| When Tactical Tech’s Data and Politics research team began to investigate how personal and individual data is being utilised in modern, digitally-enhanced political campaigns, we were quickly struck by the unbalanced coverage, particularly in the media, of the methods and strategies of data acquisition, analysis and utilisation by political campaigns across countries and different political contexts. In collaboration with international partners, we produced 14 studies to identify and examine some of the key aspects and trends in the use of data and digital strategies in recent and/or upcoming elections or referendums in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Italy, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, Spain – Catalonia, the United Kingdom and the United States. By working with journalists, digital rights advocates, lawyers, academics and data scientists, our multidisciplinary and practitioner-led approach has produced contextual overviews and tangible case studies of how personal and individual data is used by political campaigns in countries across the globe. With this collection of reports, we aim to expand our understanding of these issues beyond the contemporary, global-north focused coverage. |

|---|

Until Malaysia's most recent election in May 2018, the ruling party – Barisan Nasional (BN), a race-based coalition dominated by Umno, a Malay nationalist party – had not lost a single general election since the country achieved its independence from Britain in 1957. But BN's power has been challenged in recent years. In 2008, BN lost its two-thirds majority in Parliament, and in 2013, the party lost the popular vote but remained in power due to an electoral system weighted in favour of rural, pro-BN seats.

With the party’s 61-year rule at risk and a Prime Minister entangled in controversy, Barisan Nasional exercised its exclusive access to government data on voters for campaigning purposes in the run-up to the most recent election. Nevertheless, Pakatan Harapan (PH), a centre-left coalition heading the opposition, unseated the incumbent, right-wing party in May.

Tactical Tech partnered with Boo Su-Lyn to explore the acquisition, analysis and application of personal data in the context of political campaigning in the lead-up to Malaysia’s 2018 general election. Boo is an assistant news editor and columnist with Malay Mail, a Malaysian news outlet. The Kuala Lumpur-based journalist is the author of Unapologetic, a non-fiction book that pushes the case for individual empowerment, secularism and civil liberties. Boo conducted first-hand interviews and research for this report. She has worked in the media industry since 2010 and reports regularly on national politics and current affairs in Malaysia.

A number of political developments have transpired in Malaysia since March 2018, when Boo completed her report, which renders it all the more noteworthy. A summary of these events is provided on the final page of the full report. Notably, between the 9 May general election and 23 June, 10 of BN’s 13 component parties left the coalition, leaving BN with the original three parties of its post-Independence predecessor.

Below is a collection of selected key findings from Boo’s report on personal data in Malaysian political campaigning. Her findings span historical, legal and technical boundaries in data use and encompass controversial data practices and nascent tech enterprises. Further details and additional topics can be found in her full report.

Recent data-driven campaign tactics suggest that the use of personal data may be complementing the practice of vote-buying

- Officials in charge of the 1Malaysia Development Berhad allegedly laundered more than $4.5 billion, a portion of which appeared to have been used to help the then-ruling party, BN, secure a victory in the 2013 elections.

- Polling watchdogs have observed multiple parties offering handouts/services in exchange for votes. Although these offers are illegal under the Election Offences Act, little legal action has been taken.

- An anonymous letter sent to the country’s oldest human rights group’s magazine claimed that petrol vouchers were being distributed to members of the public in the state of Penang in exchange for recipients’ names, addresses, identity card numbers, phone numbers, email addresses and employer information.

Digital tactics, underutilised in the 2013 elections, were much more widely adopted for the 2018 elections in Malaysia’s first-past-the-post electoral system

- BN’s long-running authority over TV, newspapers, radio and other mainstream media pushed opposition parties to social media as a means of circumventing government barriers. After BN lost its parliamentary supermajority in 2008 and suffered more losses in 2013, the coalition – along with other political parties – appears to have appealed to fresh, data-centric tactics in the 14th general election.

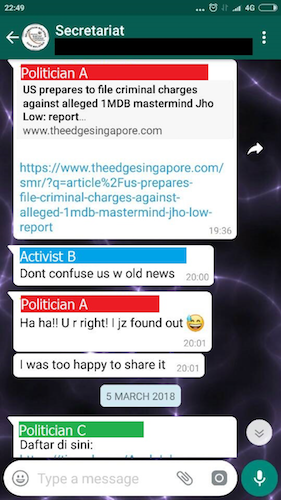

- In addition to location- and language-based micro-targeted Facebook advertisements, party representatives made extensive use of WhatsApp groups to disseminate political messages. One representative claimed to have been in 991 distinct WhatsApp groups for such purposes. Another has been sending personal birthday wishes to his supporters via SMS for the past five years.

- A host of private companies, public relations outfits and consultants, both domestic and international, have worked for Malaysian political campaigns seeking a modern digital toolkit with which to profile voters. Some companies espouse a partisan orientation and have collected sensitive information on the political stances of millions of Malaysians.

The collection of personal information by political parties has not been hindered by legal restrictions or transparency mandates

- Malaysia’s Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA), passed in 2010, was enacted to regulate the processing of personal data, but the law applies only to commercial transactions. Federal and State governments are free to amass personal data, and they are not required by law to disclose any data breaches.

- The Department of Personal Data Protection Malaysia stated that political parties collecting and using personal data for campaigning purposes does not fall within the authority of PDPA.

- These lax legal barriers appear to have facilitated BN’s ability to access and guard personal data from government sources for the 2018 general election.

- The Malaysian government is insulated from robust public scrutiny, as any Malaysian government document can be classified as a state secret per Section 2B of the Official Secrets Act (1972). In the past, these documents have included information on crime statistics and even Malaysia’s air pollution index. This has enabled the Malaysian government to collect and safeguard information with no public oversight.

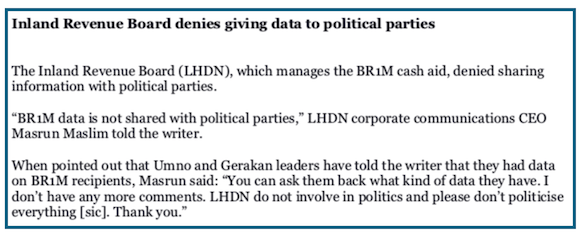

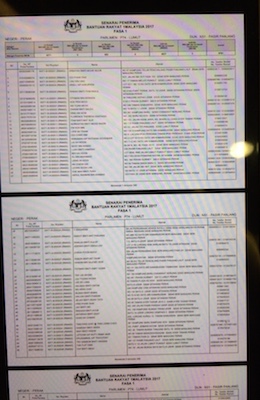

| Barisan Nasional’s access to government data and homegrown data collection efforts for political campaigning • A leader from Umno, a constituent party of the BN coalition, informed Boo that the party used personal data acquired from government agencies to convince individuals to re-elect BN by reminding them exactly how much government aid they received under the then-ruling party. Among the government agencies Umno approached are district education offices (for lists of teachers and parents), the People’s Volunteer Corps (for a list of members), other agencies (for a list of cash aid recipients), the national poverty database and others. Umno has also reported success obtaining lists of patients at public hospitals. All of this information was compiled to assess how much government aid an individual received, which was in turn communicated to the individual voter. • Despite Umno, MIC and Gerakan (all BN constituent parties) acknowledging that they had access to e-Kasih, the national poverty databank, or data on recipients of a cash aid called BR1M, a representative from the Inland Revenue Board denied any data sharing with political parties. |

|---|

For more details on the above highlights, read Boo Su-Lyn's full report on Voter Data in Malaysia's 2018 Elections here.

An introduction to the Influence Industry project can be found at The Influence Industry: The Global Business of Using Your Data in Elections and an introduction to the tools and techniques of the political data industry can be found at Tools of the Influence Industry. Additional country features on Italy and Mexico are also available.

Varoon Bashyakarla is a data scientist and researcher at the Tactical Technology Collective. His past statistical undertakings led him to a variety of domains: public health, public safety, sports, finance, and cybersecurity. After working as a data scientist in Silicon Valley, he is now living in Berlin and exploring how personal information is used for political influence.

Thank you to Boo Su-Lyn, Gary Wright, Christy Lange, and Stephanie Hankey for their suggested edits to this piece.

Published June 29, 2018

Data and Elections in Chile: Update from Datos Protegidos

Digital Election Trends in Uganda

Personal Data and the Influence Industry in Nigerian Elections

Data & Politics Virtual Round-table: Sub-Saharan Africa Event Report

The Advent of Targeted Political Communication Outside the Scope of Disinformation in Ukraine

The Netherlands: Digital Literacy and Tactics in Dutch Politics

France: Data Violations in Recent Elections

Brazilian Elections and the Public-Private Data Trade

Catalonia: Contested Data and the Catalan Independence Referendum

USA: American Digital Politics and the Commercial Sector

Chile: Voter Rolls and Geo-targeting

India: Digital Platforms, Technologies and Data in the 2014 and 2019 Elections

United Kingdom: Data and Democracy in the UK

Kenya: Data and Digital Election Campaigning

Colombia: Personal Data in the 2018 Legislative and Presidential Elections

Argentina: Digital Campaigns in the 2015 and 2017 Elections

Canada: Data Analytics in Canadian Elections

Mexico: How Data Influenced Mexico's 2018 Election

Italy: Personal Data and Political Influence