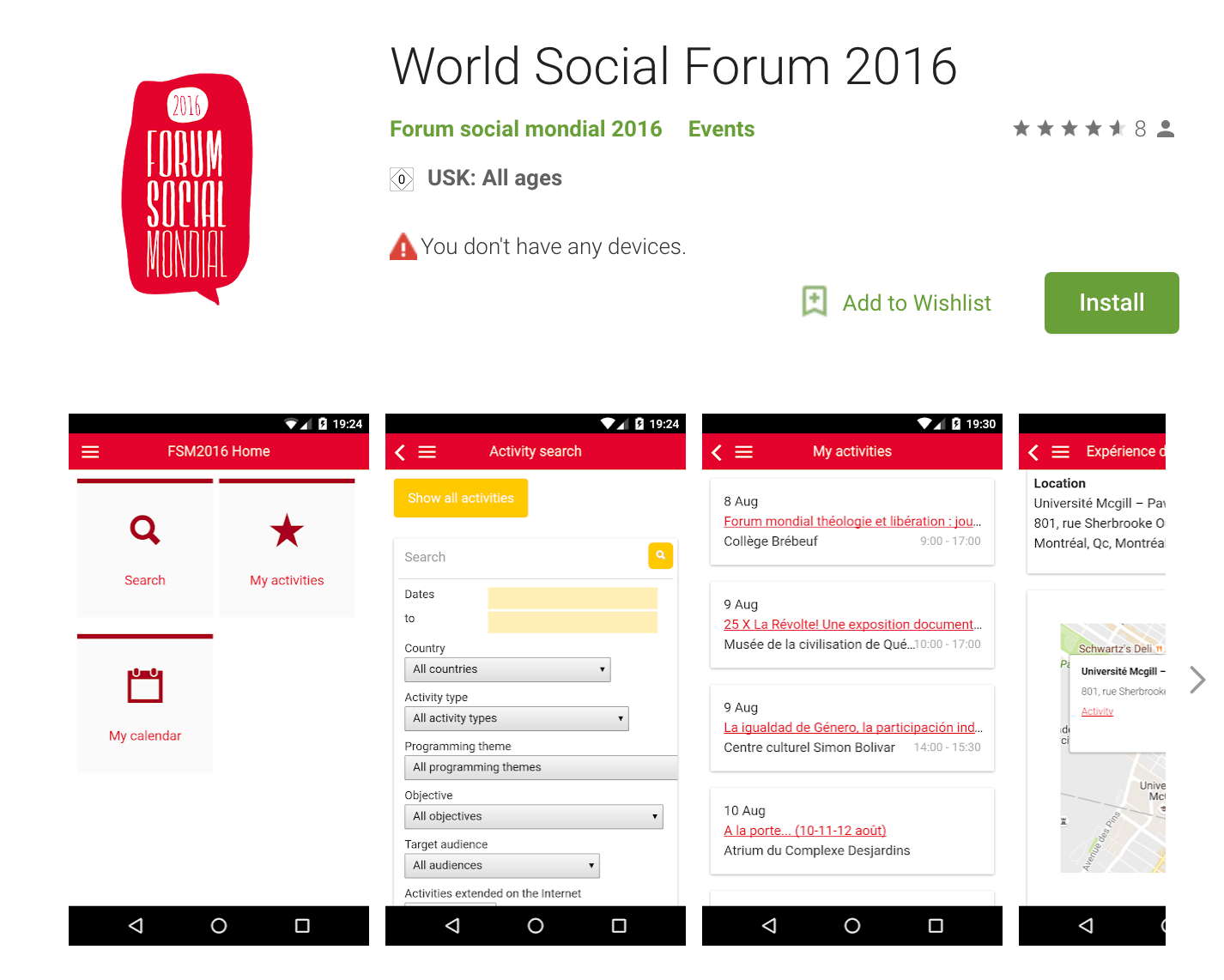

The World Social Forum, an annual meeting of civil society organisations and activist networks, developed its own conference app for the 2016 meeting in Canada, which had access to network connections and full network access which means that they the ability to track location even if they haven't requested location permissions. It worth noting that it will continue reporting back information as the long as the app is installed. A rather limited amount of information highlights not only better privacy for the participants but also the disparity in data collection – as opposed to initiatives that opt for outsourcing this task due to lack of resources. The smaller local World Social Form (2016) in Porto Alegre had an app developed by the third-party company Touch Interativa, which according to its Google Play profile, had access to:

Phone

- Directly call phone numbers

Photos/Media/Files

- Read the contents of your USB storage

- Modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Storage

- Read the contents of your USB storage

- Modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Wi-Fi connection information

- View Wi-Fi connections

Other

- Receive data from Internet

- View network connections

- Full network access

- Control vibration

In addition to what we've seen with the apps mentioned above, everything conference organisers want to know about users could potentially be asked for and stored by these platforms. The most common data fields, according to the Terms of Services from a number of different platforms, are:

- Personal identification: name, sex, city, country, dietary restrictions, profile description, personal photos, etc.

- Contact information: email, mobile phone, address, etc.

- Professional information: organisation, employer, etc.

- Social media: personal profiles on LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, among others.

- Activities: data about your activity on the app through functions that create meetings, send messages, build your schedule, etc.

- Friends: the list of attendees in your social networks.

- Billing information: If we choose to make an online purchase through the app, the company can require and collect information such as credit card numbers and related account and billing information, invoice-related information and other data required to process the order.

- Log files: the information inside the log files when an attendee uses the app. This could include internet protocol (IP) addresses, type of browser, Internet Service Provider (ISP), date/time stamp, referring/exit pages, clicked pages and any other information the browser can send.

- Mobile device data: such information may include your mobile device type, mobile device ID, and date and time stamps of software use.

The Market: Your Data Is the Product

With marketing as their principal objective, these platforms are designed to amass data in order to create detailed profiles of attendees, which can then be used for commercial reasons. Alon Alroy, Bizzabo's co-founder, has compared these types of platform features to what happens with Amazon when “you are looking at a pair of shoes and then you see shoe ads chasing you all over the Internet.”

The market for conferences and public events is increasingly dominated by companies offering technology platforms to gather, manage and analyse data. Evenbrite and Bizzabo are the two most popular, but there are many more. According to the Event Manager Blog, conference apps have been around since 2008, with over 4,100 of them created each year.

These platforms have designed tools especially for companies to increase their publicity and improve their sales. Some apps are completely free for organisers and attendees; others charge the organiser per attendee; and others according to the number of events they will manage. Each model has one asset in common: data (from the organiser, but most importantly from the attendees).

Of course, the company who owns the app and the organisation behind the event or conference will have access to some of that data. In addition, your data could be accessed by third parties who have agreements with the company who owns the app. These agreements are often mentioned in data use policies, though they rarely define who these “third parties” are, what function they have or what they can do with your data. Also, for legal reasons, companies must hand over some of that data to government agencies when it is lawfully required. But other third-party companies will have access to some of this data, too. Companies tend to give three main reasons for the collection of data: to operate their platform, to enhance their service, and to deliver better targeted advertising.

Your Data Lost between Server Locations and Country Regulations

“If you are located outside the United States, please note that any information you provide in connection with your Services will be transferred out of Your country and into the United States. You consent to such transfer through your use of our Services. You also warrant that you have the right to transfer such information outside Your country and into the United States.” [privacy policy – www.sched.com]

Different countries have different data protection laws. The location of the app’s parent company and where their servers are located determines the jurisdiction it operates within. It is always important for both the organiser and the users of an app to find out where their servers are based, as this is where your data will actually be located and can impact how your data is governed. Similarly, it is important to determine if the servers are located in a country with a compromised record when it comes to data protection and privacy laws and regulations.

The Eventbrite Case

The Eventbrite platform allows its customers to create an event page, publish it across Facebook, Twitter and other social-networking tools directly from the site's interface, register attendees, track attendance and even sell tickets. The company is a classic Silicon Valley startup, financed by venture capital from its official launch in January 2006.

Eventbrite is commonly used for events related to journalism, activism and human rights, including The Global Investigative Journalism Conference (the world’s largest international gathering of investigative reporters), The Amnesty International 2017 Annual General Meeting and Human Rights Conference, and the Conference on the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

This should raise alarm, especially when we take a closer look on who attends these conferences, and the sensitive work they do. Also considering that, on multiple occasions, Eventbrite’s co-founders have stated how important data is for their business model. Kevin Hartz has said: “We are really data fiends. I think we were the first to publish the metric of yield-per-share [every time an event attendee shares news of an Eventbrite ticket purchase on Facebook, it drives an additional $2.53 in purchases, the company has found]. Our head of financial analysis comes from a physics background. It’s that notion of testing, experimenting, observing, and data collection that has helped us to discover these trends and then to optimize them.”

Recently, Julia Hartz, Eventbrite’s co-founder and current CEO, pinpointed the collection of data as a crucial method to achieve complete personalisation in Eventbrite’s offer to users: “We want to be able to whittle that down to three to five hyper relevant events for each consumer. We think consumers should expect that in this day and age of technology with big data and algorithmic recommendations, and we have a fairly sizeable data team that’s working on this problem right now.”

As stated in the company’s Privacy Policy, Eventbrite – and companies like it – collect and keep personal information provided by the conference organiser, attendees and anyone visiting their website. In addition to all the personal data that users voluntarily submit to the company, Eventbrite builds profiles of its users, as they “may associate other Non-Personal Data (including Non-Personal Data we collect from third parties) with our Personal Data.”

Third parties on Eventbrite?

As it can be seen in Cookiepedia.co.uk, Eventbrite’s website has 51 third-party cookies, which means that there are 51 cookies (small amounts of text) stored in the user’s computer that have been created by a website from a domain other than Eventbrite.com, with the goal of tracking, collecting, analysing, processing, aggregating and selling that users’ data. Also, as was revealed in documents leaked by Edward Snowden, individual and group profiles can also potentially serve as assets to law-enforcement agencies for national security purposes.

According to Cookiepedia.co.uk, the cookies found on Eventbrite’s website lead to various trackers and companies. To name a few: Facebook, Google, Twitter, Atlas Solutions (owned by Facebook), Advertising.com (AOL), and the gigantic data management platform Oracle BlueKai that possesses thousands of personal attributes and socio-psychological profiles about hundreds of millions of users (not acquired from Eventbrite solely of course).

Eventbrite uses social media as a fundamental resource for profiling its customers. As is stated in their Privacy Policy: “For example, if you connect with Facebook, we store your Facebook ID, first name, last name, email, location, friends list and profile picture and use them to connect with our Facebook account to provide certain functionality on the Services, like recommending events that our Facebook friends are interested in and sharing the events you are interested in, or attending, with certain groups of people like our Facebook friends.”5

Highlighted by this example, if you attend an event hosted by Eventbrite, they have access to more of your personal information including political views. And they also could have access to “shadow contact information” (i.e. contact lists that people share with social media) which give companies enough information to map your social connections.

Political Profiling with Eventbrite Data

This model, based on building delegates’ profiles with their data, has been increasingly used for electoral goals, at least in the United States. As Chad Barth, a senior political and government relations manager for Eventbrite, has stated: “The tactics that campaigns deploy to connect with voters evolve as new platforms are introduced each election cycle. Candidates today are leveraging town halls and rallies to not only shake hands and take selfies, but to capture actionable data about some of the most valuable supporters.”6

By collecting potential attendees’ information ahead of time, political campaigners can see who actually showed up at a campaign event, versus who only signed up online but did not attend: very useful data in determining someone’s overall level of commitment. Likewise, data collected from Eventbrite can be synced with a user’s Facebook page, which contains a wealth of personal information that is incredibly useful to political campaigns.7

Donald Trump’s presidential campaign team reportedly used Eventbrite. Supporters filled in online registration forms for events, which asked for personal information including names, emails, mailing addresses and cell phone numbers. A key section was called “Other information,” where campaigners could “collect specific information that allows the campaigns to slice and dice the attendees into groups and follow up accordingly. All of the information collected on Eventbrite can be exported and, thus, analysed by a data scientist.”8

According to reporting by The Daily Dot, “every presidential campaign—not to mention thousands of down-ballot races around the country—have stopped taking the data-gathering potential of live events for granted. Virtually every GOP presidential candidate uses (or used, as the case may be) Eventbrite, and their opponents across the aisle employ similar systems developed by left-leaning firms available only to Democrats.”

The Risks of Online Registration Forms

Not all conferences need to be managed by high-tech platforms; most organisers opt just for web registration. With a very simple (often free) digital technology, a conference organiser can automate registration and manage attendees’ data in a simple spreadsheet. What doesn’t change is the demand for data. Sometimes, the excuse will be ensuring security at the conference. On other occasions, mandatory data will be demanded just for the basic identification of attendees and some statistical analyses post-conference.

The amount of mandatory data required depends on the nature of the conference: usually, if no official or high-risk persons are attending (as with events organised by civil society or academia), a name and an email address is sufficient to register someone. However, many conferences demand more personal data such as gender, country and organisation, so they can create an overall profile of who attended. Increasingly, many conferences ask for social media handles.

If it is an official conference coordinated by a government and/or intergovernmental organisation, even more personal data will be required. The range of identification information could include name, gender, date of birth and passport data, email, phone number, personal and work address, etc.

Furthermore, under the pretext of security, our official identification (including personal photo) can be checked on-site. As is pointed out in the section "Security and Access to the Premises" of the Internet Governance Forum’s Guidelines for Participation:9

Participants are required to present their confirmation letter to the Forum’s Registration Desk, together with a picture ID issued by a national authority of a state recognised by the United Nations, in order to obtain an IGF badge.

Data for Security Clearances

Collecting some data is a must for performing security clearances, which means the safeguarding of information starts during registration. Typically, a security clearance is a thorough analysis of attendees’ personal data previously required in paper and/or online forms. Then, a security/personnel officer must certify that he/she has verified the accuracy of the information stated by the attendee. This is the reason why, in general, these types of conferences will take several days before confirming our attendance at the event. Some conference organisers even ask for other details, like the attendees’ supervisors’ data, to double-check the identification verification.

Governments and intergovernmental organisations usually use procedural guidelines tailored for classified conferences. For example, in the US, the Department of Defense has standardised the security measures of conferences and other gatherings during which classified information is disseminated. In this way, they have established that access to classified conferences or specific sessions should be limited to persons who possess an appropriate security clearance and a “need-to-know.”10

Using Social Media Data to Profile Activists

In December 2017, the Argentinian government hosted a World Trade Organisation (WTO) ministerial meeting, and at the last minute, decided to revoke accreditation for around 60 people and deported two delegates who attempted to the enter the country. Their excuse? “Security reasons.”

According to Argentina’s foreign ministry, they had blacklisted NGO officials “who had made explicit calls for manifestations of violence through social media, expressing the intent to generate schemes of intimidation and chaos.” The activists denied the accusation, pointing out how measures like this could affect freedom of expression.

The incident reveals two important aspects of security clearances at conferences: first, how crucial data collected by conferences is to building an attendees’ profile, but also how that database is cross-referenced with other sources of information (like social media); and second, how such interpretations of attendees’ data could be misleading.

The Politics of Attendees’ Data

Conference organisers are generally not transparent about how attendees’ personal data is going to be used and stored, or for how long. Collecting names and organisation details from attendees usually falls within the ambit of legal data protection frameworks, and it is important to inform attendees how their data might be used, obtain their consent and work to handle and store that information securely.

The lack of clarity about what happens to attendees’ data can be problematic, especially for activists, human rights defenders and journalists who need to protect their personal information from third parties. In conferences coordinated by governments or intergovernmental organisations, it is valid to ask whether attendees’ personal data will be shared with another entity (e.g. the police) and for how long. For instance, if activists that have been harassed by the local police are attending an official intergovernmental conference, having access to a complete list of activists’ personal data could be very useful for police but very dangerous for activists.

Who Is Behind the Online Registration Platform?

It can be difficult to determine who is behind an online registration platform. If there is no visible information, it could be inferred that the conference itself is managing the platform and the data – but that could be anything from a self-made platform to Google Forms services.

In the few instances when there is transparent information about a third party managing online data registration, usually that means a company specialising in technology platforms, such as Bizzabo or Eventbrite, is behind it.

This lack of clarity makes it even more important to determine who is handling our personal data and how securely. Some event-management technology companies, for example, have a legal right to use our data for their own marketing purposes. If so, they likely store that registration data somewhere other than their company’s database or their client servers, which can increase the risk of a data breach.

Oh, the Data Breaches

Many breaches of attendees’ data occur because of human error. The security of our information is not only a technical issue; it also relies on a set of protocols and standards for anybody who has access to that data, including the company providing a technology platform and the conference organiser.

One prime example is the e-mail security vendor McAfee. In 2009, the company held a security conference at the Sydney Convention Centre. In an e-mail sent a week later thanking people for attending, McAfee added a spreadsheet containing the names, numbers, e-mail addresses, employment details and even dietary requirements of everyone who had attended. At the time, a company spokesperson said: “Due to a human error, the contact list for a seminar [held two weeks ago in Sydney] was mistakenly attached to a promotional e-mail being sent to conference delegates. This contact list included common conference registration information but did not include any financial information.”

Hostile hacks to obtain personal information may be more infrequent than breaches, but they are still an ever-present threat. For example, in 2015, it was discovered that someone had used a remote access Trojan (RAT) to access Linux Australia’s main conference database. According to Linux Australia, “the hacker installed a botnet control system on the server and, while they had access, the organisation’s conference data was dumped to disk – including the names, addresses, emails and hashed passwords of all the delegates attending its recent 'internationally renowned' conferences and events.”

7 Questions to Ask When Organising or Attending a Conference

If you organise a conference (or similar event) that human rights defenders, journalists or activists will be attending, or if you are a frequent delegate of these meetings and we want to protect personal and sensitive data, you should consider the following:

1- Collecting Data

Only collect/give personal data that is strictly necessary for carrying out a conference.

We should avoid collecting/supplying any kind of sensitive information that could reveal political affiliations, religion or information about attendees’ sexuality. In this context, it is especially important to protect information related to dietary or health restrictions, social media handles or credit card and billing information, among others.

If the conference uses electronic payment for ticket purchasing, our chances for protecting our anonymity decrease immensely: not only because processing credit-card payments requires a real ID, but also because our purchase history is very valuable for third-party profiling. Try to avoid these methods; if that’s not possible, try to choose a trusted third party for these services.

2- Secure Channels

Conference organisers should offer the option to use secure communication channels with attendees, such as encrypted emails, secure calls or encrypted chats.

- Encrypted emails (PGP). Always remember not to share personal data in the email subject (metadata is not hidden).

- Secure messaging: Signal

- Encrypted calls: Jitsi Meet

- If the conference uses a third-party company (for example a chat channel set up in a conference app) only use it if it has end-to-end encryption; if not (or we are not sure if it has it) don’t use it.

If the conference uses online forms to collect data: Enable HTTPS and avoid private companies that profile users as a business model (like Google Forms).

If there is no option to use secure communication channels, the conference organiser should reduce the amount of mandatory personal data asked for.

3- Storage of Data

The next question is where and how that data will be stored. Non-secure storage of databases is often the reason why hacking attacks are successful. A conference organiser should ensure attendees that their personal data will be protected.

“Cloud” storage A cloud is someone else’s computer. Choose storage services that can be set up in the organiser’s own server, and thus increase control over data and anonymity. A good option is Owncloud.

Encrypted files Encryption reduces risks in storing confidential data but does not eliminate it. In this context, consider using a good file encryption tool, such as VeraCrypt.

Secure access Remember: no storage is successful if our passwords are weak. Create and maintain secure passwords to access your computer, email, files and “cloud” storage service. If your email or “cloud” storage allows it, protect your account by activating two-step verification.

Location of Servers The location of the servers determines what data protection jurisdiction your information falls under.

4- Politics of Data

It is crucial to establish clear and transparent measures around how databases are accessed and maintained.

Public data about conference delegates Don’t publish any data regarding the conference attendees. If the conference wants to have a public list, inform the attendees what data will be published and wait for their explicit confirmation.

Be careful not to manage any database – especially regarding attendees’ registration – in the same website as the conference website (even if the file is not public). There are computer hacking techniques like Google Dorking that can use Google Search (and other search engines) to find security holes in website configurations and thus find, among other things, files stored on the website.

Who will have access to data and for what reasons?

Conference organisers should always restrict access to the registration database to people who really need it. They should also be able to maintain digital security measures. Likewise, conference organisers shouldn’t use this data to profile attendees without their knowledge. If a statistical analysis with registration data is needed, inform attendees and anonymise the data.

This is especially important when we use third-party services like a conference platform and/or app. As we have seen, many third parties will have access to data produced by a conference – most of them with the goal of commercialising that data. Always be aware of this: choose the conference platform that guarantees users’ privacy, and always encourage attendees to use this platform with technical measures to block third-party trackers.

5- Security checks

If the registration database will be shared with security forces to perform security checks of potential attendees, be transparent and inform them about this procedure at the moment of registration. Attendees must freely decide to continue or not with the registration.

This is especially important when the conference is hosted in countries with a low level of human rights protection: the destiny of that database is uncertain, especially in the hands of local police, so attendees need to be prevented.

6- Third-party responsibilities

If the conference organiser works with third parties such as conference apps that need to have access to the registration database, they should demand digital security measures to handle attendees’ personal and sensitive information and an overarching data-protection policy. For example, the use of HTTPS standard, encrypted communications, anonymisation of personal data, etc. They should also be clear on how this data will be used by the third parties, and if they in turn have other parties with whom they share the data.

If a third party has access to delegates’ data, please consider informing them about this and their privacy conditions; or at least give enough signs to attendees that this is a trusted third-party regarding data protection.

7- Delete databases

The first step to protecting sensitive information is to reduce how much of it we keep around. Unless the conference organiser has a good reason to store this registration database, or a particular category of information within a file, the best option is simply delete it. If that information is in emails, erase that, too.

If this information is kept, conference organisers should also set up clear and transparent protocols around that database: who will have access to it, for what reason, how long it will be kept, and with what level of digital security, including processes to anonymise the contents of that database and the removal of sensitive personal data (health, disability, ethnicity, or religion).

Alternatives

There are few-to-no alternatives that provide an answer to the needs of CSOs and activists who want to use an app for their events, especially when it is a large-scale one. And since it is a sensitive matter, it is recommended that CSOs at least give their participants the option to opt out from using apps without losing access to the event.

Crabgrass is a good tool for organisers to discuss, assign tasks, document the event and share information in private. It is a secure web-based organising tool specifically designed for activists. It can function as a social platform where you can discuss with other people, as well as organising tasks in private groups. This guide will give an overview of the options available when using Crabgrass. This is a social networking tool tailored specifically to meet the needs of bottom up grassroot organising as it has the ability to collaborate online, share files, tasks and projects. Organisers can set different groups for discussion, one for the organisers to discuss and distribute tasks and one including the participants to share updates and resources. Security in a Box has a Crabgrass guide to help you create an account and guide you in the first uses.

_ This article was written by Paz Peña and Leil-Zahra Mortada with contributions from Danja Vasiliev and Rose Regina Lawrence _

Shrinking Civil Space: A Digital Perspective

Data and Activism

Last-Minute GDPR Checklist for Civil Society Organisations

Data Baggage, Travel and Activism

What the Facebook?! To Leave or not to Leave

I Just Can't Quit You! Your Privacy Guide to Facebook

Activism on Social Media: A Curated Guide

Applying for a Visa

Booking Flights: Our Data Flies with Us

What's in Your Police File?