| When Tactical Tech’s Data and Politics research team began to investigate how personal and individual data was being utilised in modern, digitally-enhanced political campaigns, we were quickly struck by the unbalanced coverage, particularly in the media, of the methods and strategies of data acquisition, analysis and utilisation by political campaigns across countries and different political contexts. In collaboration with international partners, we produced 14 studies to identify and examine some of the key aspects and trends in the use of data and digital strategies in recent and/or upcoming elections or referendums in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Italy, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, Spain – Catalonia, the United Kingdom and the United States. By working with journalists, digital rights advocates, lawyers, academics and data scientists, our multidisciplinary and practitioner-led approach has produced contextual overviews and tangible case studies of how personal and individual data is used by political campaigns in countries across the globe. With this collection of reports, we aim to expand our understanding of these issues beyond the contemporary, global-north focused coverage. |

|---|

In August 2017, following a widely publicised and discussed election campaign – both off- and online, incumbent President Uhuru Kenyatta and Deputy President William Ruto (collectively referred to as Uhuruto) and their new Jubilee Party appeared to have won the bulk of parliamentary seats as well as the Kenyan presidential election with about 54% of the vote. However, former Prime Minister and opposition leader Raila Odinga and his National Super Alliance (NASA) of parties contested the presidential election results on grounds of irregularities, particularly during electronic results transmission. In an historic judgment, the Supreme Court of Kenya nullified the election, paving the way for a repeat in October 2017. NASA subsequently boycotted the re-run of the election claiming it to be an unfair process. Uhuruto won 97% of the vote with a turnout of under 34%.

In order to understand the role that personal data played in the campaigns during this election, Tactical Tech partnered with Grace Mutung’u, an Open Technology Fund Fellow at the Berkman Klein Center who specialises in freedom online and information controls in East Africa. She is also an associate at the Kenyan ICT Action Network where she carries out ICT and legal policy analysis. Below are some select findings from Grace Mutung’u’s report on the state of personal data in Kenyan election campaigns. They cover the country’s growing digitisation of the public and private sector, some of the political history of data in Kenya, how voter data is acquired and used by various actors and some features of the 2017 digital campaigning season. Further topics and in-depth details can be found in the full report.

Digital monitoring and personal data collection and analysis by the state and private sectors is well established in this highly digitised country

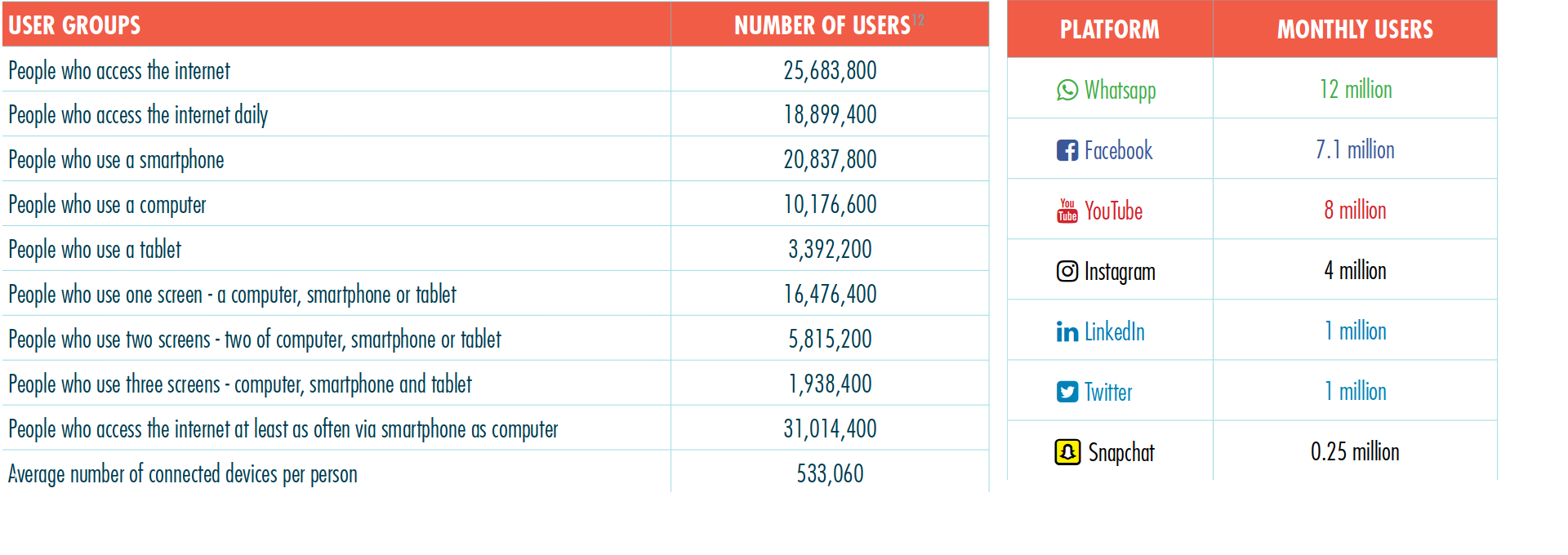

Kenya is among the continent’s most connected countries, with mobile network coverage at 75%, 25 million internet subscribers and penetration at 74.2 per 100 inhabitants. It is also a regional hub for digital start-ups and entrepreneurship. Mobile connectivity expanded beyond simple communication to include financial, address and identification services.

Private sector digital service providers, such as mobile network operators and digital start-ups, accelerate the collection and analysis of personal data through systems such as mobile financial transactions; loyalty cards and purchasing histories linked to debit cards; digital marketing and advertising; and other data-driven functions of an advancing digital innovation economy.

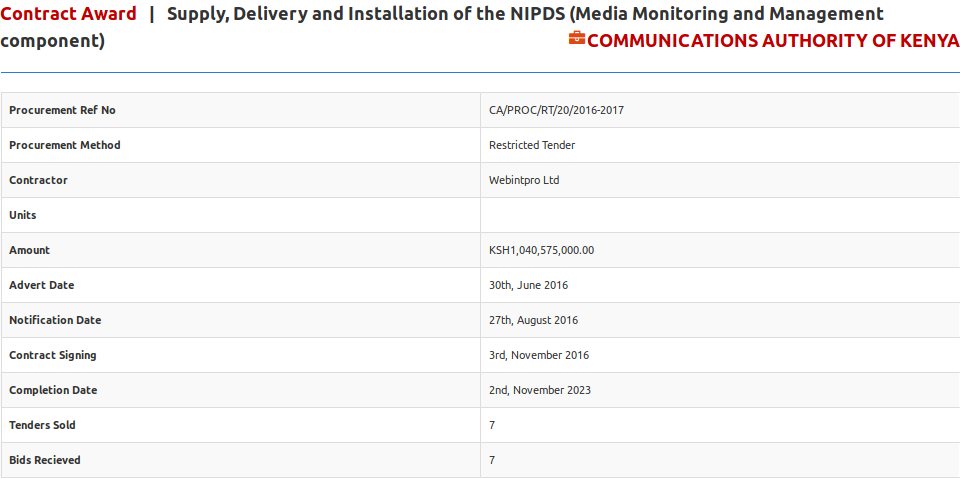

In parallel, the state has introduced a number of data-focused measures to centralise a wide range of dispersed citizen data registries and has introduced significant digital monitoring practices in response to security concerns. Following the post-election violence of 2007, where digital platforms were blamed for inciting violence, the state has invested heavily in digital surveillance systems, including hardware monitoring and social media monitoring. Digital surveillance was further expanded to support anti-terrorism operations.

Personal data and its acquisition for identification has been politicised for generations

Identification and segmentation of the population for political purposes can be traced through Kenya’s modern history. Some of the first systematic registrations of Kenyans took place during the colonial era and include the poll tax registration of black households in 1901 and the Native Registration Ordinance in 1915. This process was expanded during general census taking, which identified and demarcated tribes, clans and sub-clans and mapped them to geographic locations. These types of measures helped to establish ethnicity as the basis for demarcation of administrative areas and identification of citizens.

Today, the Registration of Persons Act requires a series of demographic and biometric data contained in an electronic card which has become the de facto ID card in everyday life. As this form of identification has become essential for life in Kenya, it has been politicised during election campaigns. For example, ID registration drives have been used to enlist new voters while registration procedures have been tactically used to block others from registering.

In the 2017 election season, voter data was sourced by multiple actors for a number of purposes

Kenya’s Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) carried out a mass voter registration exercise in early 2017 which required those wishing to register to provide their national ID number, biometric information, polling station location and phone number. While partly redacted voter registers are usually publicly published, the 2017 registers were also available for purchase by candidates and made publicly available via an online and SMS portal. Concerns were raised that sensitive ID numbers and full names were thus openly available to the wider public and, in the case of the register available online, easily susceptible to automated scraping.

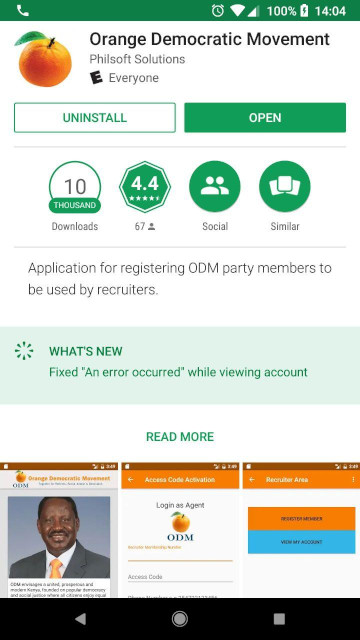

Political parties are required by law to present their party membership lists prior to elections and membership must feature a degree of diversity of ethnicity, gender, minority groups and regional representation. Data on members, such as names, dates of birth, gender, county, constituency, ward, polling station and phone numbers, is collected through various registration drives conducted by aspiring party candidates and grassroots activists, however there are significant cases where citizens have found themselves on membership lists without their consent. The main contenders in the election (Jubilee and NASA) used electronic smartcards and mobile apps to register members. Both required the sourcing of numerous pieces of personal data from new members.

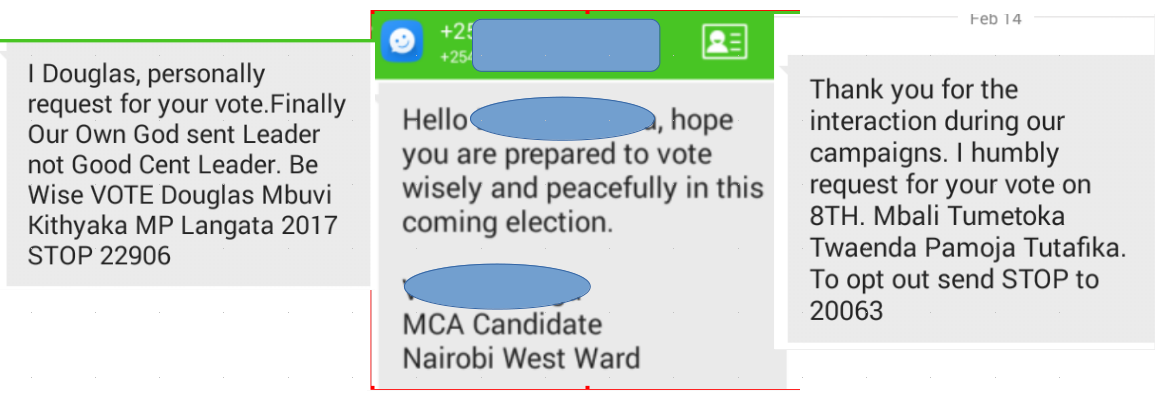

Receiving unsolicited text messages offering a range of consumer products is not uncommon in Kenya. While the country’s consumer protection regulations foresee a regulated opt-in system into these digital marketing systems, in reality unlicensed “bulk SMS agents” build and maintain contact databases as a form of commodity. Political operatives report that obtaining contact databases and bulk SMS packages from such “traders” for direct engagement with voters is a well-known practice during election seasons.

In a shift from the 2013 election, data-driven election campaigning in 2017 evolved from broader demographic targeting to more personalised approaches

Closed groups on messaging platforms such as Telegram and WhatsApp were a significant feature in 2017 and ranged from groups for core supporters, where political content and logistics were coordinated, to groups where people were added by supporters – often times without their consent.

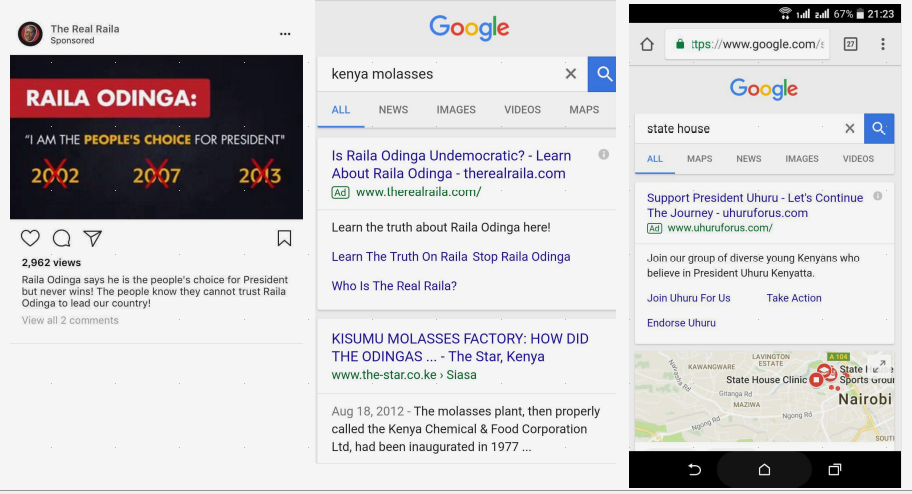

Targeted advertising on social media and search platforms was deployed by parties and candidates in a move to diversify away from traditional media strategies, such as billboards, radio, television and newspapers.

Professional digital election campaign consultants were used by all sides during the election and ranged from international firms such as Cambridge Analytica (UK), Aristotle, Inc. and Harris Media (USA) to national media and communications consultants and social media influencers. They provided services ranging from negative campaigning, to creating and spreading viral content, hashtags and memes to selected groups of supporters and voters.

<th class="tg-bsv2"><span style="font-weight:bold;font-style:italic">When state surveillance, digital platforms and data-driven campaigning collide</span><br><br>Contact-to-contact and group messaging services, such as Telegram and WhatsApp, played a central role in the 2017 election campaign. Used as a tool for both supporter coordination and a means to disseminate party propaganda, the numerous groups were also a breeding ground for the spread of memes, viral media and fake news delivered in formats and themes recognisable to Kenyan society, such as religion, sensationalism, song, sermons, story-telling, tribal languages and more.<br><br>In the final stretches of the campaign season, the National Cohesion and Integration Commission identified 21 politically-orientated WhatsApp groups for spreading hate speech. As the digital spread of hate speech was identified as a cause of the post-election violence of 2013, the NCIC and the Communications Authority renewed the guidelines on the sharing of political messages via digital outlets to cover vernacular language, tone, accuracy and accountability and placed the responsibility of enforcement on platform or group administrators.<br><br>However, there remains uncertainty as to how the NCIC identified the contents of these 21 closed and encrypted groups. While the state has access to widespread digital surveillance mechanisms, it is speculated that the information was gleaned from group infiltration or leaked by the groups’ members. </th>

For more details on the above highlights, read Grace Mutungu’s’s full report.

An introduction to the Influence Industry project can be found at The Influence Industry: The Global Business of Using Your Data in Elections and an introduction to the tools and techniques of the political data industry can be found at Tools of the Influence Industry. Similar, country-specific studies on the uses of personal data in elections can be found here, with more to be added each week.

Gary Wright is a researcher and project coordinator at Tactical Technology Collective with a history in technology & innovation in international development cooperation, as well as digital and privacy rights.

Thank you to Varoon Bashyakarla and Christy Lange for their revisions. A special thanks to Sasha Gubskaya for posting this piece online.

Published July 31, 2018.

Data and Elections in Chile: Update from Datos Protegidos

Digital Election Trends in Uganda

Personal Data and the Influence Industry in Nigerian Elections

Data & Politics Virtual Round-table: Sub-Saharan Africa Event Report

The Advent of Targeted Political Communication Outside the Scope of Disinformation in Ukraine

The Netherlands: Digital Literacy and Tactics in Dutch Politics

France: Data Violations in Recent Elections

Brazilian Elections and the Public-Private Data Trade

Catalonia: Contested Data and the Catalan Independence Referendum

USA: American Digital Politics and the Commercial Sector

Chile: Voter Rolls and Geo-targeting

India: Digital Platforms, Technologies and Data in the 2014 and 2019 Elections

United Kingdom: Data and Democracy in the UK

Colombia: Personal Data in the 2018 Legislative and Presidential Elections

Argentina: Digital Campaigns in the 2015 and 2017 Elections

Canada: Data Analytics in Canadian Elections

Mexico: How Data Influenced Mexico's 2018 Election

Malaysia: Voter Data in the 2018 Elections

Italy: Personal Data and Political Influence