| When Tactical Tech’s Data and Politics research team began to investigate how personal and individual data was being utilised in modern, digitally-enhanced political campaigns, we were quickly struck by the unbalanced coverage, particularly in the media, of the methods and strategies of data acquisition, analysis and utilisation by political campaigns across countries and different political contexts. In collaboration with international partners, we produced 14 studies to identify and examine some of the key aspects and trends in the use of data and digital strategies in recent and/or upcoming elections or referendums in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Italy, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, Spain – Catalonia, the United Kingdom and the United States. By working with journalists, digital rights advocates, lawyers, academics and data scientists, our multidisciplinary and practitioner-led approach has produced contextual overviews and tangible case studies of how personal and individual data is used by political campaigns in countries across the globe. With this collection of reports, we aim to expand our understanding of these issues beyond the contemporary, global-north focused coverage. |

|---|

The 2014 general elections in India were the largest on record, with over 800 million citizens eligible to vote in elections spread over nine phases, in what is considered the world’s largest democracy. The May 2014 result saw the most pronounced defeat for the incumbent Indian National Congress (Congress), widely regarded as centre-left, which ushered India to independence in 1947 and had dominated Indian politics since. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), frequently cited as a right-wing Hindu nationalist party, under current Prime Minister Narendra Modi managed to eke out a majority government. Congress’s performance at the polls did not qualify it as an official opposition party, leaving BJP with no formal opposition – a reflection of rising majoritarian politics against a backdrop of religious, caste, regional and class fractures in the country of 1.3 billion people.

The Indian elections have gained worldwide media attention in recent months, in particular for the role that social media has played in events in the country. In the run-up to state and other by-elections earlier this year, Congress and BJP reportedly created over 50,000 WhatsApp groups to spread campaign messages. Rumours and false information propagated through WhatsApp have instigated mobs that resulted in the killing of more than twenty innocent people since April. In one instance, a government employee hired to quell the child abduction rumours in the northeast state of Tripura was beaten and lynched. Although none of these incidents has been directly connected to campaign-created WhatsApp groups, they reflect how political and social divisions have been propagated and inflamed by digital technologies.

The 2014 general elections marked a shift in electioneering strategy, with the use of data and digital platforms occupying a central role. Experts expect that the upcoming 2019 elections will rely even more heavily on social media than those in 2014, with video content playing an even more prominent part. The increase in the use of smartphones and the expansion of 4G to rural villages has increased the number of connected users in India. About 243 million internet users, 114 million Facebook users, and 33 million Twitter users live in the country. Consequently, digital technologies and tools have become a key communication tool for political parties. As an illustration of this, reports have found that the number of tweets rose 600% from the 2009 elections to the 2014 elections.

Tactical Tech partnered with researcher Elonnai Hickok to elucidate the role played by digital platforms and personal data in India’s recent and upcoming first-past-the-post general elections in 2019, constituting the country’s 17th Parliament. Elonnai is a specialist in researching and reporting on privacy, freedom of expression, cyber security and artificial intelligence in the context of public accountability.

The section below summarises a few, major findings from Hickok’s report. Her research spans observations from news and academic articles, legislation, company websites and promotional materials, and election advertisements. More detail is available in the full report.

Although there is a growing trend toward digital and data-driven campaigning in India, the current regulatory framework for how this data can be used is not adequate. In particular, current electoral rules and media regulations do not yet fully address the use of sensitive personal data or information (SPDI) or personal information (PI), particularly in the context of elections.

The majority of data collected and used in elections in India falls outside current regulatory frameworks.

Public-sector bodies are not subject to regulations on the use of PI and SPDI. By definition, SPDI in India excludes political opinions, ethnic origins, philosophical beliefs and trade union membership – all of which qualify as sensitive personal data under the European Union’s GDPR.

In July 2018, an Expert Committee on privacy legislation drafted a bill expanding the definition of SPDI to include religious and political beliefs. The bill also extends regulations to foreign companies involved in data processing or profiling of Indian data subjects.

Political campaigns' acquisition of citizen data remains opaque. Hickok's report posits that campaigns use a combination of public data (adapted from sources like the census and voter rolls) and proprietary data (sold by a growing host of local companies offering products particularly for political campaigns).

Large-scale data collection in India has facilitated the development of companies like Germin8 Social Intelligence, which analyses social media inputs in realtime, and the widespread adoption of micro-targeting.

A plethora of foreign and domestic data and digital-services companies have been involved in India’s election campaigns, but the extent of their involvement remains unclear.

Growing connectedness in India has generated demand for digital services, which has given rise to dozens of domestic companies catering to campaigns’ needs and to contracts with foreign companies. Both SAP (based in Germany) and Oracle (based in the US) worked with the BJP in the most recent election cycle. Oracle has not publicly acknowledged its involvement.

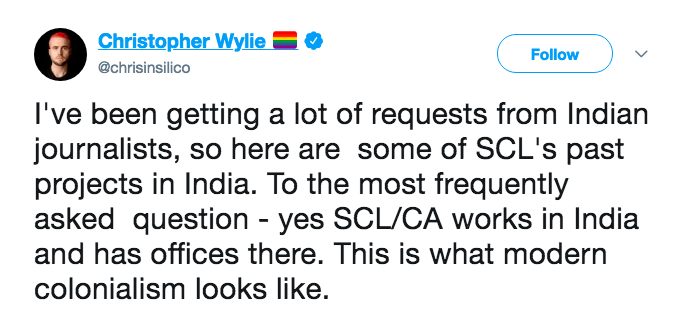

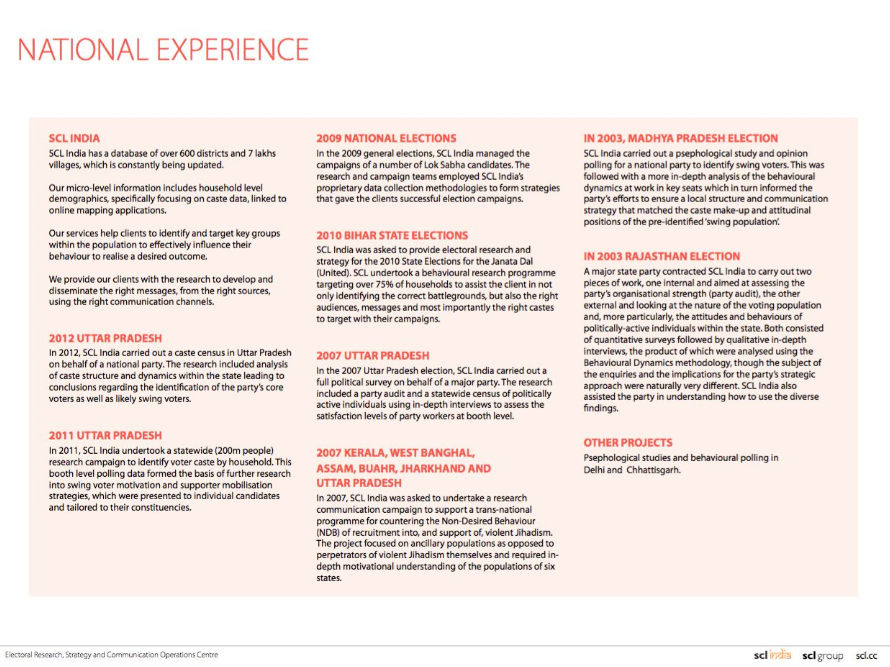

Between 2003 and 2012, Strategic Communications Laboratory (SCL) – Cambridge Analytica’s parent company – was reportedly involved in six state elections, in the 2009 national election, and others according to leaked documents from Whistleblower Christopher Wylie. The firm’s services included caste research and behavioral profiling. Though both parties deny it, SCL stated that both the BJP and Congress were clients. Furthermore, in April 2018, NDTV India displayed a copy of a pitch on data strategy for the 2019 election reportedly presented to the Congress Party by Cambridge Analytica.

Hickok’s report reveals at least four dozen domestic and international companies involved in Indian election campaigning to some degree, with short profiles accompanying select firms. One firm, Modak Analytics, claims to have amassed an electoral data repository on 814 million voters.

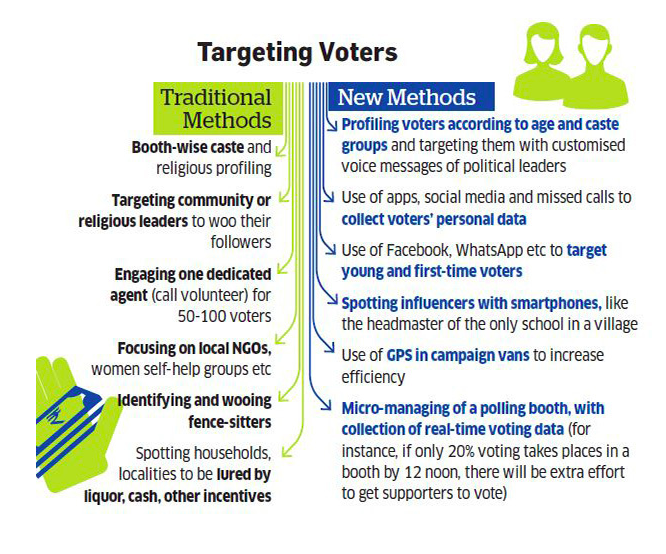

Narendra Modi’s 2014 Prime Ministerial campaign made extensive use of digital tactics, reflecting a marked change from previous campaign strategies

Modi’s campaign included a strategy dedicated to harnessing technology, data and online platforms. One component of his team was dedicated exclusively to social media analytics, and another to information technology more broadly.

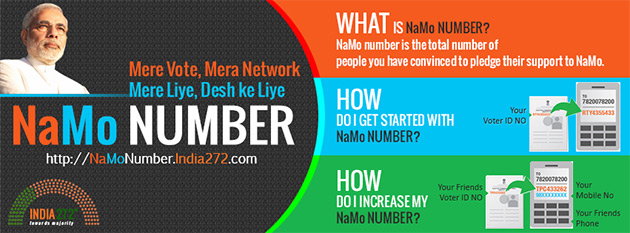

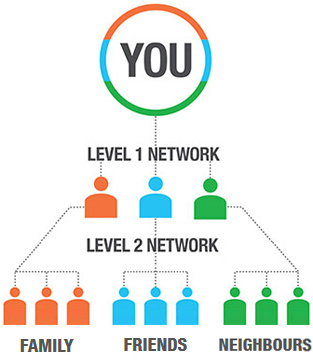

The campaign leveraged techniques such as gamification to gain new supporters during the campaign. For example, individuals were given a ‘NaMo number’ representing the number of supporters they had added – directly or indirectly, and motivating them to add more contacts (including their voter ID and phone number), with the ultimate goal of increasing the BJP supporter database. The campaign also used hologram technology to hold 1,350 3D rallies across India. Furthermore, the campaign leveraged speech-recognition start-up Voxsta – commonly called 'the political Siri' – to provide followers and potential supporters access to Modi's speeches on specific issues simply by calling a phone number.

Other tactics included installing GPS in campaign vehicles to ensure outreach to rural areas, using cookies as a data-harvesting technique for targeted ads on campaign websites, and broadcasting “Chai pe Charcha” (Discussion over Tea) conversations via satellite, internet and mobile technology in select villages as a means of putting Modi directly in touch with voters. After Modi’s first 100 days in office, Twitter published a “Twiplomacy” blog highlighting Modi’s novel use of Twitter in his communications. As one specialist observed, “Modi is perhaps one of the most tech-savvy politicians in the world and certainly the most active in India.”

For more information on the way digital tools were leveraged in Indian elections, see Elonnai Hickok’s full report here.

An introduction to the Influence Industry project can be found at The Influence Industry: The Global Business of Using Your Data in Elections and an introduction to the tools and techniques of the political data industry can be found at Tools of the Influence Industry. Similar, country-specific studies on the uses of personal data in elections can be found here, with more to be added each week.

Varoon Bashyakarla is a data scientist and researcher at the Tactical Technology Collective. His past statistical undertakings led him to a variety of domains: public health, public safety, sports, finance, and cybersecurity. After working as a data scientist in Silicon Valley, he is now living in Berlin and exploring how personal information is used for political influence.

A big, special thank you to Christy Lange for her insightful edits, suggestions, and assistance revising this piece over several rounds. Thanks as well to Gary Wright and Elonnai Hickok for their editorial guidance and to Sasha Gubskaya for getting it online to share with others.

Published August 24, 2018.

Data and Elections in Chile: Update from Datos Protegidos

Digital Election Trends in Uganda

Personal Data and the Influence Industry in Nigerian Elections

Data & Politics Virtual Round-table: Sub-Saharan Africa Event Report

The Advent of Targeted Political Communication Outside the Scope of Disinformation in Ukraine

The Netherlands: Digital Literacy and Tactics in Dutch Politics

France: Data Violations in Recent Elections

Brazilian Elections and the Public-Private Data Trade

Catalonia: Contested Data and the Catalan Independence Referendum

USA: American Digital Politics and the Commercial Sector

Chile: Voter Rolls and Geo-targeting

United Kingdom: Data and Democracy in the UK

Kenya: Data and Digital Election Campaigning

Colombia: Personal Data in the 2018 Legislative and Presidential Elections

Argentina: Digital Campaigns in the 2015 and 2017 Elections

Canada: Data Analytics in Canadian Elections

Mexico: How Data Influenced Mexico's 2018 Election

Malaysia: Voter Data in the 2018 Elections

Italy: Personal Data and Political Influence