Our location reveals a wealth of information about us, not only about where we happen to be but also about what we are interested in, how we spend our time and what we value. It reveals our commutes to work, trips to the supermarket and outings with our friends and family. Political campaigns are recognising the value of this information and are investing in detailed, geolocation-based services for the intelligence they contain. Today, location information is the single most valuable piece of data for political campaigns. Instead of using demographics to target their political advertisements, campaigns are leveraging information about our habits and behaviours – insights offered by our geolocation data.

What is it?

Your location says a lot about you. Merely knowing which city you live in can suggest things about your political persuasion. So, too, can information about where you go. Your presence at a sports bar on a Friday night, for instance, may convey information about your attitude towards certain issues, which is valuable for modern campaigns pitching particular political platforms. By knowing where you stand, they can choose to ignore you or target you with specific messages.

Just as for-profit businesses have leveraged the insights of location data for marketing purposes, political campaigns are also catching on to the virtual necessity of doing so, particularly for their mobile audiences. While campaigns have long employed the digital marketing industry's basic geo-targeting techniques by treating swing and stronghold districts differently, advances in technology have enabled campaigns to target and track voters in new and more precise ways. Tactics commonly used to boost traffic and revenue for private companies have become standard tools of modern campaigns looking to sell their candidates.

Tactical Tech's research has identified a number of geolocation-related methods employed by political campaigns. This piece highlights three of them: geofencing, property and mobile geotargeting, and IP targeting. This list is far from exhaustive. Another emerging location-based political development – the use of personal data in door-to-door campaigning – will be covered in a forthcoming piece in our series.

Where is it being used?

Most of the cases identified here are from the United States or exports from the US, as this body of evidence is well-documented. In truth, the use of geotargeting in political campaigning is not an exclusively American phenomenon. Some form of geo-specific micro-targeting is taking place in virtually every election campaign with basic resources around the world; nearly all campaigns use popular tech platforms to geotarget advertisements, whether on the city, district, neighbourhood or individual household level. As large tech platforms make geotargeting tools more accessible and less expensive, even sophisticated practices will probably be adopted more widely in the future. Geofencing technologies and IP targeting, as explained below, have been employed extensively in the United States, though the technical infrastructure to employ them elsewhere already exists.

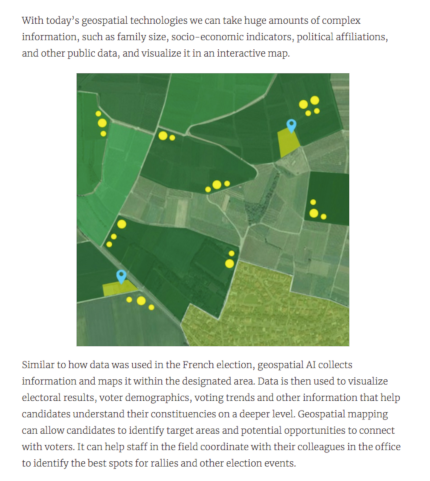

Other advanced forms of geographic micro-targeting have been documented in Spain and several Latin American countries. Cloud Factory, a company based in Milan, partnered with Paris-based digital consultancy Liegey Muller Pons to refine data used by Emmanuel Macron's 2017 presidential campaign.

How does it work?

A Selection of Geotargeted Ads

Geofencing

In April 2016, United States Senator Lisa Murkowski was seeking reelection in Alaska and her campaign promoted the ad below online. The ad declares Murkowski's support for building an 11-mile road through Izembek National Wildlife Refuge for medical emergencies, a project that both her rival and the Department of the Interior (the federal agency that oversees national parks) opposed at the time.

In addition to sharing the ad on Facebook, Murkowski's campaign also directed it to Washington D.C. Specifically, the ad was targeted to the Interior Department's headquarters (1849 C Street, NW), mere blocks from the White House at lunchtime, but not outside of the building. Department of the Interior officials, browsing their newsfeeds at lunch, saw the ad appear 7,000 times.

After winning her reelection campaign in 2016, Murkowski spearheaded the effort to build the road, which was formally approved in January 2018 by Ryan Zinke, Secretary of the Interior.

While technically undisclosed, the mechanism behind Murkowski's selective targeting of the Interior Department was likely a geofence. Geofences are virtual perimeters around a point of interest. When a location-enabled device like a mobile phone enters an enclosed area – which can range from a single store to an area with a several-mile radius – it triggers desired actions (e.g., ad displays). The purpose of a geofence is to target your content to a defined area of interest and nowhere else.

This is exactly the tactic Michelle Bachmann employed in 2010, when she ran against Tarryl Clark for a Congressional representative seat in Minnesota. Bachmann's team attacked Clark for supporting taxes on popular American snacks and beverages including beer, corndogs and bacon. The ad was originally planned to air on television during the Minnesota State Fair. Eric Frenchman, a strategist who helped reelect Bachmann and works for an online political ad agency, however, devised a plan to display the ad directly to voters while they were at the fair. His team did this by uploading the ad to YouTube and geotargeting it to mobile devices within a 10-kilometre radius of the fair.1

Other politicians have used geofences in the past as well. Thinknear, a location specialist in mobile advertising, published a guide on "How political candidates can influence voters through mobile ads." The guide describes how in the 2012 election cycle, Mitt Romney's presidential campaign geofenced a concert in Grant Park in Chicago because the audience's demographics appeared pro-Romney. In May 2015, Ted Cruz's campaign geofenced the Venetian hotel in Las Vegas during the Republican Jewish Coalition to promote his pro-Israel stance to attendees.

Property and Mobile Geotargeting

In addition to geofencing, a number of other geo-specific strategies have been widely adopted in political campaigning. While geofencing isolates very specific areas of interest, targeting larger geographic units has long been standard practice. In 2012, with the help of mobile-ad company Jumptap, Mitt Romney's campaign rolled out mobile ads like the one below in ZIP codes believed to be reliably pro-Romney – and not, presumably, to mixed Obama-Romney districts, even if Romney voters lived there.

Also in 2012, Vincent Harris – now CEO of Harris Media, a company that has serviced far-right nationalist parties like Alternativ für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany – geotargeted nine Christian colleges with mobile ads tailored to each university's colours and mascots on behalf of Rick Perry's 2012 presidential race.

These applications of location data have had multiple effects. First, companies that advertise their location-based technologies specifically for political campaigns have proliferated. Additionally, location data-collecting companies that traditionally operate outside of politics have found new customers among political campaigns eager to use the location data they've amassed.

One such example is Outra, a UK-based startup founded by Lynton Crosby – an Australian political strategist who helped elect Boris Johnson as London's mayor in 2008 and Prime Minister David Cameron in 2015 – and Jim Messina, an American strategist with a range of international political engagements including Cameron's campaign in the UK and Barack Obama's 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns. Outra specialises in residential property data, with 10% of the company's business coming from political campaigning. According to their website, "Profiling all UK residential property allows you to match and profile customers and prospects to the address (property) level..."

In addition to companies creating services to meet campaigns' demands, outsiders have joined the political data ecosystem. The Weather Channel app, for example, ingests ZIP code data in order to serve forecasts to its users. In 2012, The Weather Channel Companies announced a partnership with Jumptap (the same company involved in delivering the Romney mobile ad above) for national election advertising.

Our hyper-local context and targeting ability, down to the ZIP code level, offers political advertisers access to The Weather Channel’s local ‘sweet spot,’ putting them right in front of the voters they’re trying to reach. That access, combined with Jumptap's political expertise, makes The Weather Channel mobile properties a must-have for anyone launching a major political campaign. – Patrick McCormack, VP of Mobile Sales & Strategy at The Weather Channel Companies

Alluding to the value of connecting political campaigns to their valuable location data, McCormack stated, "We think the revenue opportunity is significant — we’re bullish on it because we know that the mobile phone is the optimal way to reach people anytime, anywhere and certainly when they’re out to vote."

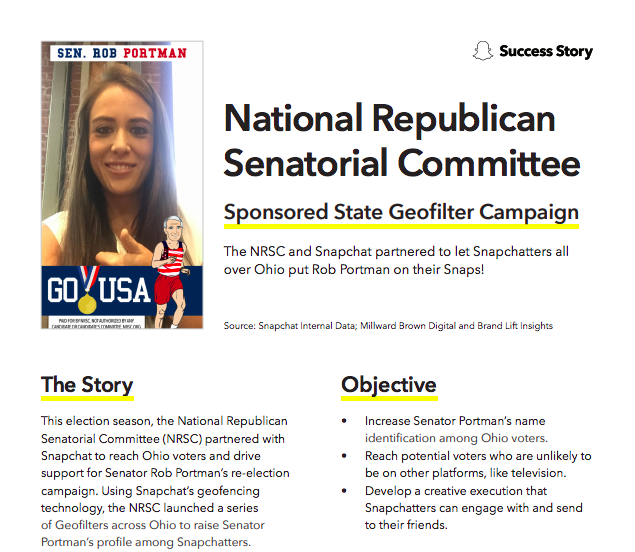

Another example is Snapchat, a company that does not specifically cater to political work but whose location data has been leveraged by a variety of political campaigns. In the UK's 2017 snap election, which resulted in a surprise Labour comeback, for instance, Snapchat was used to encourage young people to vote via a tool in which they could look up their voting location. The message was viewed 7.3 million times and 780,000 people used the tool to look up their polling place.

As a final example, New York City-based location intelligence company Ubimo spun up a political services division, claiming that their services circumvent many of the assumptions undermining standard offerings.

Mapping historical voting data to correspond with local data is a world first. Previously campaigns had to rely on virtual profiles and audience segments for any mobile targeting. This involves assumptions such as ‘visitors to a Democratic candidate’s website are Democrat voters’ or ‘audiences reading an article about a Republican policy, must be Republican’. These kinds of assumptions are inaccurate at best. We don’t deal in assumptions, rather we’re giving campaigns the ability to tap actual voting data at a very granular geo level, which is completely unprecedented. – Ran Ben-Yair, Ubimo CEO

IP Targeting

In addition to geofencing and property/mobile geotargeting, political campaigns have also adopted IP targeting. The Obama campaign, for example, used geolocation information ascertained from IP addresses to deliver ads to districts believed to be strongly Democratic and demographically suitable for the campaign. More recently, DS Political, a political consultancy based in Washington D.C., used IP and cookie targeting to serve 8 million digital video impressions to 450,000 voters in the 2015 Canadian Federal elections. The company claims that its campaigns were so successful that it has since been involved with two provincial Canadian elections. The Liberal Democrats in the UK used the company Digital Element, branded as "the global IP geolocation leader", in the 2015 general election.

How is your data used?

At the very least, geotargeted ads require access to a user's location, whether in the form of a city, home address or exact GPS coordinates of a mobile phone.

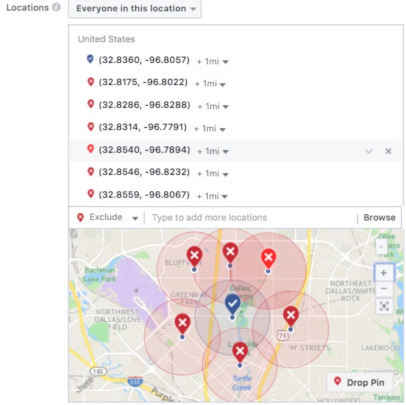

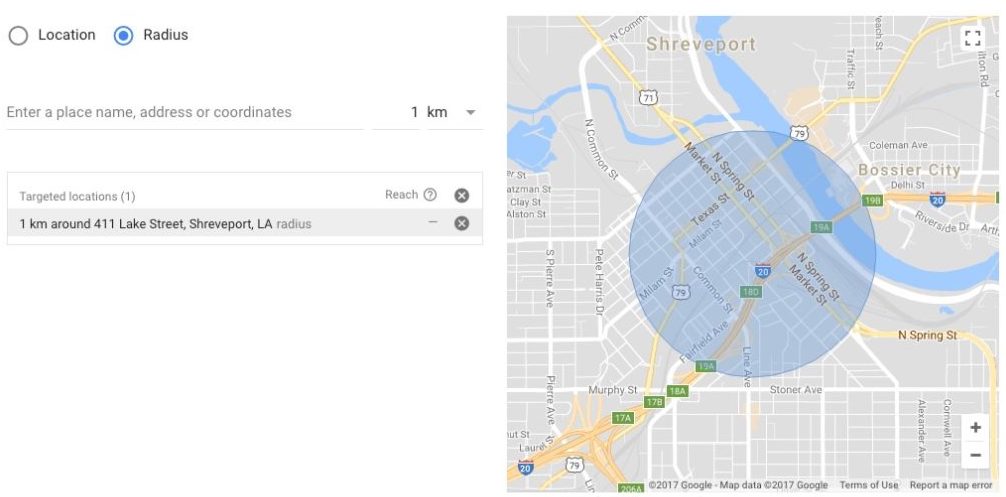

Facebook and Google's advertising platforms are used extensively by political campaigns around the world, and their advertising interfaces make geotargeting ads extremely easy; a highly geotargeted ad can be launched within a matter of minutes and both services support geofencing technology. Location information is based on self-reported information (e.g., city of residence) and connection information (e.g., GPS coordinates when accessing the service). Their services enable advertisers to target whole countries or very granular regions in combination with demographics. Google AdWords' "Proximity Marketing" even uses Bluetooth and Wi-Fi to reach users physically in a pre-specified location in realtime.

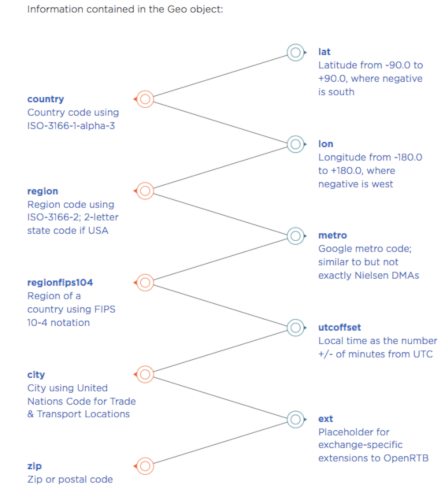

A variety of geographic information can be relayed in the "geo object," the container for information about a connected device's physical location.

In addition to the examples cited above, geofences have also been used around polling locations in the US. As reported in The New Disruptors, Jim Walsh, founder of political consultancy DS Political, noted:

There's lots of geo-fencing opportunities. We discovered in this last cycle, where you could actually geofence a polling location and serve ads to every single person who's waiting in line to vote that day. How fantastic! We actually called it..."The Last Word" because it was the actual last opportunity someone had to see an advertisement before they voted.

Putting all of these elements together, the graphic below shows the process of serving an ad to a voter in the "Last Word" scenario Walsh described.

Even when a geofence does not deliver an ad to a user, the presence of the user in the geofence can still be recorded. In other words, if political strategists wanted to store device IDs of attendees at a political event and paint a more complete picture of the attendees with behavioural data for future targeting purposes, they can do so. In fact, this is exactly what happened at the 2016 Republican and Democratic national conventions in the US, which were both geofenced, enabling campaigners to harvest attendees' data, according to a digital marketer.

The campaigns and the media tents were able to collect the audience on WiFi and then target specific campaign messages within that radius [...] We can cultivate them even if the user doesn’t perform an action – one just has to target messages within proximity. Once you start the conversation, you will have time post-conference or political convention to still get them! – Allie Vadas, Director at Jellyfish

Christopher Yatrakis, Head of Mobile Business Development at digital marketing firm Factual, expressed similar sentiments. The company's "Geopulse" suite caters to the needs of political campaigns. In an interview about one of the company's partnerships, Yatrakis said that Factual "can give campaigns the ability to look back in time and create a Tailored Location Segment of users that attended the opponent’s campaign rallies. Campaign managers can target event attendees in real-time to help combat the opposition’s attacks and bolster support for their candidate." The firm curates data on 90 million "points of interest" around the planet, including city halls, parks and local businesses and even collects data on environmental factors like air quality for marketing purposes.

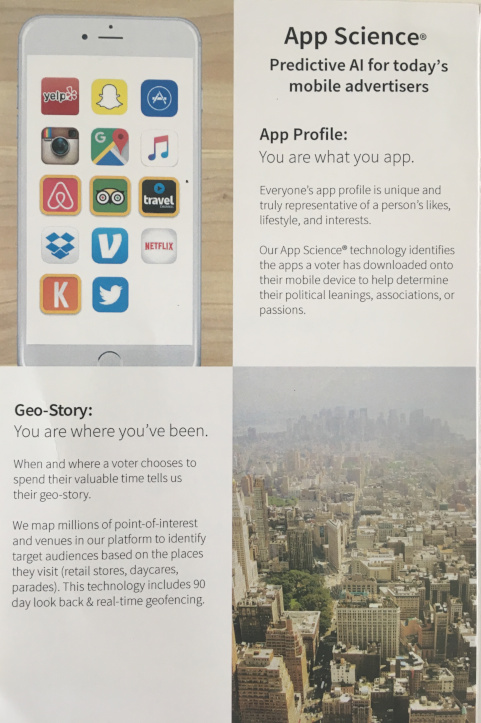

Sabio Mobile is an American mobile advertising company based in LA that combines information about users' geolocation with their phones' app ecosystem to infer customers' past, present and future consumption preferences. The firm offers 90-day look-back and real-time geofencing support and has also marketed its services to capture growing demand from political campaigns.

Case Study: El Toro

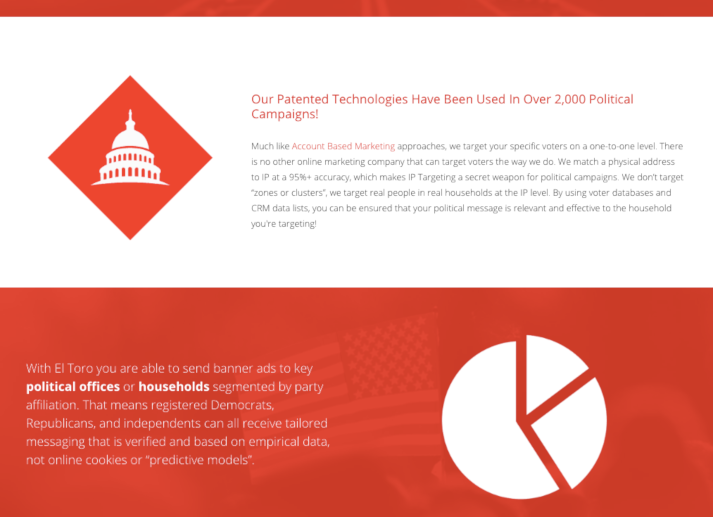

In Guyana in 2015, El Toro, an American ad tech company based in Kentucky, helped opposition presidential candidate David Granger end the left-wing incumbent People’s Progressive Party rule. The victory was particularly notable because the Guyanese government controlled TV and radio, rendering them unusable for the opposition candidate. The firm's IP-targeting technology aimed at young voters circumvented the government-controlled media.

As Insider Louisville reported reported, "More than 60 percent of Guyanese have Internet-connected mobile devices, so El Toro helped the Granger campaign become more digitally savvy using patent-pending technology to map household IP addresses, allowing the campaign to target individuals or groups based on location." Brad Goodman, an American political consultant for Granger, affirmed, "By using El Toro, we were able to target voters on a granular level with the right messages at the right time."

This marketing video from 2016 sheds light on the scope of El Toro's IP targeting technology.

El Toro's CEO Stacy Griggs stated in an interview, "We've mapped about 140M US households to an IP address, and we can place ads in front of those people based off of their IP address."

The company claims to be the first ad tech company to offer a money-back guarantee based on results. For campaigns spending over $100,000, failure to increase voter turnout rates among targeted voters entitles campaigns to up to a 50% refund.

One of El Toro's latest features, "reverse append," gives clients looking to influence users online the ability to target them in the offline world as well. A video overview of the feature from August 2017 is below.

In fact, El Toro devoted a full section of its website to its political clientele. The screenshots below, taken directly from the website, feature the breadth and depth of the company's political services.

Though experts debate the effectiveness of IP targeting, El Toro and companies offering similar services do not seem to suffer from any shortage of political clients.

Case Study: L2

L2, an American voter data firm that specialises in collecting and curating data for campaigns, also offers a range of location-based services. Its website doesn't name clients, but indicates that Super PACs, consultants, unions, campaigns large and small, and analytics companies are among them. One of its premier products, VoterMapping, offers clients the ability to analyse and aggregate voter attitudes over a customisable geographic area.

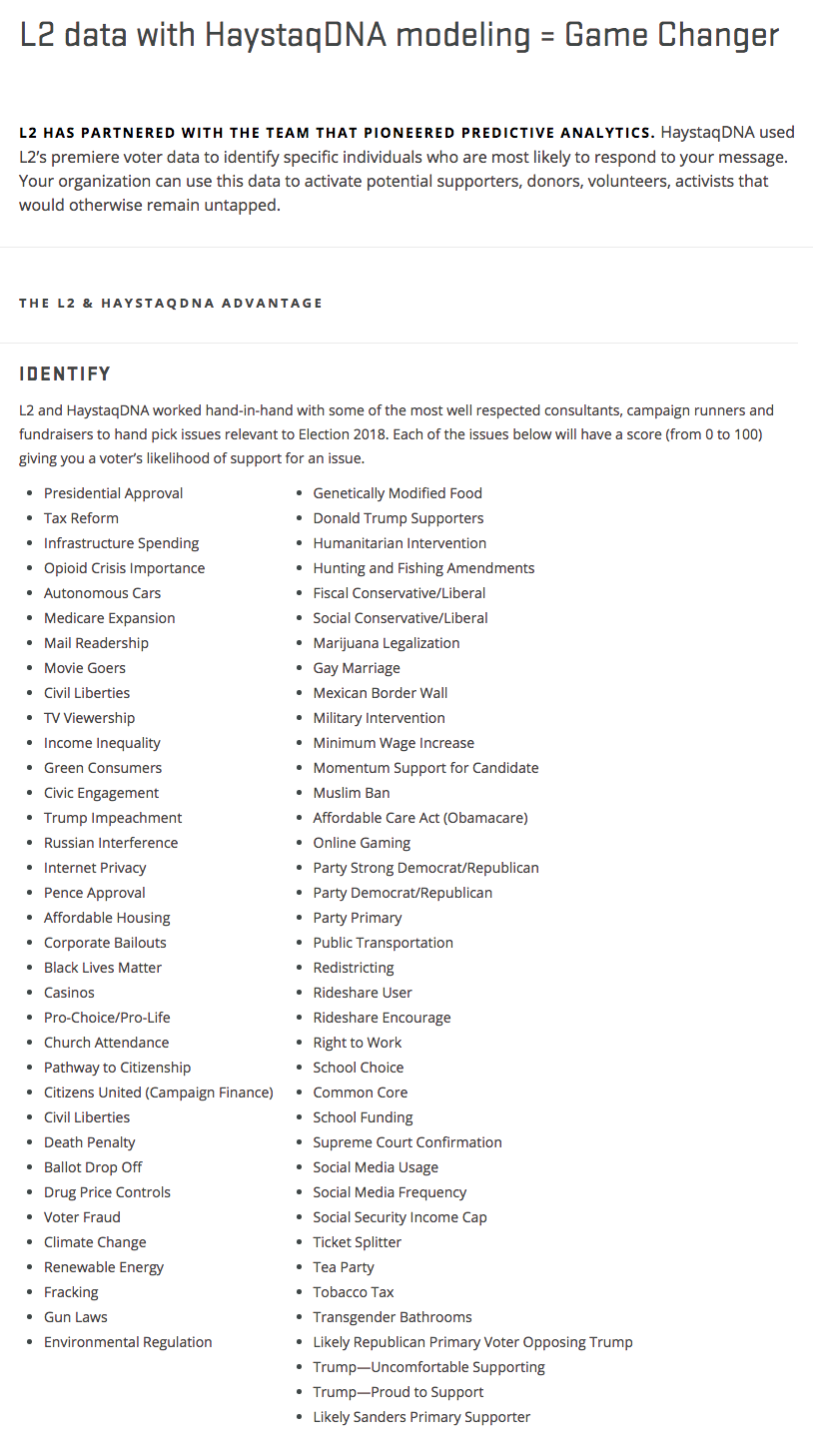

Like El Toro, L2 also offers IP targeting. In this case, L2 partnered with third-party specialists in predictive modelling to provide estimates on how voters score (between 0 and 100) on a variety of salient political issues. For political campaigners, information on voters' stances on different issues is valuable for crafting messaging and tailoring advertising campaigns.

Is it new?

Broad-based geographic targeting – for example, special treatment of swing districts – is not a new practice. Political campaigns have a long history of tailoring their messages to their various audiences. Early on, mailers and direct contact with voters provided campaigns such means. In the 1980s, campaigns geotargeted ads to districts whose voting preferences could be predicted easily. However, because the political leanings of individual voters in those districts were unknown, messages were usually limited to "get out the vote" campaigns.

IP targeting and geofencing for political campaigns are more recent developments. Geofencing in the form explained here was not possible until the past decade or so, until apps on smartphones connected to GPS. IP targeting did not gain traction with politicians until about 2012, though it had been used previously. Today, political campaigns are no longer constrained by a lack of information about individual political preferences.

Why should we care?

The use of geolocation data in political campaigning should give us pause on multiple fronts. Our geolocation data reflects our habits, behaviours and preferences, and for this reason, it is the single most valuable piece of information for political campaigns interested in learning about you, which – they claim – allows them to target you more effectively.

Our geolocation data is sensitive but also available from a variety of sources: gleaned off the open exchange and added to bid requests, stored directly by location-enabled services, accessed via APIs that connect to apps with location data, licensed from third-party providers and purchased directly from a data broker. And not only is this information available from many sources, but the volume of data being collected is also increasing. According to Proxbook, a proximity sensor research provider, the number of physical location sensors around the world is increasing substantially.

Our geolocation data can be imagined as troves of dots moving around on maps between work, home, the subway, a friend's house, a concert, the park, home again. On its own, this information is more or less meaningless. Its value comes from the assumptions made about it and the interpretations applied to it.

We generally don't think of our location data as inputs to political profiles constructed about us. These profiles are not transparent, and unsurprisingly, most people are unaware of geolocation-based practices, even if they benefit from their commercial applications. If you have ever landed in an airport, turned on your phone and received a notification from a service like Uber about hailing a ride from the airport, it's because the airport was geofenced.

Such commercial, geolocation services are fundamentally different from those built by political campaigns. Campaigns' use of geotargeting services invites them to select whom to include and whom to exclude, exacerbating the risk of excluding certain groups from the democratic process altogether. Some services have already showcased their successes by publishing "high-value areas", leading some to wonder how these services have treated "low-value" areas. Other firms advertise their ability to custom-target geographies of interest in order to deliberately exclude others.

What's more, there's already evidence of geolocation techniques being misused in political contexts. As one example, journalists and technologists have exposed evidence that women visiting abortion clinics in several American cities (including New York City, St. Louis and Pittsburgh) have been targeted with geofenced advertisements from anti-abortion activists. Even though this advertising campaign isn't tied to a political candidate, it is political, built on commercial infrastructure and extends beyond traditional party politics. In particular, it calls into question how geotargeting technologies can undermine matters of political participation more broadly, especially when used towards ethically dubious ends.2

Varoon Bashyakarla is a data scientist and researcher at the Tactical Technology Collective. His past statistical undertakings led him to a variety of domains: public health, public safety, sports, finance, and cybersecurity. After working as a data scientist in Silicon Valley, he is now living in Berlin and exploring how personal information is used for political influence.

1 Geofencing in the private sector is commonly paired with geoconquesting, a tool to lure customers away from rival businesses. For example, a coffee shop may geofence a competitor across the street and send special deals via banner ads or push notifications to customers in the vicinity of their competitor in hopes of luring them away from the competition. Massachusetts-based Dunkin' Donuts has employed such strategies to take market share away from Starbucks. ↩

2 In a similar though less political vein, evidence that law firms are sending ads to patients in emergency rooms has also been documented. ↩

A big thank you to Stephanie Hankey and Christy Lange for their suggestions on drafts of this piece. Sasha Gubskaya also offered comments on the text, and both she and Safa Ghnaim helped post it online.

Published September 11, 2018.

Gwajin A/B: Gwaje-gwaje wajen tura sakonnin yakin neman zabe

التلفزيون الموجه: من يشاهد ما تشاهده؟

Akwatin Talabijin mai jin magana: Wa ke kallon abinda kake kallo?

Keta hurumi, Fallasa, da Kutse: Yadda rayuwar bayanan mai zabe ke cikin hadari

Manhajojin jirgin yakin neman zabe: Danna ka yi musharaka

អេបយុទ្ធនាការឃោសនា៖ ចុចដើម្បីចូលរួម

بيانات المستهلكين: وقود الحملات الرقمية

Bayanan mutane: Makamashin wutar yakin neman zabe a kafafen zamani

Dados Pessoais: Persuasão Política. Dentro da Indústria da Influência. Como funciona.

Datos Personales: Persuasión Política. Cómo funciona la Industria de la Influencia desde Adentro.

Sauraron bayanai a kafafen zamani: Daga dandalin sada zumunta

الاستهداف الجغرافي: القيمة السياسية لأماكن وجودك

Isa ga mutum ta inda yake: Amfanin wuraren da kake zuwa don manufar siyasa

البيانات الشخصية: عملية الإقناع السياسي

Bayanan mutane: Amfani da su wajen janyo ra’ayin siyasar mutane

Личные данные: политические убеждения. Внутри индустрии влияния

Особисті дані: політичне переконання. Всередині галузі впливу

التصنيف النفسي: الإقناع حسب الشخصية

Amfani da ayyukan mutum wajen kiyasin dabi’arsa: Janyo hankalin mutum ta dabi’arsa

Kiran wayan da tura sakonnin mutum-mutumi: Yakin neman zaben ta na’urar yi da kanka

تأثير نتائج البحث: الوصول إلى الناخبين الباحثين عن إجابات

Tasiri wajen amsoshi yayinda kake bincike: Isa ga masu kada kuri’a a zabe masu tambayoyi

Bibiya daga wani na-gefe: Kukis, Bikons, zanen yatsu da sauransu

Fasahohi masu tasowa: Abubuwan da zasu jagoranci fasahar yakin neman zabe

Kundin masu zabe: Bayanan siyasa a game da kai

ទិន្នន័យផ្ទាល់ខ្លួន៖ ការបញ្ចុះបញ្ចូលផ្នែកនយោបាយ ឥទ្ធិពល និងដំណើរការនៅក្នុងឧស្សាហកម្មនេះ មានជាភាសាខ្មែរ

Now Translated - Personal Data: Political Persuasion. Inside the Influence Industry

Tools of the Influence Industry

ទិន្នន័យអ្នកប្រើប្រាស់៖ ការបង្កើតឲ្យមានយុទ្ធនាការឃោសនាតាមបែបឌីជីថល

Dados de Consumidor: O combustível de campanhas digitais

Consumer Data: The fuel of digital campaigns

Datos de consumo: El combustible de las campañas digitales

سجلات الناخبين:بيانات سياسية عنك

Ficheros de votantes: Información política sobre ti

បញ្ជីអ្នកបោះឆ្នោត៖ ទិន្នន័យនយោបាយអំពីអ្នក

Arquivos de eleitores: dados políticos sobre você

Voter Files: Political data about you

خروقات وتسريبات واختراقات: حياة بيانات الناخبين المخترقة

Brechas, Filtraciones y Hackeos: La vulnerabilidad de los datos sobre votantes

ការរំលោភបំពាន, ការលេចធ្លាយ និង ការលួចយកទិន្នន័យ៖ ភាពប្រឈមនឹងគ្រោះថ្នាក់នៃទិន្នន័យរបស់អ្នកបោះឆ្នោត

Violações, Vazamentos e Hacks: A vida vulnerável dos dados dos eleitores.

Breaches, Leaks and Hacks: The vulnerable life of voter data

اختبار أ/ب: تجارب على رسائل الحملات

Pruebas A/B: Experimentar con mensajes de campaña

ការធ្វើតេស្ត A/B៖ ពិសោធន៍ក្នុងយុទ្ធនាការផ្ញើសារ

Testes A/B: Experimentos em mensagens de campanha

A/B Testing: Experiments in campaign messaging

تطبيقات الحملات: انقر للمشاركة

Apps de Campañas: Pulsa aquí para participar

Aplicativos de Campanha: Toque para participar

Campaign Apps: Tap to Participate

تقنيات الطرف الثالث للتتبع: ملفات تعريف الارتباط وأجهزة الإرشاد وبصمات المتصفح وغيرها

Rastreo de terceros: cookies, balizas, huellas y más

ការតាមដានពីភាគីទីបី៖ ឃុគឃី, ប៊ីខិន, ការស្គេនស្នាមក្រយ៉ៅដៃ និងវិធីសាស្ត្រជាច្រើនផ្សេងទៀត

Rastreamento de terceiros: cookies, beacons, impressões digitais e muito mais

Third-Party Tracking: Cookies, beacons, fingerprints and more

الاستماع الرقمي: الاطلاع على شبكات التواصل الاجتماعي

Escucha Digital: Perspectivas sobre las plataformas de redes sociales

ការស្តាប់តាមឌីជីថល៖ គំនិតដកស្រង់ចេញពីបណ្តាញសង្គម

Escuta Digital: Informações das Redes Socias

Digital Listening: Insights from social media

Geo-targeting: el valor político de tu ubicación

ការកំនត់គោលដៅទីតាំងភូមិសាស្រ្ត៖ គុណតម្លៃផ្នែកនយោបាយនៃទីតាំងរបស់អ្នក

Direcionamento por Geolocalização: O valor político da sua localização.

La influencia de los resultados de búsqueda: acceder a votantes en busca de respuestas

ឥទ្ធិពលតាមរយៈលទ្ធផលនៃការស្វែងរក៖ ឆ្ពោះទៅដល់អ្នកបោះឆ្នោត ដើម្បីស្វែងរកចម្លើយ

Influência do resultado de buscas: Alcançar eleitores que procuram respostas

Search Result Influence: Reaching voters seeking answers

Televisión Dirigida: ¿Quién está viendo lo que ves?

ទូរទស្សន៍ដែលអាចប្រាស្រ័យបាន (Addressable TV)៖ នរណាកំពុងមើលនូវអ្វីដែលអ្នកកំពុងមើល?

TV Endereçável: Seus Hábitos de Visualização como Ativos Políticos

Addressable TV: Your Viewing Habits as Political Assets

المكالمات الهاتفية الآلية ورسائل المحمول النصية: الحملات الدعائية المميكنة

Llamadas Automáticas y Mensajes Celulares: Difusión de campaña automatizada

ទូរស័ព្ទស្វ័យប្រវត្តិ និងការផ្ញើរសារតាមទូរស័ព្ទ៖ ការធ្វើយុទ្ធនាការផ្សព្វផ្សាយដោយស្វ័យប្រវត្តិ

Telefonemas Automáticos e Mensagens Celulares: Divulgação automatizada de campanha

Robocalls and Mobile Texting: Automated campaign outreach

WhatsApp: The Widespread Use of WhatsApp in Political Campaigning in the Global South

Perfiles Psicométricos: Persuasión basada en personalidades

ទម្រង់ចិត្តវិមាត្រ៖ ការបញ្ចុះបញ្ចូលតាមរយៈបុគ្គលិកលក្ខណៈ

Perfil Psicométrico: Persuasão pela Personalidade nas Eleições

Psychometric Profiling: Persuasion by Personality in Elections

التقنيات المستقبلية: آفاق جديدة في تكنولوجيا الحملات

Tecnologías Emergentes: La próxima frontera en las tecnologías de campaña

បច្ចេកវិទ្យានៅថ្ងៃអនាគត៖ វិធីសាស្ត្រនាពេលអនាគតក្នុងបច្ចេកវិទ្យាយុទ្ធនាការឃោសនា

Tecnologias Futuras: A Próxima Fronteira nas Tecnologias de Campanha

Upcoming Technologies: The next frontier in campaign technology

Behavioral Data in Elections: Video