| When Tactical Tech’s Data and Politics research team began to investigate how personal and individual data was being utilised in modern, digitally-enhanced political campaigns, we were quickly struck by the unbalanced coverage, particularly in the media, of the methods and strategies of data acquisition, analysis and utilisation by political campaigns across countries and different political contexts. In collaboration with international partners, we produced 14 studies to identify and examine some of the key aspects and trends in the use of data and digital strategies in recent and/or upcoming elections or referendums in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Italy, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, Spain – Catalonia, the United Kingdom and the United States. By working with journalists, digital rights advocates, lawyers, academics and data scientists, our multidisciplinary and practitioner-led approach has produced contextual overviews and tangible case studies of how personal and individual data is used by political campaigns in countries across the globe. With this collection of reports, we aim to expand our understanding of these issues beyond the contemporary, global-north focused coverage. |

|---|

The results of the 2015 Canadian federal election, the longest election campaign season in living memory, saw the Liberal Party of Canada, led by Justin Trudeau, gain a majority in the House of Commons. The liberally and mainly centrally positioned party will defend its majority in the 2019 federal election, unless a sudden snap-election is called earlier.

Tactical Tech partnered with Colin J. Bennett and Robin M. Bayley to examine the role of personal data in contemporary Canadian elections and how Canadian political parties implement voter data within their election campaign strategies. Bennett is a leading scholar on the political, legal and technological ways the information society impacts personal privacy. He has been researching these questions for over 20 years at the Department of Political Science at the University of Victoria. He is currently involved in a research project on “Big Data Surveillance,” focusing on the capture of personal information by political parties. Bayley is the President at Linden Consulting, Inc. - Privacy & Policy Advisors and an expert on Canadian privacy law. She assists organisations in privacy policy and process compliance and supports regulators in developing guides and tools for organisations and the public on these topics. She is also a prolific author of reports on privacy regulation and methodologies.

Below are some select findings from our partners' report on the use of personal data in Canadian election campaigns. They cover some of the tools and strategies employed by campaigning parties, the commercial sectors supporting the data-driven ecosystem, as well as the legal frameworks governing the collection and analysis of citizen data in Canada. Further topics and in-depth details can be found in their full report.

Voter-data analytics and micro-targeting of messaging have become staple features of electoral campaigning in Canada for well over a decade:

Canada has relatively low numbers of dedicated party adherents, strict rules governing the financing of election campaigns and a focus on middle-of-the-spectrum voters.

Due to these factors, political parties pursue a strategy of “permanent” campaigning and seek increasingly detailed understandings of key district and constituency swing voter attitudes.

The perceived need for data on voters means that parties are moving into year-round campaigning in which they continue electioneering tactics and make contact with voters before, during and after election seasons.

In this vein, Canadian voters face full-spectrum campaigning where “slicing and dicing” and the tailoring and targeting of messages to individuals includes:

- campaign signs

- newspaper, radio and television advertisements

- direct contact via personal or automated phone calls and door-to-door canvassing

as well as a full range of modern digital campaigning including:

- advertisements on social media

- suggested posts or articles

- promoted links

- other digital materials

Canada’s digital political campaigning ecosystem incorporates polling, data brokering, analytics and modelling, data science, online behavioural advertising, social media outreach and consulting services:

Polling companies are increasingly adopting similar methodologies when assessing consumers' demand for products and political preferences of voters and potential voters.

Commercial data brokers have been at work in Canada for decades and have been applying their experience in collecting, analysing, cross-referencing and segmenting vast amounts of consumer information into various classifications to support political campaigns since as early as 2006.

Data analytics firms provide analytic tools and algorithmic services to political campaigns, which are used to identify patterns in data, shifts in opinions and persuadable voters. This allows them to optimise who, when, how to target voters during the campaign cycle and with what messages.

Advertising and marketing companies cater to political parties with a host of high tech, data-fuelled methods to shape the pitch and tone of the digital micro-targeted material.

While the actors and practices of the influence industry in Canada mirror those in the United States, the country’s campaign financing regulations and (to some extent) privacy laws mean the industry is not nearly as extensive or developed as it is south of the border.

Parties’ own voter databases and scoring systems are central to political campaigning:

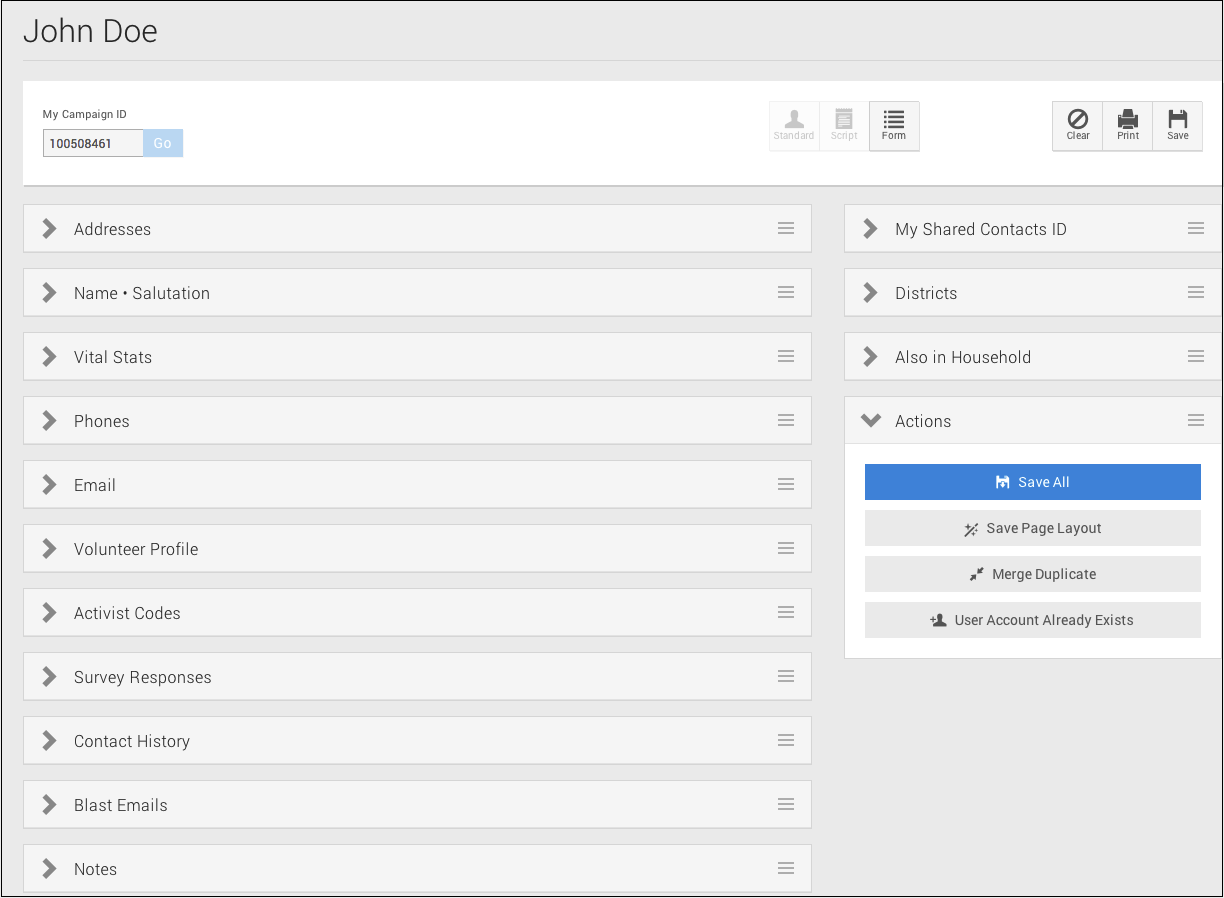

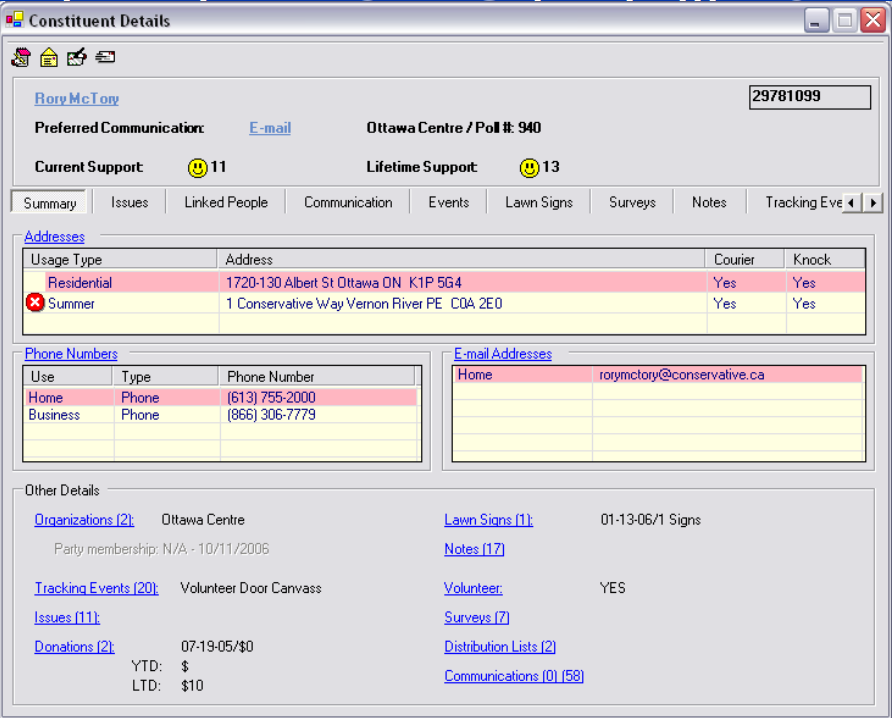

Each party maintains its own brand of customisable voter management database, often built with the help of consultants from the United States and/or campaign technology firms. These databases are iterated to new systems or versions to improve the performance of the technology.

Voters are actively scored and ranked by parties based on whether a voter has been analysed as being a supporter, non-supporter or undecided – a process which is opaque at best.

Details on what data and algorithms are used to run and maintain this voter databases and scoring systems are shrouded in considerable secrecy. As relayed by the report’s authors in personal correspondence with the NDP’s Chief Privacy Officer in 2017, requests for access to personal information have been met with refusal of disclosure based on “confidential commercial information” whose disclosure could “harm the competitive position of the organization.”

The lack of data or privacy regulations imposed on political parties means that data collection and analysis is unhindered:

Canadian political parties are not regulated under the country’s privacy protection laws and regulations, which primarily focus on public bodies or organisations involved in commercial activity, although the recent Elections Modernization Act does oblige parties to develop privacy codes of practice.

Political parties have “fallen between the cracks” of legislation which focuses largely on public bodies or commercial activity. Thus they can, for example, avoid matching their data-powered and digital systems to official guidelines regulating the uses of citizen data for outreach and electronic contact, such as the country’s Anti-Spam legislation and national “Do-Not-Call” list.

While parties do have to submit to the regulations laid out by the Elections Act, they are also entrenched and prone to collectively defend their interests and tactics against regulators who would constrain certain actions.

For the most part, individuals have no legal right to learn what information is contained in party databases, to access and correct that data, to remove themselves from these party systems, or to restrict the collection, use and disclosure of their personal data.

<th class="tg-bsv2"><span style="font-weight:bold;font-style:italic">A Short Overview of the Voter Relationship Management Systems of Canada’s Main Political Parties</span><br><br><span style="font-weight:bold">CIMS – Constituent Information Management System</span><br><br>• Developed in 2004 and used by the <span style="font-weight:bold">Conservative Party of Canada</span>, CIMS was the first centralised system for voter management in Canada.<br><br>• CIMS was designed in close collaboration with US-based consultants and based on Voter Vault software (the same software used in US Republican Party systems).<br><br>• It uses a wide range of data on voter preferences to create voter scores and strategies for door-to-door canvassing, e-mail lists, phone bank outreach and other campaigning tools.<br><br>• Its effective voter analytics operation was considered one of the reasons the Conservatives were able to out-perform the Liberal Party in 2011.<br><br><span style="font-weight:bold">POPULUS</span><br><br>• POPULUS is the <span style="font-weight:bold">New Democratic Party</span>’s third iteration of their voter management system since 2011.<br><br>• The NDP is reported to have close associations with 270 Strategies, a technology-focused campaign strategy firm founded by Jeremy Bird, the former national field director for the Obama 2012 campaign.<br><br>• NDP’s poor showing in the 2015 election was in part blamed on the poor integration between local campaigns and the party’s voter analytics.<br><br><span style="font-weight:bold">LIBERALIST</span><br><br>• A new version of LIBERALIST was born out of the <span style="font-weight:bold">Liberal Party of Canada</span>'s electoral defeat by the Conservatives in 2011.<br><br>• It is a modified version of the VoteBuilder software developed by NGP VAN, a system widely used in the Obama 2008 campaign.<br><br>• The software leverages data from the official list of registered voters (as provided to all parties by Elections Canada) as well as other sources of data (though exact details are unclear), potentially including commercial sources of voter outreach data (such as phone numbers), national statistics, inputs from party workers and polling exercise results.<br><br>• The Liberal party also has close ties with other data-driven political strategy firms and has separately faced questions regarding the role of Christopher Wylie, the whistleblower at the centre of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, in his work with the party since 2008.</th>

For more details on the above highlights, read Colin J. Bennett and Robin M. Bayley’s full report on Data Analytics in Canadian Elections here.

An introduction to the Influence Industry project can be found at The Influence Industry: The Global Business of Using Your Data in Elections and an introduction to the tools and techniques of the political data industry can be found at Tools of the Influence Industry. Similar, country-specific studies on the uses of personal data in elections can be found here, with more to be added each week.

Gary Wright is a researcher and project coordinator at Tactical Technology Collective with a history in technology & innovation in international development cooperation, as well as digital and privacy rights.

Thank you to Christy Lange and Raquel Renno for their comments and support.

Published July 13, 2018.

Data and Elections in Chile: Update from Datos Protegidos

Digital Election Trends in Uganda

Personal Data and the Influence Industry in Nigerian Elections

Data & Politics Virtual Round-table: Sub-Saharan Africa Event Report

The Advent of Targeted Political Communication Outside the Scope of Disinformation in Ukraine

The Netherlands: Digital Literacy and Tactics in Dutch Politics

France: Data Violations in Recent Elections

Brazilian Elections and the Public-Private Data Trade

Catalonia: Contested Data and the Catalan Independence Referendum

USA: American Digital Politics and the Commercial Sector

Chile: Voter Rolls and Geo-targeting

India: Digital Platforms, Technologies and Data in the 2014 and 2019 Elections

United Kingdom: Data and Democracy in the UK

Kenya: Data and Digital Election Campaigning

Colombia: Personal Data in the 2018 Legislative and Presidential Elections

Argentina: Digital Campaigns in the 2015 and 2017 Elections

Mexico: How Data Influenced Mexico's 2018 Election

Malaysia: Voter Data in the 2018 Elections

Italy: Personal Data and Political Influence