| When Tactical Tech’s Data and Politics research team began to investigate how personal and individual data was being utilised in modern, digitally-enhanced political campaigns, we were quickly struck by the unbalanced coverage, particularly in the media, of the methods and strategies of data acquisition, analysis and utilisation by political campaigns across countries and different political contexts. In collaboration with international partners, we produced 14 studies to identify and examine some of the key aspects and trends in the use of data and digital strategies in recent and/or upcoming elections or referendums in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Italy, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, Spain – Catalonia, the United Kingdom and the United States. By working with journalists, digital rights advocates, lawyers, academics and data scientists, our multidisciplinary and practitioner-led approach has produced contextual overviews and tangible case studies of how personal and individual data is used by political campaigns in countries across the globe. With this collection of reports, we aim to expand our understanding of these issues beyond the contemporary, global-north focused coverage. |

|---|

Between 2015 and 2017 there have been two general elections in the United Kingdom and one referendum on whether the UK should remain part of, or leave, the European Union. During this time there have also been increasing inquiries – from media, researchers and political organisations – into the use of personal data in these political processes. One of the most prominent examples of these investigations is the 2017–2018 parliamentary hearings by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) into the impact of fake news on the political process. Among other revelations, the hearings demonstrated how widespread and normalised data-driven practices across political campaigning in the UK have become.

The hearings prompted the DCMS to release an interim report calling for “urgent actions,” including new regulations for tech companies, social media platforms and UK electoral laws, amongst other changes. In addition to extensive media reports on the Cambridge Analytica and Facebook scandal, there have been other investigations into the use of data in campaigning, including Nick Anstead’s cross-party study into the use of data in the 2015 elections; a recent investigation by the Electoral Commission; and the Constitution Society’s critical review of digital campaigning and regulatory safeguards. Despite this broad range of investigations there are fewer attempts to create an aggregate view of the use of data in elections in the UK and what can be determined from existing reports and transparency measures.

Members of Tactical Tech's Data and Elections team have undertaken extensive research in an effort to create a broader overview of the role of personal data in the 2015 and 2017 general elections and the EU referendum. The report synthesises and compares previous research, creating both a broader overview and revealing gaps or inconsistencies between accounts. It makes use of wide variety of sources, including: self-published materials by parties and campaign staff, journalistic and academic reports, and testimony from the DCMS hearings. In particular, the report performs an in-depth study and analysis of the official spending reports from the Electoral Commission, which oversees elections and regulates political finance.

Below is a summary of the three key findings presented in the full report.

Finding 1: Data-driven practices may expand the gaps between political parties

Whilst it is evident that all the parties engaged in some form of digital and data-driven campaigning across a wide range of companies, it is clear that the two parties with the largest supporter base, influence and income – the Labour Party and the Conservative Party – spend far more on data-driven campaigning. Our analysis of reported party spending in the 2017 general election revealed that the Labour Party spent two to three times more money on digital services than their next largest competitor, while the Conservative Party spent six to ten times more on data-driven campaigning.

This suggests that better-resourced political groups have more access than their competitors to tools, knowledge and services such as costly consultancies. In both the 2015 and 2017 elections, for example, the Conservative party was able to hire Jim Messina from the Messina Group, which specialises in using granular data to target precise voters in specific constituencies. Labour, meanwhile, hired the digital strategy firm Blue State Digital, who helped them transform their internal digital structure and their external digital communications to best reach voters and recruit volunteers.

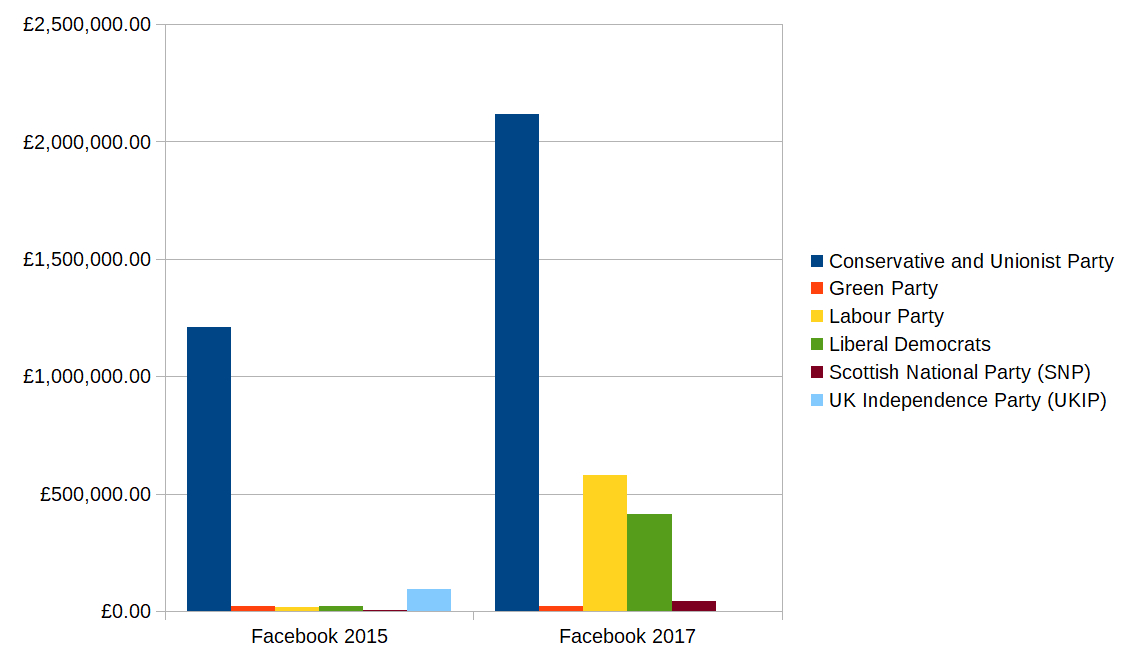

Examining and comparing party spending in 2015 and 2017 also reveals significant differences in investment in services provided by large platforms such as Google and Facebook. The chart below shows how Conservatives poured over £2 million into Facebook services in 2017 alone. We can infer that the more money that a party can spend, the more likely they are to reap the benefits that such platforms can provide. These kinds of disparities in resources likely serve to exacerbate the gaps in influence between the two largest parties and the rest of the field.

Finding 2: Parties in the UK have significantly increased their investment in data-driven campaigning since 2015

Our analysis of reports of spending to the Electoral Commission found that the amount of money invested in digital marketing tools and individual data collection practices increased substantially from 2015 to 2017 across all parties.

Conservatives spent £1 million more on data-driven campaigning in 2017 than in 2015, while the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats spent three times more from one election to the next, and the Scottish National Party spent more than fives times more over the two years.

The Electoral Commission’s research into digital campaigning shows that this rise in spending on digital campaigning companies across all campaigning groups has gone from 0.3% of total spend in 2011 to 42.8% of total spend in 2017.

From the increases in spending on these services, we can infer that there is an increased investment in the acquisition and analysis of personal data of citizens and associated methods and strategies that make use of that data, including:

increased spending on purchasing personal data such as from Experian, a company that sells data and profiles on individuals and groups, as well as companies not known for selling data, such as Labour's reported purchase of data on parents and the size of their families from Emma’s Diary, a pregnancy and childcare advice website.

increased investment in tactics leveraged through large-scale platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Google Search, who themselves collect and analyse personal data to enable targeting.

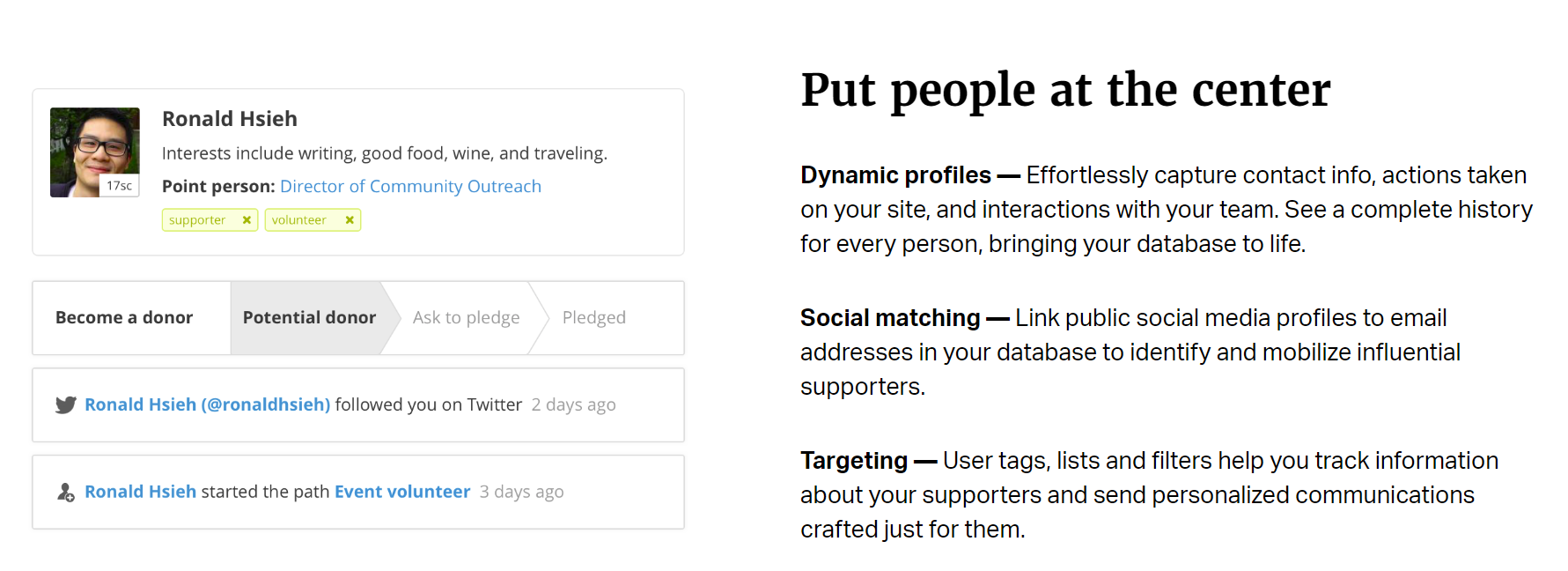

increased investment in customer relationship management systems (CRMs) – systems that manage databases of information about individuals – which can help collate a history of their interactions with a political party, divide databases into groups to send targeted emails or push certain social media messages (see Image 1).

Finding 3: Information about data-driven practices in campaigns remains opaque

- Tactical Tech's research identified several factors that make it difficult for any external evaluator, concerned citizen, researcher or even regulators such as the Electoral Commission to monitor or assess the tools and techniques of data-driven campaigning in the UK. The key challenges outlined in the report include:

A lack of transparency and consistency amongst those who use personal data in political campaigns: The full report outlines a variety of examples of inconsistency in reports, including conflicting testimonies in the DCMS hearings by the former CEO of Cambridge Analytica Alexander Nix, and Leave.EU's biggest donor Arron Banks.

Difficulties in monitoring and creating transparency in political data-driven advertising: In some cases, only the platforms that publish an advertisement or the purchaser of the ad know its intended audience. At the time of writing, efforts to make these types of targeted ads transparent are ongoing and have met with varying degrees of success, but they did not exist during the 2015 and 2017 elections campaigns or during the EU referendum.

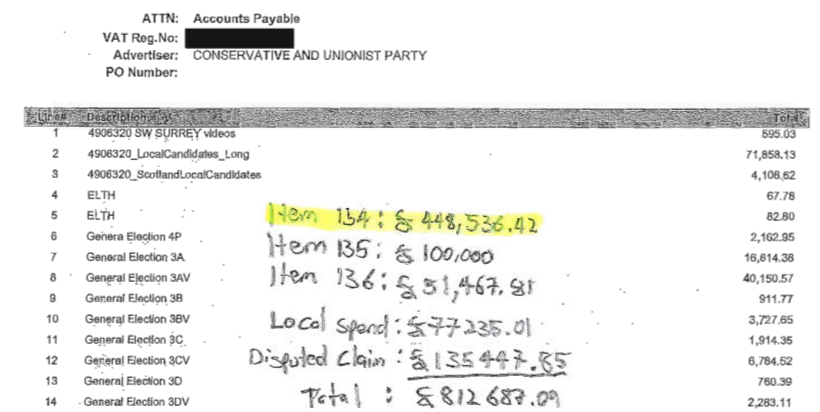

Inherent challenges within the existing expense reporting regime of the Electoral Commission: The system requires invoices to be submitted for all campaigning groups during a reporting period of an election or referendum. However, the submitted expenses and invoices make it difficult to ascertain accurate spending amounts, which are made more opaque by the use of third-party intermediaries, less-than-transparent reporting, and loopholes in the system.

An invoice showing a payment from the Conservative Party to Facebook (Image 2), for example, shows how difficult it can be to decipher exactly how money was spent and on which services if reporting is not fully transparent.

Personal data has become integral to campaigning in the UK, and is bound to become even more so. The use of data-driven campaigning has effects on the access to, and quality of, information the electorate have as well as the success of different parties. In order to assess the impacts of these practices, it is necessary to have accessible transparency of decision making, spending and implementation. For more details about the use of personal data in the democratic process in the UK, see Tactical Tech's full report.

An introduction to the Influence Industry project can be found at The Influence Industry: The Global Business of Using Your Data in Elections and an introduction to the tools and techniques of the political data industry can be found at Tools of the Influence Industry. Similar, country-specific studies on the uses of personal data in elections can be found here, with more to be added each week.

Amber Macintyre is a freelance researcher in campaigning and technology. She is currently working on the ourdataourselves project at Tactical Technology Collective. The rest of the time she is carrying out research for her PhD at Royal Holloway, University of London, on the use of personal data by charities and NGOs. She previously worked at Amnesty International, in digital communications, before undertaking her Masters in International Law.

Gary Wright is a researcher and project coordinator with Tactical Technology Collective with a history in technology & innovation in international development cooperation, as well as digital and privacy rights.

Stephanie Hankey is the co-founder and Executive Director of Tactical Tech and is currently a Visiting Industry Associate at the Oxford Internet Institute at the University of Oxford. Her work combines her background in technology, design and activism. She currently writes, consults and teaches on the politics of data and ethics in technology design.

A special thanks to Christy Lange for editorial support and Sasha Gubskaya for posting this piece online.

Published August 8, 2018.

Data and Elections in Chile: Update from Datos Protegidos

Digital Election Trends in Uganda

Personal Data and the Influence Industry in Nigerian Elections

Data & Politics Virtual Round-table: Sub-Saharan Africa Event Report

The Advent of Targeted Political Communication Outside the Scope of Disinformation in Ukraine

The Netherlands: Digital Literacy and Tactics in Dutch Politics

France: Data Violations in Recent Elections

Brazilian Elections and the Public-Private Data Trade

Catalonia: Contested Data and the Catalan Independence Referendum

USA: American Digital Politics and the Commercial Sector

Chile: Voter Rolls and Geo-targeting

India: Digital Platforms, Technologies and Data in the 2014 and 2019 Elections

Kenya: Data and Digital Election Campaigning

Colombia: Personal Data in the 2018 Legislative and Presidential Elections

Argentina: Digital Campaigns in the 2015 and 2017 Elections

Canada: Data Analytics in Canadian Elections

Mexico: How Data Influenced Mexico's 2018 Election

Malaysia: Voter Data in the 2018 Elections

Italy: Personal Data and Political Influence