| When Tactical Tech’s Data and Politics research team began to investigate how personal and individual data is being utilised in modern, digitally-enhanced political campaigns, we were quickly struck by the unbalanced coverage, particularly in the media, of the methods and strategies of data acquisition, analysis and utilisation by political campaigns across countries and different political contexts. In collaboration with international partners, we produced 14 studies to identify and examine some of the key aspects and trends in the use of data and digital strategies in recent and/or upcoming elections or referendums in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Italy, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, Spain – Catalonia, the United Kingdom and the United States. By working with journalists, digital rights advocates, lawyers, academics and data scientists, our multidisciplinary and practitioner-led approach has produced contextual overviews and tangible case studies of how personal and individual data is used by political campaigns in countries across the globe. With this collection of reports, we aim to expand our understanding of these issues beyond the contemporary, global-north focused coverage. |

|---|

The recent 2017 presidential and parliamentary elections in Chile saw candidates making use of personal data and data-driven campaign techniques. The implementation of a new proportional electoral system changed the rules of representation, opening up the possibility for new political parties and alliances to enter the Congress, beyond the two great coalitions that had dominated national politics since 1989. The new system increases the number of Senators and Representatives and is intended to encourage and increase voter participation. It also changes the balance of political power and has made institutions rethink ways of maintaining or extending their influence.

Fundación Datos Protegidos partnered with Tactical Tech to investigate the role of data-driven campaigning in Chilean elections. Datos Protegidos is a non-profit organisation based in Chile that works with research, education, advocacy and policy on the right to privacy and the protection of personal data as fundamental rights.

With 84% of the population online, Chile is the most connected country in Latin America. A 2016 study showed that WhatsApp is used by 86% of the national population, and Facebook by 81%. As Datos Protegidos's report notes, "the high connectivity of the country together with the massive penetration of social networks in the Chilean population make it an ecosystem conducive to using social networks as tools for political propaganda." Their report makes use of analysis of the personal data in the electoral registry, FOIA requests to the Servicio Electoral de Chile (SERVEL, the Chilean electoral service), and interviews with stakeholders and experts in the growing data-driven campaigning industry. Below are a few key findings about the use of personal data in Chilean political campaigns. More details are contained in the full report (in Spanish).

Although Chilean law prohibits the use of the country's national electoral register – which is easily accessible and considered "public information" – for commercial purposes, it is clear that it is being used for data-driven campaigning.

Chile was the first country in Latin America to legislate the protection of personal data in 1999; however, the data protection law is rarely complied with, and does not account for how personal data is used in elections.

Namely, SERVEL considers the electoral roll to be "public information," and, under transparency law, it is now fully accessible to third parties – published online in a PDF format and available in print for only the cost of reproduction.

This voter roll contains information about every Chilean over 17 years old – including their names and surnames, their unique national roll numbers, sex, and electoral address which indicates where they vote.

There is an express rule in the electoral law that prohibits the use of the voter roll for commercial purposes, with penalties ranging from a fine of one to three tax units monthly to minor prison time.

The publication of the electoral roll as a PDF has been the subject of controversy by citizens and some political sectors, who feel that its publication by the State violates their right to privacy.

According to Datos Protegidos’s research, which included interviews with experts in the field, the data in the electoral register, combined with data from other sources, is widely used for commercial purposes despite the regulations against such use – including to facilitate geo-targeting, profiling and segmentation of voters.

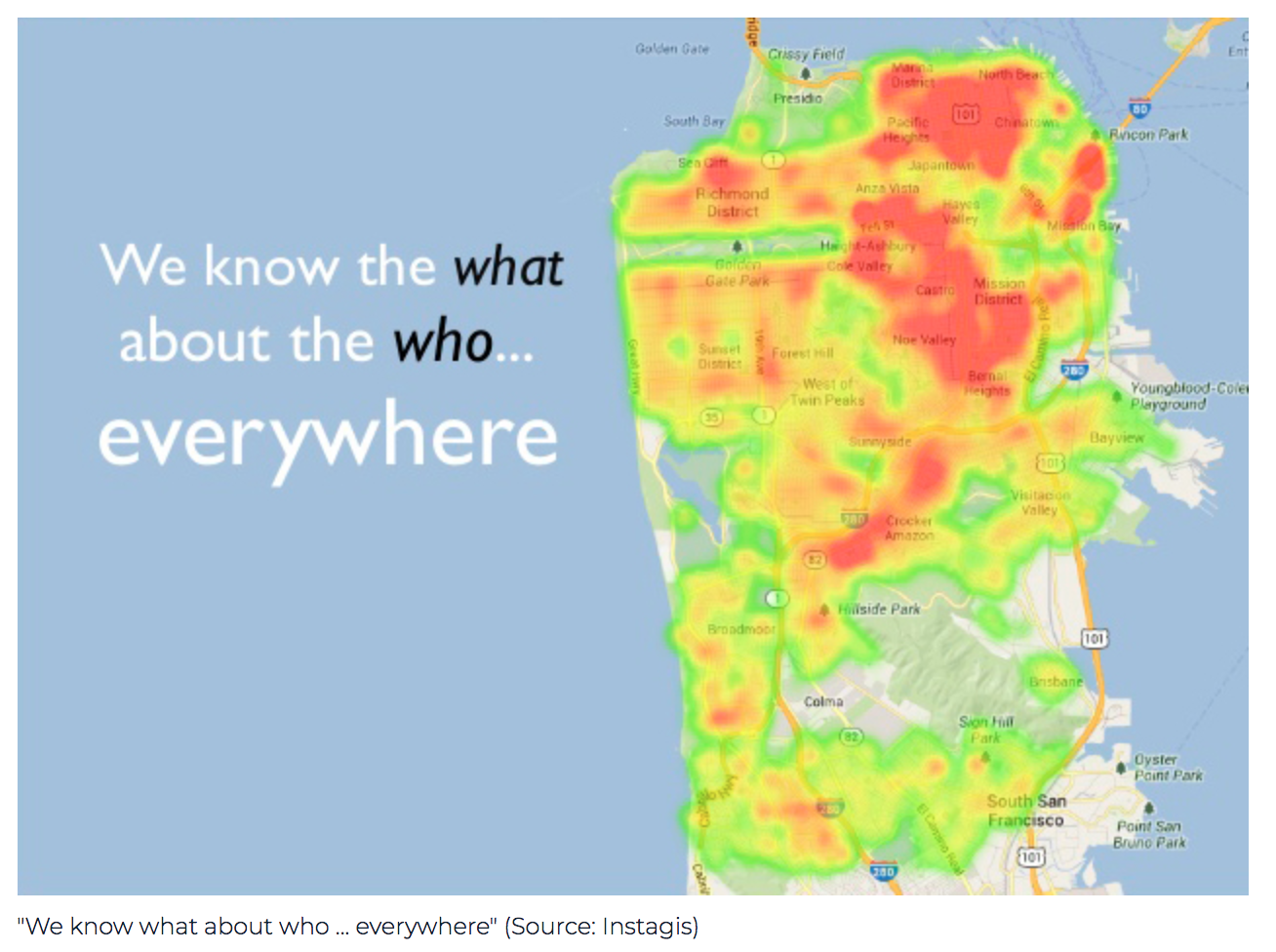

| Voter Profiling and Geo-Targeting in Chile: The Case of InstaGIS • The use of personal data in electoral campaigns is a response to a growing industry; Datos Protegidos identified at least 10 companies in Chile that design electoral campaign strategies through the use of personal data. • The largest of these companies is InstaGIS, which supported the successful election of the current president, Sebastián Piñera, and whose [services](https://www.instagis.com/en/) allow their clients "to discover the geolocation of voters, their socioeconomic status and political preferences." • According to an [article](http://www2.latercera.com/noticia/pinera-viaje-al-corazon-de-su-triunfo/) in the national newspaper La Tercera, Piñera's campaign worked with InstaGIS to "understand the voters" by analysing their comments and likes on social networks – in particular on Facebook – targeting their location, segmenting them into three groups according to their likeliness to vote for Piñera, then sending each group targeted messages and advertisements accordingly. • Another [**report**](https://ciperchile.cl/2018/01/03/instagis-el-gran-hermano-de-las-campanas-politicas-financiado-por-corfo/) by Centro de Investigación e Información Periodística (CIPER) found that InstaGIS worked with Renovación Nacional (RN, Piñera’s political party) to "cross-reference different databases with user information in social networks in order to predict patterns of behaviour, consumption and even political preferences." As the article explains, "So, every time you interact on your Facebook, Twitter or Instagram account, one of the Instagis 'bots' can monitor that content and then cross the information with your RUT [Chilean national ID] and address. Although these are considered personal data that should be protected, legal gaps mean that in practice this is not the case. The result: a geo-referenced map with information about a municipality's political leanings, where crimes are concentrated, or whether or not you are a fan of pizza or sushi." • A [contract](http://transparencia.rn.cl/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/01.-Intagis-SPA.pdf) signed by InstaGIS and RN, describes the company's services as voter profiling "based on the public electoral information available at the date of the contract and the revealed political interactions publicly on Facebook." This implies that voters are being profiled based on data in the electoral roll, geolocation of voters on social media and data about their income. This would seem to violate the condition that the electoral roll cannot be used 'for commercial purposes'. One of the outputs can be seen below: • *Datos Protegidos was not able to find evidence of a contract or agreement between InstaGIS (which is registered in Delaware, USA) and Facebook that would allow InstaGIS to extract data directly from the platform, the way Cambridge Analytica allegedly did. However, the company has [publicly declared](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7lTvWBRe8Zs) that they have investors such as Google, 500 Startups and Invesco.* • *Datos Protegidos found major discrepancies between the amounts the candidates declared on digital services – including InstaGIS – in the forms obtained through their FOIA request and the expense reports that campaigns were later required to submit to SERVEL. For example, in the original form, Piñera's campaign declared an expense of nearly 5 million Chilean Pesos (about $7,800 US dollars) on digital propaganda. However, the official SERVEL documents reveal that his campaign spent at least 30 million pesos (about $50,000 US dollars) for the InstaGIS software license alone.* |

|---|

Before the 2017 elections, the government made considerable efforts to reform electoral laws and increase transparency about campaign activity and spending. However, these reforms did not address digital media, which left the rules of digital political advertising highly ambiguous.

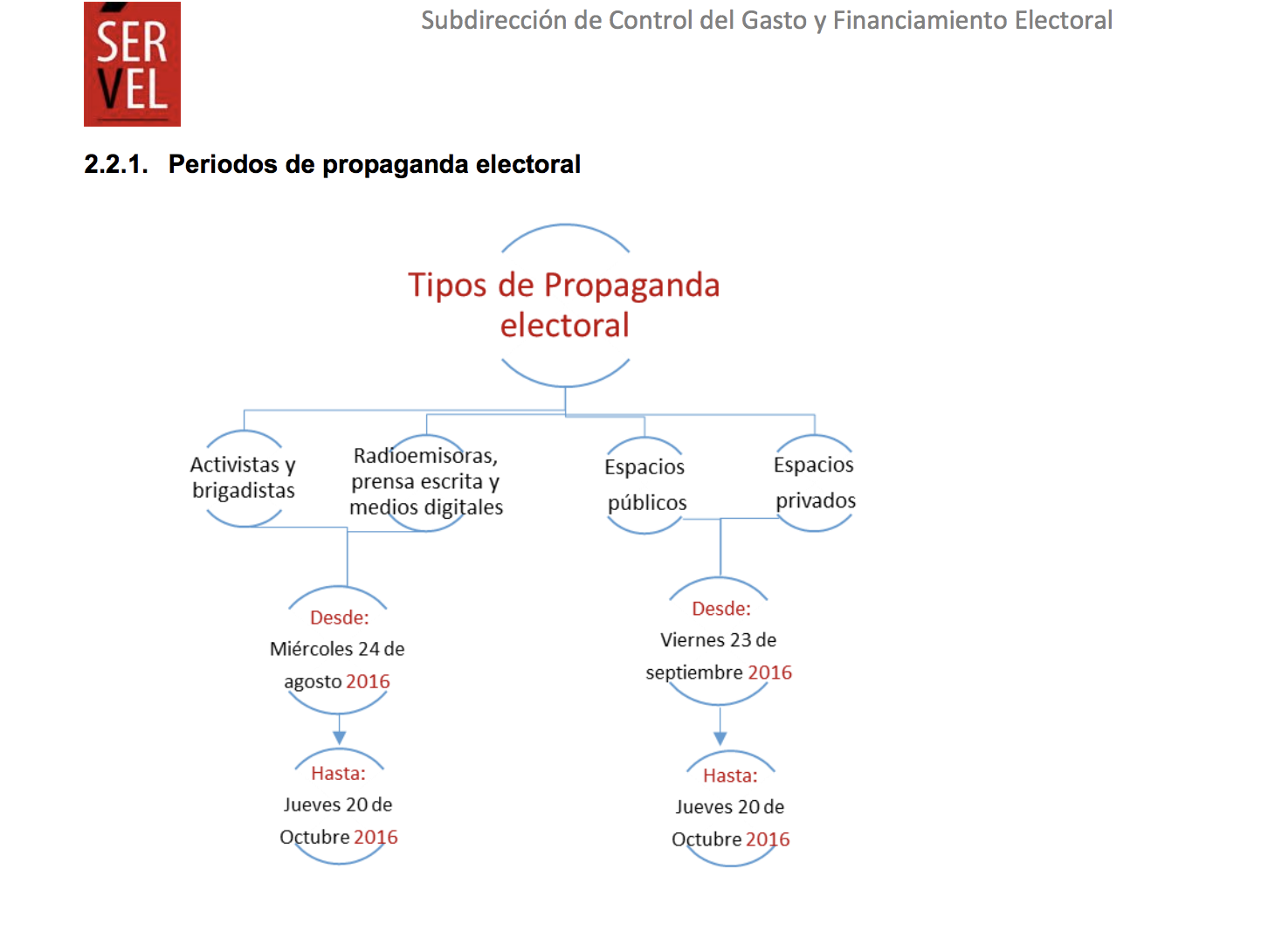

- The reforms of electoral laws established exhaustive new regulations on electoral advertising (which in Chile is referred to as propaganda electoral) for traditional media, including "any event or public manifestation and radio advertising, written, in images, in audiovisual media or other analogous tools". But the law made no specifications regarding advertising on digital media.

Initially, SERVEL (the Chilean Electoral Service) stated that campaigning on social networks was forbidden, a move that political parties openly opposed and which the Board of Directors eventually reconsidered. SERVEL then published a manual defining the terms of electoral communications and expenditures. It determines that communications through "social networks, emails and telephone calls" are "private communications" and therefore not considered 'electoral propaganda' – as long as they do not involve hiring a service to provide or obtain additional contacts. In addition, political parties must declare in writing if they use social networks, and if so, how.

Datos Protegidos made a FOIA request to SERVEL for the mandatory declarations on digital media contracted for campaign purposes. SERVEL informed Datos Protegidos that only two candidates had submitted the form declaring their respective advertising expenses: Sebastián Piñera (the current President) and the candidate Beatriz Sánchez. The first declared an expense of 4,741,201 Chilean Pesos, about $7,810 US dollars, while Sánchez declared 946,647 CLP, about $1,500 US dollars.

In interviews with industry experts that Datos Protegidos conducted for the report, they found that there are diffuse boundaries between the use of data for research purposes and commercial uses.

- As their report notes: "In Chile, it is striking how some of the companies that were identified in the profiling and segmentation business for electoral intelligence are linked to academic spaces, where it is difficult to determine [how the information is used] or exploited. Indeed, the experience of Cambridge Analytica and its connection with the research previously carried out at the University of Cambridge are dangerous alliances and that raises questions about the limits of the lawful and ethical use of data for research and scientific purposes versus the commercial purposes."

For more details on the above highlights, read Datos Protegidos's full report on digital campaigning during Chilean elections here (in Spanish).

An introduction to the Influence Industry project can be found at The Influence Industry: The Global Business of Using Your Data in Elections and an introduction to the tools and techniques of the political data industry can be found at Tools of the Influence Industry. Similar, country-specific studies on the uses of personal data in elections can be found here, with more to be added each week.

Raquel Rennó is a researcher from Latin America and Our Data Our Selves project lead at Tactical Technology Collective with a background in opinion polling and marketing research.

Thank you to Christy Lange, Stephanie Hankey, and Gary Wright for their discerning comments.

Published September 3, 2018.

Data and Elections in Chile: Update from Datos Protegidos

Digital Election Trends in Uganda

Personal Data and the Influence Industry in Nigerian Elections

Data & Politics Virtual Round-table: Sub-Saharan Africa Event Report

The Advent of Targeted Political Communication Outside the Scope of Disinformation in Ukraine

The Netherlands: Digital Literacy and Tactics in Dutch Politics

France: Data Violations in Recent Elections

Brazilian Elections and the Public-Private Data Trade

Catalonia: Contested Data and the Catalan Independence Referendum

USA: American Digital Politics and the Commercial Sector

India: Digital Platforms, Technologies and Data in the 2014 and 2019 Elections

United Kingdom: Data and Democracy in the UK

Kenya: Data and Digital Election Campaigning

Colombia: Personal Data in the 2018 Legislative and Presidential Elections

Argentina: Digital Campaigns in the 2015 and 2017 Elections

Canada: Data Analytics in Canadian Elections

Mexico: How Data Influenced Mexico's 2018 Election

Malaysia: Voter Data in the 2018 Elections

Italy: Personal Data and Political Influence