| When Tactical Tech’s Data and Politics research team began to investigate how personal and individual data was being utilised in modern, digitally-enhanced political campaigns, we were quickly struck by the unbalanced coverage, particularly in the media, of the methods and strategies of data acquisition, analysis and utilisation by political campaigns across countries and different political contexts. In collaboration with international partners, we produced 14 studies to identify and examine some of the key aspects and trends in the use of data and digital strategies in recent and/or upcoming elections or referendums in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Italy, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, Spain – Catalonia, the United Kingdom and the United States. By working with journalists, digital rights advocates, lawyers, academics and data scientists, our multidisciplinary and practitioner-led approach has produced contextual overviews and tangible case studies of how personal and individual data is used by political campaigns in countries across the globe. With this collection of reports, we aim to expand our understanding of these issues beyond the contemporary, global-north focused coverage. |

|---|

The 2017 French presidential elections, held in April and May, took place under exceptional circumstances. France was still in a state of emergency following the November 2015 Paris attacks that resulted in the death of 130 civilians. For the first time since 2002, a candidate from the right-wing National Front party advanced past the first round of elections. Not only did the eligible incumbent President – François Hollande – decide not to seek re-election, but both traditional left and right parties failed to advance to the second, run-off election, the first case of either instance since the start of France’s Fifth Republic in 1958. The contest between National Front candidate Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron of the centrist party En Marche! resulted in a victory for Macron, who won 66% of the vote.

The election marked the advent of the use of digital tactics in French politics. In the words of one expert, “the 2017 presidential and the legislative campaign was […] the year that methodical, precise political targeting arrived in France.” France’s history of strict data protections even prior to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, which took effect in May 2018, made this digital-first campaign even more noteworthy. Although French law did, and still does, accommodate certain forms of political targeting facilitated by voter lists complete with voters’ names, addresses, birthdates, and birth places, pre-GDPR French laws concerning political targeting were, in particular, especially protective. They forbade the creation of lists of citizens according to political, religious/philosophical beliefs, racial/ethnic origins, affiliations with trade unions, and aspects of health/sexual life. These restrictions are partly attributable to the Vichy Regime – the government of France between July 1940 and August 1944 – and its collection of data on religion and ethnicity as part of its “Jew file,” whereby then-head of state Marshal Philippe Pétian, without any decree from Nazi Germany, implemented a series of statutes stripping Jews of their rights. In total, 76,000 Jews were deported from France to concentration camps.

For our report on the use of data in the French elections, Tactical Tech partnered with Judith Duportail, a freelance journalist who frequently writes on freedom, love, and the role technology plays in mediating the two. Her past work explores how Facebook delivers targeted advertising, how smartphones are changing our thinking, and how Tinder alters interactions between people. Her writings in English and French have appeared in The Guardian, Aeon, Slate, Philosophie Magazine, Le Temps and Les Inrockuptibles.

A selection of findings from Duportail’s full report is below. The text encompasses themes from France’s strict history of data protection, legal shortcomings, ambiguities, broken laws in political campaigning and a closer look at how political actors are circumventing regulations. Duportail conducted original interviews as part of her reporting. Further details are available in the full report here.

Despite strict laws and data handling instructions in France, these protections have, in some notable cases, proved ineffective and ambiguous for the citizens they intend to safeguard.

France’s data protection office (CNIL) allows political organisations to store, collect and use personal information only on consenting supporters or on “regular contacts.” In terms of social media, regular contacts are defined as those who “follow a candidate on Facebook, [are] a friend with the politician on Facebook,” or have in some other capacity demonstrated a desire to maintain contact with a party or candidate. CNIL defends this classification because voters’ political affiliations cannot be ascertained from the parties/candidates with whom they are regular contacts. Critics, however, claim the policy is inadequate. In the words of one specialist, “Did citizens know that when they followed a candidate on Twitter that you allow them to collect your personal data?”

The American political campaigning software company NationBuilder, used by three presidential candidates, deactivated a data collection feature that failed to comply with the CNIL’s directives seven weeks before the elections. The “match” feature, which is normally enabled by default, enables campaigns to cross-reference information on voters’ public Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Meetup.com accounts to emails when an email address is provided to a campaign website (to, for example, subscribe to a candidate’s newsletter) and to integrate data from any internet user who has liked one of the campaign’s Facebook or Twitter posts. In some cases, the users’s location and bio, as provided in the accounts, are also stored. NationBuilder is reported to have assisted its clients in purging the improperly harvested data, whose size remains unknown.

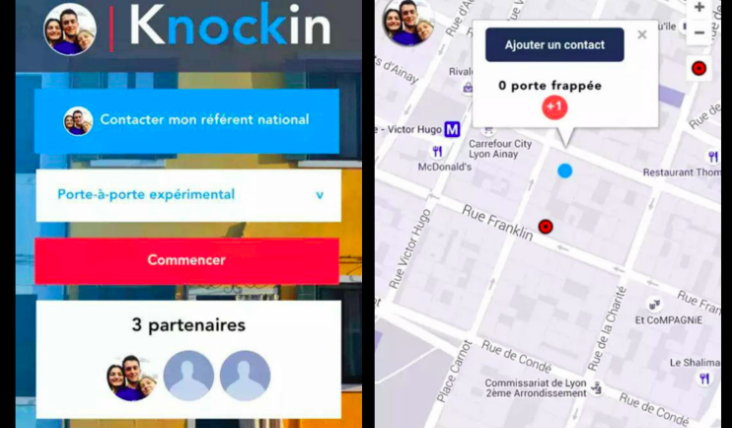

In November 2016, CNIL investigated Knockin, an app developed and used by then-presidential candidate Nicolas Sarkozy’s primary campaign. The app identified and geolocated Sarkozy supporters for door-to-door campaigning. Canvassers then visited voters’ homes on the app’s map and addressed them by name, which voters found invasive. An investigation revealed that, unbeknownst to voters, simply liking Sarkozy’s Facebook page or one of his posts on Twitter qualified the voter as a “regular contact,” thus allowing the campaign to harvest the voter’s public data (voter rolls, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc.). Despite this, CNIL still declared the app legal before later stating that combining data on voters from different sources cannot be done without consent.

The most recent election cycle included a number of violations of French data protections and several cases of mishandled data.

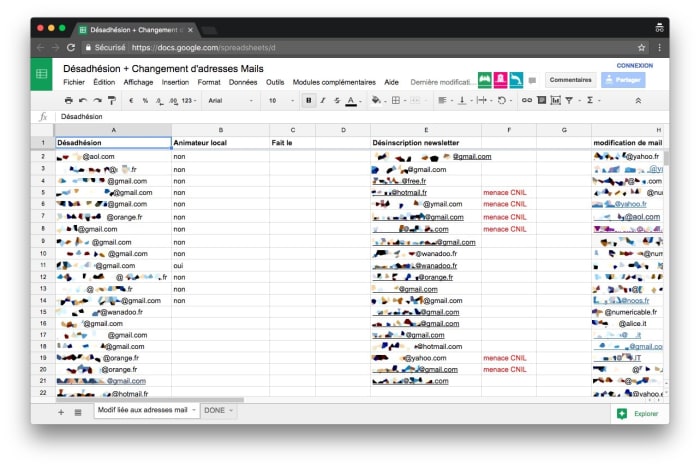

An investigative journalist found that requests to unsubscribe from Macron’s En Marche mailing list were stored in a publicly accessible Google spreadsheet. The document contained 1,000 names, email addresses and even information on whether the voter threatened to contact CNIL. This practice violated Article 34 of French law mandating that personal data be stored securely and inaccessibly from third-parties.

None of the eleven 2017 presidential campaign websites were legally sound. An analysis conducted by a researcher at Angers University concluded that none respected CNIL’s requirements: informing visitors of the use of cookies, soliciting users for consent, and offering users the possibility to contest the use of cookies. Six candidate websites failed to fulfil any of these three legal obligations.

The same study found that nine candidates’ websites used Google Analytics without offering visitors the option to share their data with Google anonymously. While using Google Analytics is not illegal, investigations into presidential campaign websites calls into question the sincerity of candidates’ claims to protect French citizens’ data, while failing to respect the law on their own websites. These findings on campaign websites were published days before the first round of elections. When asked about investigating the matter further, CNIL explained that launching an inquiry at the time was impractical because results would only be finalised after the election.

French laws designed to prohibit individual-level targeting are circumvented by services like those provided by Paris-based firm Liegey Muller Pons, which aggregates personal data. Such services are no less data-intensive than those unconstrained by such legal requirements.

| • Liegey Muller Pons (LMP) is a digital campaigning firm that has provided services to over 1,000 campaigns across six European countries. French law prohibits individual-level targeting except under select circumstances. As one expert commented, “political parties, to bypass CNIL legislation, don’t do individual targeting but polling station or district targeting.” LMP offers its French clients information on which polling districts to prioritize for door-to-door campaigning operations based on which are thought to be more amenable to the candidate’s ideas. • In the words of LMP’s Head of Product: “We produce analysis combining public open data from Insee (The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies) and election results [...]We built a database for every polling station in France (there are 65,000 polling stations in France) combining election results since 2007 and a hundred different socio-demographic variables such as unemployment rate, youth unemployment rate, average time spent in public transport every day, average incomes, average number of children or marital status, etc. Using this database, we are able to produce a statistical analysis to give a level of priority to a district.” • To assist with mapping France’s 65,000 polling stations, LMP forged a partnership with Cloud Factory, a Nepalese data processing company. As explained in a blog post, Cloud Factory states that it helps LMP “accurately visualize households within a geographic location, including their political proclivities.” Cloud Factory states it takes “huge amounts of complex information, such as family size, socio-economic indicators, political affiliations, and other public data, and visualize it in an interactive map” for LMP. • Though LMP claims to never use personal data, volunteers on the ground still apparently take notes on their interactions with people, what questions were raised, how they may be reached (e.g., name and email). Even when this information is later anonymised, it is still a component of their work, despite their claims.  |

|---|

An introduction to the Influence Industry project can be found at The Influence Industry: The Global Business of Using Your Data in Elections and an introduction to the tools and techniques of the political data industry can be found at Tools of the Influence Industry. Similar, country-specific studies on the uses of personal data in elections can be found here.

Varoon Bashyakarla is a data scientist and researcher at the Tactical Technology Collective. His past statistical undertakings led him to a variety of domains: public health, public safety, sports, finance, and cybersecurity. After working as a data scientist in Silicon Valley, he is now living in Berlin and exploring how personal information is used for political influence.

Thank you to Christy Lange for her discerning comments and to Safa Ghnaim for assistance with posting this piece online.

Published December 7, 2018.

Data and Elections in Chile: Update from Datos Protegidos

Digital Election Trends in Uganda

Personal Data and the Influence Industry in Nigerian Elections

Data & Politics Virtual Round-table: Sub-Saharan Africa Event Report

The Advent of Targeted Political Communication Outside the Scope of Disinformation in Ukraine

The Netherlands: Digital Literacy and Tactics in Dutch Politics

Brazilian Elections and the Public-Private Data Trade

Catalonia: Contested Data and the Catalan Independence Referendum

USA: American Digital Politics and the Commercial Sector

Chile: Voter Rolls and Geo-targeting

India: Digital Platforms, Technologies and Data in the 2014 and 2019 Elections

United Kingdom: Data and Democracy in the UK

Kenya: Data and Digital Election Campaigning

Colombia: Personal Data in the 2018 Legislative and Presidential Elections

Argentina: Digital Campaigns in the 2015 and 2017 Elections

Canada: Data Analytics in Canadian Elections

Mexico: How Data Influenced Mexico's 2018 Election

Malaysia: Voter Data in the 2018 Elections

Italy: Personal Data and Political Influence