| When Tactical Tech’s Data and Politics research team began to investigate how personal and individual data is being utilised in modern, digitally-enhanced political campaigns, we were quickly struck by the unbalanced coverage, particularly in the media, of the methods and strategies of data acquisition, analysis and utilisation by political campaigns across countries and different political contexts. In collaboration with international partners, we produced 14 studies to identify and examine some of the key aspects and trends in the use of data and digital strategies in recent and/or upcoming elections or referendums in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Italy, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, Spain – Catalonia, the United Kingdom and the United States. By working with journalists, digital rights advocates, lawyers, academics and data scientists, our multidisciplinary and practitioner-led approach has produced contextual overviews and tangible case studies of how personal and individual data is used by political campaigns in countries across the globe. With this collection of reports, we aim to expand our understanding of these issues beyond the contemporary, global-north focused coverage. |

|---|

In the wake of the Cambridge Analytica revelations, the connection between commercial practices and modern political advertising remains under-examined. Political advertising in the United States has adopted the same, proven strategies used to market and sell digital products. What’s more, these developments are not new; the commercial sector has long transformed the playbook of American politics, and the present, digital-first techniques powered by personal data are the latest such example. When viewed in this context, Cambridge Analytica’s endeavour to quantify, in the words of its ex-CEO, “the personality of every single adult in the United States of America” is not an exception. It is, instead, another example of commercial tactics incorporated into the American campaigning and electoral process with ripple effects around the globe. This U.S. case study explores the historical context of America’s digital-political marketing system, the growth of its digital marketing industry, and the democratic consequences of their convergence.

For this report, Tactical Tech partnered with Jeff Chester, Executive Director of the Center for Digital Democracy, and Kathryn Montgomery, Professor of Communication at American University. Both Chester and Montgomery have led consumer-rights initiatives and privacy legislation in the United States since the 1980s. A former investigative journalist, Chester co-directed the campaign that resulted in Congress creating the Independent Television Service for public TV in the 1980s and later co-founded the National Campaign for Freedom of Expression, an advocacy group supporting federal funding for independent artists. Named “Domestic Privacy Champion” by the Electronic Privacy Information Center in 2011, and honoured for his pioneering work by the Consumer Federation of America in 2017, Chester co-chairs the Transatlantic Consumer Dialogue’s Information Society group. Kathryn Montgomery, Ph.D. has published extensively on the role of media in society, spanning youth, advertising and marketing. She is the author of Target: Prime Time – Advocacy Groups and the Struggle over Entertainment Television (1989) and Generation Digital: Politics, Commerce, and Childhood in the Age of the Internet (2007). Her research and testimony have helped frame the national policy debate on a wide range of critical media topics. Among other achievements, she spearheaded a national campaign that led to the passage of COPPA (Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act) in 1998, the U.S. federal law to protect child privacy on the Internet.

Below is a selection of findings from Chester and Montgomery’s report, which spans the origins of modern digital campaigning, the integration of digital marketing in contemporary politics, and the implications of our data-driven political system. More details are available in the full report here.

Today’s digital political advertising ecosystem is shaped by a series of factors that have already influenced how digital products are sold and marketed. Now, these same forces are transforming elections

Chester and Montgomery identify three main factors that have enabled digital advertising to thrive in American politics: the broadcast/cable media industry’s commercial success with political advertising, a laissez faire approach to government regulation of political advertising removed from public accountability, and a business model built on the monetisation of user data.

A number of additional changes led to the growth of data-driven electioneering in American politics, beginning with the rise of political advertising in the 19th century and continuing through the 20th century, when TV advertising became a standard tool to influence voters.

Around the 2000 election cycle, campaigners used the internet for grassroots operations – engaging young voters, mobilising turnout and raising money – and not primarily for advertising. This practice changed dramatically over the course of the subsequent four presidential election cycles, as the effectiveness of online advertising improved with voter data and was leveraged by political campaigns. This evolution lagged slightly behind the general digital marketing business, which advanced to monitoring online behaviours and patterns.

Ad tech firms – including Facebook, Google and boutique companies – expanded into politics by developing “government” and “politics” verticals that catered specifically to the needs of political campaigns.

Compared to other countries, the United States has few restrictions on political advertising. The ineffectiveness of the Federal Election Commission, which oversees the use of money in political campaigns, exacerbates American political advertising’s lack of accountability.

The 2010 landmark Supreme Court case, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, concluded that the government cannot limit election spending by corporations, non-profit organisations, associations, labour unions, etc., thus ushering big money into elections and increasing the importance of political advertising in the process.

While these changes are distinctly American, they have manifested themselves around the world by way of the digital marketing industry’s focus on unrestrained, global growth – both via American companies operating abroad and by companies in other countries emulating American firms.

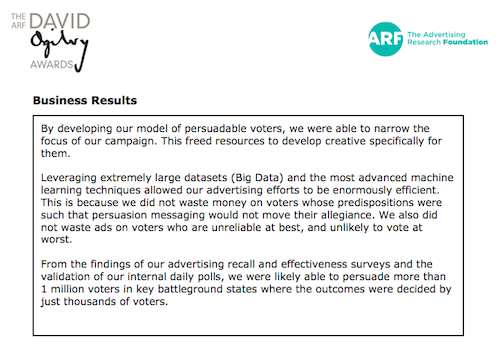

| A snapshot of digital marketing in the 2016 US elections • Digital tools were used by virtually all political groups (candidates, Political Action Committees - or PACs and special-interest groups) across the political spectrum (Democrats, Republicans, Libertarians) at both the state and national levels in the 2016 election cycle. • Chester and Montgomery identify six primary tools used by political campaigns in the US to engage and influence voters: voter data mining and profiling, mobile-based geotargeting, device tracking and “identity graph” construction, programmatic and micro-targeted advertising, personalised [TV](https://ourdataourselves.tacticaltech.org/posts/addressable-tv/) ads, and [emotion-based/psychological](https://ourdataourselves.tacticaltech.org/posts/psychometric-profiling/) analytics. • For example, the digital marketing firm Stirista claims to have matched 155 million voters to their “email addresses, online cookies, and social media handles.” Republican data firm Data Trust worked with Rocket Fuel, a programmatic advertising agency, to use its “moment scoring” application, which claims to use “artificial intelligence and massive big data architecture to identify influential moments, regardless of channel or device” allowing campaigns to “reach voters at their most receptive moments of influence.” • While much attention has been paid to the digital tactics of the Trump campaign, its overall digital strategy is emblematic of the way analytics and digital marketing are influencing politicking across political ideologies and transforming American notions of citizenship. In this emergent, data-intensive age, political campaigns are also becoming innovation hubs of their own. |

|---|

Major tech platforms not only executed campaign plans but were also actively involved in shaping larger campaign strategies

Based on recent research by other scholars, Chester and Montgomery submit that tech companies did not simply offer advertising services to campaigns but also provided calculated expertise. Companies deliberately organised staff to facilitate close, strategic relationships with campaigns. Employees working with Democratic campaigns, for example, generally had backgrounds in Democratic politics, and likewise for Republican campaigns. Interestingly, this staffing divide underscores the growing polarisation of American politics.

Technology companies introduced new ways of assessing their public engagement based on “demographics, behaviour, interest, and measures of attention,” catering to the strategic priorities, metrics and new forms of public engagement these firms helped form. Representatives from Facebook, Twitter and Google effectively served as digital consultants to campaigns, not just as advertising platforms.

The tactical relationships forged between companies and campaigns refutes the “neutral platform” claim made by several technology companies. These relationships were, ultimately, a result of the lucrative opportunities and downstream benefits that political campaigns offer technology companies. Tech companies considered campaigning work part of their larger lobbying efforts, recognising that successful political candidates would be key decision-makers regarding tech policy and regulation.

In response to such opportunities, Google, for example, established “micro-moments” based on search and mobile data, giving campaigners access to “micro-moments when undecided voters become decided voters...” According to Google, people posting videos on YouTube successfully shaped the political opinions of potential voters between 18 and 49 using these “micro-moments.”

Tech companies offered their services to both Democratic and Republican campaigns equally, but utilisation of this strategic advice varied widely.

In the words of Brad Parscale, the head of digital for Trump’s campaign, “Facebook and Twitter were the reason we won this thing.”

The merging of digital marketing and civic engagement underscores risks related to privacy, surveillance and voter suppression, all of which are repercussions of the digital marketing industry’s growth

Digital marketing tools have been adopted by virtually all major players in the US political system, not only campaigns. The expansion of the data brokering industry facilitates the construction of detailed profiles of nearly all American voters.

Chester and Montgomery argue that “the digital marketing industry has not been held sufficiently accountable for its use of race and ethnicity in data marketing products, and there is a need for much broader, industry-wide policies.” Voter profiles were used in at least three digital voter-suppression operations in the 2016 presidential race: one aimed at idealistic white liberals, one at young women and one at African Americans. Campaign operatives openly labelled these efforts as “voter suppression.”

The authors also state that “insufficient attention has been given to the broader core business objectives driving the industry’s global growth.” Exacerbating the problem, shrinking newsrooms are less equipped to hold political campaigns accountable. Moreover, media institutions face their own ethical dilemmas in critiquing digital marketing practices, as many of them leverage the industry’s programmatic advertising technologies.

US privacy regulation is much weaker than that of the European Union, where privacy is a fundamental right enshrined in law. The United States is one of few developed countries without a general privacy law. Thus far, private companies have skirted the Federal Trade Commission's efforts to protect consumer privacy online via “notice-and-choice” practices, in which changes are buried in privacy policies. Because political data is regarded as a protected form of free speech under The First Amendment, it has thus far been exempt from substantive regulation.

For more details on the above highlights, read the full report here.

An introduction to the Influence Industry project can be found at The Influence Industry: The Global Business of Using Your Data in Elections and an introduction to the tools and techniques of the political data industry can be found at Tools of the Influence Industry. Similar, country-specific studies on the uses of personal data in elections can be found here, with more to be added each week.

Varoon Bashyakarla is a data scientist and researcher at the Tactical Technology Collective. His past statistical undertakings led him to a variety of domains: public health, public safety, sports, finance, and cybersecurity. After working as a data scientist in Silicon Valley, he is now living in Berlin and exploring how personal information is used for political influence.

Special thanks to Stephanie Hankey and Christy Lange for their feedback and a big thank you to both Sasha Gubskaya and Safa Ghnaim for posting this piece online.

Published September 6, 2018.

Data and Elections in Chile: Update from Datos Protegidos

Digital Election Trends in Uganda

Personal Data and the Influence Industry in Nigerian Elections

Data & Politics Virtual Round-table: Sub-Saharan Africa Event Report

The Advent of Targeted Political Communication Outside the Scope of Disinformation in Ukraine

The Netherlands: Digital Literacy and Tactics in Dutch Politics

France: Data Violations in Recent Elections

Brazilian Elections and the Public-Private Data Trade

Catalonia: Contested Data and the Catalan Independence Referendum

Chile: Voter Rolls and Geo-targeting

India: Digital Platforms, Technologies and Data in the 2014 and 2019 Elections

United Kingdom: Data and Democracy in the UK

Kenya: Data and Digital Election Campaigning

Colombia: Personal Data in the 2018 Legislative and Presidential Elections

Argentina: Digital Campaigns in the 2015 and 2017 Elections

Canada: Data Analytics in Canadian Elections

Mexico: How Data Influenced Mexico's 2018 Election

Malaysia: Voter Data in the 2018 Elections

Italy: Personal Data and Political Influence